Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has transformed many fields, especially education and research, with advances in natural language processing (NLP) and large language models (LLMs) expanding their use and understanding (Alqahtani et al., 2023). This impact is most evident in AI’s influence on educational practices. AI has become a powerful tool in education, reshaping writing instruction as it is increasingly integrated into higher education contexts such as language learning (Romero et al., 2024). Opinion essays, a common form of academic writing at university, help students develop critical thinking by stating a stance, supporting it with evidence, and organizing ideas using structures such as cause-effect or compare-contrast (Gordon, 1990;Setyowati, 2016). The easy availability of online essay samples (Setyowati, 2016) and AI-generated responses has raised concerns about originality and authorship, highlighting the need to teach students responsible, informed use of generative AI throughout the writing process. Rather than generating full essays, students can use AI more constructively for outlining or receiving feedback to support learning. AI-enabled learning systems, such as adaptive platforms and Automated Writing Evaluation (AWE) tools, provide immediate, personalized feedback, supporting revisions and helping students refine their work over time (Akyüz, 2020; Hung et al., 2024;Kabudiet al., 2021). AI tools such as ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot support brainstorming, idea organization, and revision, yet research shows notable limitations in their use for writing instruction. Bibliometric and systematic analyses show most studies focus on single tools in narrow settings, with ChatGPT-4 dominating the literature while Gemini and Copilot remain underrepresented (Frumin et al., 2025;Kabudiet al., 2021). This highlights the need for research on a broader range of generative AI tools. Literature reviews note a gap in comparative studies on the educational impact of different platforms across diverse learners and writing tasks (Alqahtani et al., 2023;Kabudiet al., 2021). Furthermore, the needs of EFL students who are transitioning from paragraph to essay writing remain underexplored. This study addresses this gap by comparing three generative AI tools in supporting students through key stages of the writing process. Evaluating students’ experiences in a state university preparatory program in Ankara offers insights for educators supporting learners at this transitional proficiency level. To this end, the study examines how B+ level EFL students use three generative AI tools in the key stages of essay writing and addresses the following research questions:

1.How do B+ level EFL students’ perceptions of effectiveness differ across ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot in supporting the stages of opinion essay writing (brainstorming, outlining, and feedback)?

2.What qualitative experiences and perceptions do B+ level students report about the strengths and limitations of these tools in supporting their writing?

3.How does working with these tools influence students’ attitudes toward future AI use for writing support?

Literature Review

Generative AI in Education

Artificial intelligence (AI) has garnered significant public interest, particularly following the release of large language models (LLMs) and chatbots such as ChatGPT, Copilot, and Gemini, which enable users to interact directly with LLMs (Barrett & Pack, 2023; Lin, 2023). Lin’s (2023) review of major AI developments clearly explains the rapid pace and broad scale at which generative AI tools like ChatGPT, Gemini, and Copilot have entered mainstream use. These tools, trained on vast natural language data, can generate original and contextually appropriate responses in ways that echo how humans produce novel language based on limited input. This ability reflects principles of generative grammar (Chomsky, 1991). While the technology is impressive, using these tools in education demands more than technical skill. Educators must make them accessible and ensure ethical, pedagogically sound use. This is crucial in language education, where writing requires complex skills like organizing ideas, developing arguments, and revising for clarity. Unlike receptive skills, writing involves active production, complicating AI integration. Barrett and Pack (2023) found that students and teachers generally accept generative AI for early writing stages like brainstorming and outlining but worry about its use for full-text production. These findings highlight the need to understand how these tools are used and perceived by educators and learners. Recent studies also highlight how intelligent technologies enhance personalized learning and support creativity for learners and teachers (Urmeneta & Romero, 2024; Yan et al., 2024). AI has become a disruptive force in education, enabling hybrid intelligence and transforming practices such as essay writing and feedback (Järvelä et al., 2023). In language education specifically, AI is becoming a key component in supporting teaching and learning (T. L. Nguyen et al., 2024). Individuals can now generate writing instantly on almost any topic by using simple prompts. Generative AI tools have become indispensable aids for students. AI-powered tools provide timely, automated feedback that not only addresses surface-level issues such as grammar, punctuation, and spelling but also enhances complex aspects of writing, such as content development, argumentation, and coherence. By providing grammar and style suggestions, these tools enhance students’ linguistic accuracy and allow educators to concentrate on higher-order writing skills. This makes AI tools an efficient and scalable alternative to traditional teacher feedback (Gayed et al., 2022; Link et al., 2022; Malik et al., 2023). In this context, generative AI is both a source of inspiration and a practical support tool in the writing process.

AI-Assisted Writing and Its Pedagogical Benefits

Writing, a productive skill, is particularly challenging due to its high cognitive demands. Unlike receptive skills such as listening or reading, which involve comprehension, it requires generating ideas, organizing thoughts, and applying grammar and vocabulary (Taskiran &Goksel, 2022). At the higher education level, it requires a systematic approach to exploring and organizing ideas and demonstrating critical thinking to support the writer’s perspective (Bailey, 2014). This process follows a structured format of introduction, body, and conclusion, each serving a specific function in presenting the thesis, developing arguments, and summarizing key points (Biber et al., 2004; Cumming et al., 2000). As students plan, draft, and revise, they are expected to move beyond grammar, focusing on organization, mechanics, and cohesion to produce effective writing (Mukminin, 2012). Given the complexity of these tasks, which require clarity, precision, and critical engagement with ideas (Paltridge & Starfield, 2016), writing can be time-consuming and mentally demanding (Flower & Hayes, 1981; Graham &Sandmel, 2011). Building on AI’s role as a supportive writing tool, many educators integrate it into classrooms for grammar correction, content development, personalized feedback, and to boost writing confidence and motivation. AI tools are already popular among EFL users. The pedagogical impact of generative AI in writing instruction is particularly relevant from constructivist and sociocultural perspectives. Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development highlights the need for appropriate tools and support to help learners reach their potential. AI tools can serve as supportive peers or scaffolding, providing immediate, ongoing feedback that personalizes learning and fosters self-regulation (Dizon & Gold, 2023; Fong & Schallert, 2023).Zaiarnaet al. (2024) observed that EFL instructors increasingly use AI tools like ChatGPT and Gemini in classrooms, recognizing their potential for instruction and assessment. Xu et al. (2024) reported that EFL students using ChatGPT improved coherence and organization after multiple rounds of AI feedback. AI tools are also described as transformative in EFL settings, supporting grammar, outlining, and content development (Godwin-Jones, 2022). Studies also show measurable improvements in students’ writing quality and organization with such tools (Malik et al., 2023; Marzuki et al., 2023). AI tools also offer personalized feedback that promotes learner autonomy. Moreover, they can provide immediate, individualized feedback, sometimes more readable and detailed than instructor feedback. They can suggest alternative expressions, improve readability, and generate new topic ideas to support revision. Research shows that automated feedback can improve students’ writing, especially with multiple rounds of revision (Huang & Wilson, 2021;Mushthozaet al., 2023). Beyond this, AI writing tools can boost student confidence and reduce anxiety by offering accessible help during the writing process. As writing is often emotionally demanding, such tools can enhance motivation and encourage learner independence. These effects are important given that writing is shaped not only by cognitive demands but also by the writer’s emotional and motivational experiences (Bruning & Horn, 2000; Dizon & Gold, 2023; Fong & Schallert, 2023; Ghafouri, 2024; Graham, 2018).

Concerns and Limitations in AI-Assisted Writing

Despite their benefits, AI tools in writing instruction raise concerns about academic integrity, over-reliance on technology, reduced creativity, and unequal access. This study acknowledges that a balanced view is crucial, and the integration of AI must be carefully structured to account for these pedagogical, ethical, and affective dimensions (Dehouche, 2021; Iskender, 2023). A key concern is academic integrity and educators question the originality of AI-generated content. Over-reliance may encourage shortcuts, undermining the purpose of academic writing and honest self-expression (Dehouche, 2021; Malik et al., 2023). It may also hinder self-editing, weaken critical thinking and creativity, and limit the development of higher-order writing skills (Iskender, 2023; Marzuki et al., 2023). Excessive dependence on AI may risk “cognitive decline,” with rapid solutions potentially harming critical thinking and problem-solving (Kasneciet al., 2023). Heavy reliance on AI-generated feedback may reduce learners’ original thinking and critical evaluation skills. LLMs may not capture the emotional and cultural nuances of language, potentially hindering students’ communication skills (Shidiq, 2023). While some students may overuse AI tools, others lack access due to limited technology or internet, raising concerns about fairness and equal learning opportunities (Marzuki et al., 2023). This digital divide raises questions about whether the potential benefits of AI-supported education can be equally accessible to all learners (Alzubi, 2024;Modhish& Al-Kadi, 2016). Another concern is that biased or incomplete information from generative AI tools can lead to linguistic injustice (Lucy & Bamman, 2021;Rawas,2024; Uzun, 2023). This risk stems from LLMs internalizing social biases, prejudices, and stereotypes in their training data, potentially leading to pedagogically problematic outcomes (Kasneciet al., 2023; Lund & Wang, 2023). These limitations suggest that AI integration into classrooms must be approached with caution.

The Rationale for Comparing ChatGPT-4, Gemini, and Copilot

Given AI-assisted writing’s potential and limitations, it is essential to examine how different generative AI tools function in education and how well they support learning. In response, this study compares three widely available tools: ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot. These three tools were specifically chosen for their widespread use, significant market presence, and distinct developmental philosophies, making them the most prominent and relevant platforms for a comparative study in today’s educational landscape. These tools have distinct development paths. ChatGPT, launched by OpenAI in 2022, quickly became a key player for its coherent, contextually appropriate responses and rapid evolution from GPT-3 to GPT-4 (Aydın & Karaarslan, 2022;Zaiarnaet al., 2024). In contrast, Microsoft Copilot, integrated into Microsoft’s productivity suite, is designed to streamline work processes, particularly in professional and academic writing (Microsoft, 2025). Google’s Gemini, a newer entrant to the AI space, is built to integrate with Google’s ecosystem and offers strong capabilities in document and content creation (Zaiarnaet al., 2024). While these tools share somefunctionalities, they differ in their design, development, and target use cases. These differences are not merely technical but also reflect distinct pedagogical potentials that can be linked to established theories. For instance, ChatGPT's conversational interface, with its dialogic-feedback model, can be seen as an extension of Vygotsky's ZPD theory, where the AI acts as a more capable peer. Gemini's multimodal capability and its integration within Google's ecosystem support a process-oriented writing approach (Flower & Hayes, 1981) by offering continuous support across different stages of writing. Similarly, Copilot's design, focused on efficiency and integration into Microsoft's productivity suite, aligns with pedagogical goals of reducing cognitive load and streamlining the writing workflow. Asadi et al. (2025) emphasize that more research is needed to explore how AI-driven feedback can be integrated with traditional methods to enhance writing instruction. Similarly, Carlson et al. (2023) encourage educators to explore how different tools can meet the specific needs of their learners. Including AI tools in the writing classroom shows great promise for addressing student difficulties and improving writing proficiency, especially when tools are selected based on their specific features and instructional contexts (Silva & Janes, 2020).

Rubric Design for Evaluating AI Writing Support

To evaluate how ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot supported students at different stages of the writing process, a 10-item rubric was developed by the researcher. The rubric includes criteria aligned with three key stages: brainstorming, outlining, and feedback. Brainstorming criteria such as argument diversity, relevance, and idea depth were informed by studies highlighting the cognitive and affective benefits of this prewriting strategy. Brainstorming has been shown to help students activate prior knowledge, generate creative ideas, and overcome common writing difficulties (Karim et al., 2016; T. H. Nguyen, 2020; Rao, 2007). It also supports student motivation by creating a low-pressure environment for idea exploration (T. H. Nguyen, 2020). More recently, AI tools like ChatGPT and Gemini have been recognized for their role in enhancing brainstorming by offering a broader range of perspectives and encouraging deeper engagement with the topic (Karanjakwut&Charunsri, 2025). These tools are increasingly viewed by both teachers and students as valuable supports for overcoming initial barriers and stimulating idea generation (Xu et al., 2024). In EFL contexts, AI-supported brainstorming can also ease anxiety and help organize thoughts before writing, thus improving overall expressive ability (Pratiwi &Julianti, 2022). Outlining criteria such as thesis strength, logical structure, and support development were informed by literature emphasizing the importance of organization and clarity in EFL writing (T. H. Nguyen, 2020;Wahyudin, 2018). The outlining stage serves as a bridge between idea generation and full-text drafting, and AI tools can facilitate this process by providing organizational templates or prompting students to visualize logical flow. Research suggests that outlining—whether AI-assisted or not—enhances coherence and planning, ultimately supporting writing quality (Pratiwi &Julianti, 2022; Xu et al., 2024). Feedback-related criteria, including specificity, actionability, and accuracy, were added to reflect the increasing use of automated writing evaluation (AWE) tools. While tools such as Grammarly can identify surface-level issues like grammar, vocabulary, and mechanics, they often fall short when addressing higher-order concerns such as content development, argument strength, or global organization. Students report appreciating the immediate feedback AI provides, especially in terms of revision accessibility and technical accuracy, but research shows the best outcomes occur when AI feedback is combined with teacher or peer guidance (Yuan, 2023). Grounded in existing literature and finalized through expert review, the rubric was designed for this study and has not been tested for generalizability across other contexts or learner populations. Its theoretical foundation and practical focus, however, suggest potential for adaptation and further development in future studies on generative AI in EFL writing instruction.

Methodology

Research Design

A mixed-methods design with a within-subjects 3×3 factorial framework evaluated three AI tools across three argumentative essay topics. Each participant experienced every Tool × Topic condition, allowing direct comparisons while controlling for individual differences.Randomization of topic order was initially considered; however, due to the voluntary and self-paced nature of participation outside of class hours, all topics were provided at the outset so students could manage their workload according to their own schedules. During data collection, several participants withdrew and were replaced by new volunteers. To ensure continuity and allow new participants to complete all tasks within the limited study period, the same full set of topics and materials was given to all, and topic order was not controlled.Tool interactions were logged for auditability. Data quality was maintained through routine screening for outliers and entry errors. Listwise handling was used for repeated-measures tests to preserve comparability, and no revisions were permitted after AI feedback to prevent contamination of subsequent measures.

The ten rubric criteria covered brainstorming (argument diversity, relevance, depth), outlining (thesis strength, logical structure, strength of supporting reasons, detail level), and feedback (feedback specificity, actionability, grammar and coherence). These were treated as continuous outcomes. Descriptive statistics were calculated, assumptions for repeated-measures models including normality and sphericity were tested, and Greenhouse–Geisser corrections applied as needed. Two-way repeated-measures ANOVAs tested main effects and the Tool × Topic interaction, with Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc comparisons. Effect sizes were reported as partial eta squared for omnibus tests and standardized mean differences for pairwise contrasts.

Open-ended responses were analyzed inductively so that emergent themes could contextualize quantitative patterns, and user experience shaped the perceived usefulness and relevance of AI-generated support.

Participants

The participants were 15 B+ level students at the preparatory school of a public university in Ankara,Turkiye, experiencing both their first year at the school and their first time writing full opinion essays in English. The language program follows a modular system, with the B+ level reflecting most CEFR Threshold features but functioning closer to upper-B1 in this institution. It marks the transition from paragraph writing to more complex academic genres, presenting challenges such as developing arguments and structuring ideas that may benefit from AI-assisted support.

Participation was voluntary, with no grades or performance-based evaluation. All participants signed consent forms, chose nicknames for anonymity, and worked independently outside class hours, representing different classrooms at the same level. Pre-survey results offered insights into their prior AI experience, writing challenges, and confidence in using AI for academic writing.

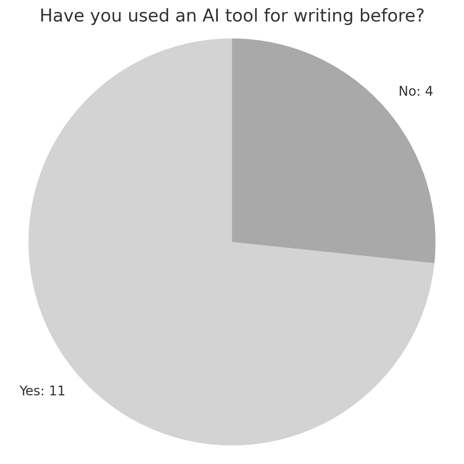

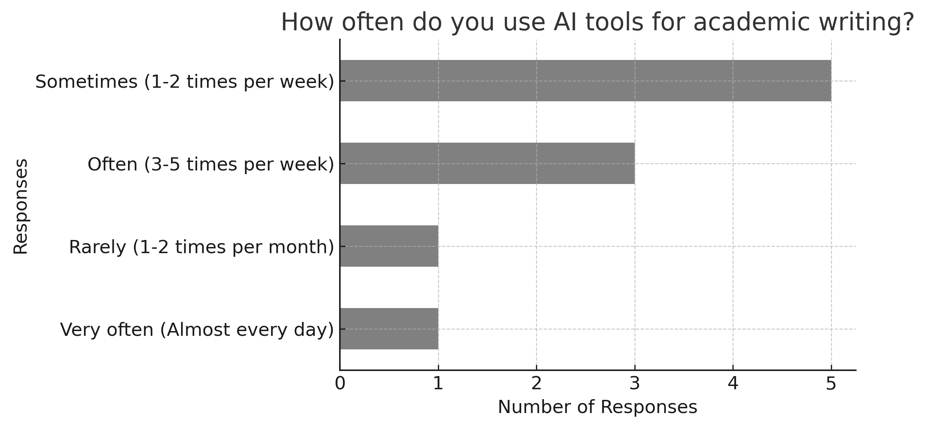

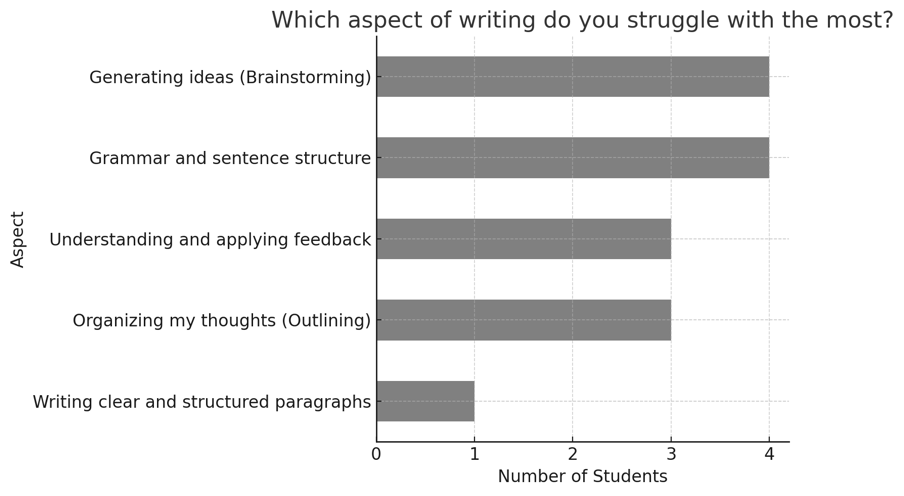

Pre-survey responses showed that 11 of the 15 students had previously used an AI writing tool, while 4 had not (Figure 1). Among those with prior use, ChatGPT-4 was the most frequently mentioned tool. Regarding usage frequency, 7 students reported using AI tools rarely (1–2 times per month), 4 students used them sometimes (1–2 times per week), 2 students used them often (3–5 times per week), and 2 students used them very often (almost every day) (Figure 2). When asked what they expected from an AI writing tool, the most commonly selected options were grammar correction, vocabulary support, and idea generation. Students rated their confidence in essay writing on a scale from 1 to 5, with most selecting scores between 2 and 4, indicating moderate confidence. A similar pattern emerged for comfort levels with AI in academic writing, indicating openness despite limited use. Finally, students most often identified organizing ideas, developing thesis statements, and maintaining coherence as their biggest writing challenges. (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Use of AI Tools Prior to the Study

Figure 2. Frequency of AI Tool Use for Academic Writing

Figure 3. Aspects of Writing Students Struggled with the Most

Data Collection

Data were collected using multiple tools: (a) a pre-survey and a post-survey administered via Google Forms; (b) three task-specific Google Forms (one for each essay topic); (c) an AI Writing Tool Evaluation Worksheet that guided students through prompt generation at each writing stage; and (d) screenshots of their interactions with the AI tools, which were submitted to a shared Google Drive folder. Students used ChatGPT-4, Gemini, and Copilot for brainstorming, outlining, and feedback in each task. Screenshots verified the completion of each stage and ensured the reliability and authenticity of the data.

The study focused on opinion essays, a genre defined by the program’s curriculum as a formal academic text presenting a reasoned argument for a specific point of view. Students were required to write an introduction with a clear thesis, body paragraphs with supporting details, and a concluding summary. Tasks were selected to align with the B+ curriculum objectivesand were based on opinion essay topics similar to those students typically complete in class:

Task 1: Traveling alone is better than traveling in a group.

Task 2: People who live in apartments shouldn't own pets.

Task 3: Some people believe that artificial intelligence will soon replace many jobs. Do you agree or disagree?

The worksheet guided students in crafting appropriate prompts for each AI tool at three key writing stages:

1.Brainstorming:Students asked each tool to list arguments for and against the topic.

2.Outlining:Students requested a structured outline including a thesis, three main ideas, and brief supporting details.

3.Feedback:Students submitted their essay to each tool and prompted them to give specific feedback on thesis strength, argument clarity, organization, grammar, coherence, and tone.

Students completed all tasks independently at their own pace. A Telegram group was used for communication, deadline reminders, support, and clarifying instructions. Some contacted the instructor by email, visited the office, or received one-on-one help, and a few without personal computers used the instructor’s computer. The initial face-to-face orientation was held on February 13, 2025, with a support session on February 27, 2025. All materials, including a presentation, instructional video, AI writing evaluation rubric, writing samples, and prompt sheets, were shared via Google Drive and in print.

The AI writing evaluation rubric was developed by the researcher with criteria for three stages: brainstorming, outlining, and feedback. Each criterion was based on principles from second language writing research and AI-integrated instruction. The rubric aimed to provide a standardized, objective evaluation of writing support, enhancing the reliability of data collection. To establish validity, the criteria were developed from the literature and then reviewed by one expert in English Language Teaching and one in Computer Education and Instructional Technology. Their feedback was incorporated to refine the criteria and ensure content validity and relevance to the academic context of B+ level students.

The prompt sheet was developed through extensive trial-and-error testing with ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot to determine concise, effective prompts for brainstorming, outlining, and feedback. Designed for clarity and pedagogical suitability for B+ level EFL learners, it was reviewed by a Computer Education and Instructional Technology faculty member.

Students evaluated the feedback from each AI tool but were not required to revise their essays based on it. Some requested and received additional teacher feedback for their own learning, but this was excluded from the formal analysis since the study focused on autonomous use of AI tools.

Analyzing of Data

Quantitative data from rubric-based evaluations were analyzed using descriptive statistics and two-way repeated-measures ANOVA to examine the main effects of AI tool and essay topic, and their interaction, on student ratings across ten writing criteria for brainstorming, outlining, and feedback. Data were screened for outliers and entry errors, and assumptions of normality and sphericity were checked; Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied when necessary. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons used Bonferroni adjustments. Effect sizes were reported as partial eta squared for omnibus tests and standardized mean differences for pairwise contrasts. All analyses were conducted in JASP. No revisions were allowed after AI feedback to avoid contamination of subsequent measures, and listwise handling was applied for repeated-measures tests to maintain comparability.

Qualitative data from open-ended responses were analyzed inductively using thematic analysis. Coding and thematization were conducted systematically by the researcher, with an audit trail maintained to document coding decisions and theme development. Codes and themes were iteratively reviewed and refined to enhance consistency and minimize bias. Microsoft Excel was used to organize responses, identify recurring keywords, and group comments thematically across different writing stages and evaluation questions.

To strengthen validity, this study used methodological triangulation by combining quantitative rubric scores with qualitative open-ended responses. Quantitative data were analyzed first to identify patterns and significant effects, followed by qualitative analysis to provide context and contrast. Integrating both data types enabled cross-validation and a fuller understanding of participants’ experiences with the AI tools.

Findings

This section reports the findings from the evaluation of three generative AI tools: ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot. Table 1 summarizes the mean scores and two-way repeated measures ANOVA results for each rubric criterion, indicating differences related to both the AI tool and the essay topic. The findings are presented under three categories: brainstorming, outlining, and feedback. Each section integrates quantitative results with qualitative student feedback to provide a comprehensive analysis of tool effectiveness.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for AI Tool Performance by Rubric Criterion and Essay Topic

| Rubric Criterion | AI Tool | Topic 1 (M, SD) | Topic 2 (M, SD) | Topic 3 (M, SD) |

| Argument Diversity | ChatGPT | 3.867 (0.915) | 3.667 (1.291) | 4.000 (0.926) |

| Gemini | 3.800 (0.941) | 3.867 (0.834) | 4.200 (0.862) | |

| Copilot | 3.933 (0.704) | 3.933 (0.704) | 4.000 (1.000) | |

| Relevance | ChatGPT | 4.667 (0.488) | 4.333 (0.816) | 4.200 (1.146) |

| Gemini | 4.533 (0.915) | 3.867 (0.743) | 4.133 (1.125) | |

| Copilot | 4.600 (0.632) | 4.067 (0.799) | 4.400 (1.056) | |

| Depth of Arguments | ChatGPT | 3.600 (1.121) | 4.333 (0.816) | 3.933 (1.100) |

| Gemini | 3.933 (0.884) | 4.133 (0.743) | 4.000 (1.069) | |

| Copilot | 4.067 (0.799) | 3.733 (0.799) | 4.067 (1.033) | |

| Thesis Strength | ChatGPT | 3.933 (1.033) | 4.000 (1.000) | 4.200 (1.014) |

| Gemini | 3.733 (0.799) | 3.933 (0.961) | 4.000 (1.069) | |

| Copilot | 3.733 (0.704) | 4.067 (0.961) | 3.933 (0.961) | |

| Logical Structure | ChatGPT | 4.067 (0.884) | 4.067 (0.704) | 4.133 (0.834) |

| Gemini | 4.067 (0.884) | 3.867 (0.640) | 3.733 (0.884) | |

| Copilot | 4.067 (0.799) | 3.867 (0.640) | 4.067 (0.884) | |

| Strength of Supporting Reasons | ChatGPT | 4.000 (1.000) | 4.000 (0.756) | 4.000 (1.134) |

| Gemini | 3.867 (0.743) | 4.467 (0.743) | 4.067 (1.163) | |

| Copilot | 3.867 (0.915) | 4.267 (0.884) | 3.867 (1.060) | |

| Detail Level | ChatGPT | 3.400 (1.121) | 4.000 (1.069) | 4.000 (1.000) |

| Gemini | 3.867 (1.060) | 3.800 (1.082) | 3.867 (1.187) | |

| Copilot | 3.600 (0.632) | 3.733 (1.223) | 3.800 (0.941) | |

| Feedback Specificity | ChatGPT | 4.133 (0.990) | 4.333 (0.900) | 4.067 (0.961) |

| Gemini | 3.733 (1.100) | 4.133 (0.834) | 4.267 (0.799) | |

| Copilot | 3.733 (0.704) | 4.067 (0.884) | 4.067 (0.884) | |

| Actionability | ChatGPT | 4.267 (0.594) | 4.267 (0.704) | 4.467 (0.743) |

| Gemini | 3.667 (1.234) | 4.067 (0.704) | 4.200 (0.676) | |

| Copilot | 4.000 (0.655) | 4.067 (0.704) | 3.667 (0.976) | |

| Grammar & Coherence Feedback | ChatGPT | 4.267 (0.594) | 4.333 (0.900) | 4.467 (0.743) |

| Gemini | 3.800 (1.320) | 3.867 (0.743) | 4.267 (0.961) | |

| Copilot | 4.000 (0.655) | 4.067 (0.884) | 4.200 (0.775) |

Note.M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Table 2. Mean Scores and Repeated Measures ANOVA Results for AI Tool and Essay Topic

| Rubric Criterion | Factor | df | F | p | η² | Significant Difference (p < .05) |

| Argument Diversity | Topic | 2,28 | 0.640 | .535 | 0.044 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 0.414 | .665 | 0.029 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.314 | .868 | 0.022 | NO | |

| Relevance of Arguments | Topic | 2,28 | 3.109 | .060 | 0.182 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 3.664 | .039 | 0.207 | YES (p < .05) | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.769 | .550 | 0.052 | NO | |

| Depth of Arguments | Topic | 2,28 | 0.398 | .676 | 0.028 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 0.098 | .907 | 0.007 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 1.812 | .139 | 0.115 | NO | |

| Thesis Strength | Topic | 2,28 | 0.653 | .528 | 0.045 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 0.455 | .639 | 0.032 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.178 | .949 | 0.013 | NO | |

| Logical Structure | Topic | 2,28 | 0.287 | .753 | 0.020 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 0.966 | .393 | 0.065 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.500 | .736 | 0.035 | NO | |

| Strength of Supporting Reasons | Topic | 2,28 | 0.972 | .391 | 0.065 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 0.375 | .691 | 0.026 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.801 | .530 | 0.054 | NO | |

| Detail Level | Topic | 2,28 | 0.853 | .437 | 0.057 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 0.216 | .807 | 0.015 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.619 | .651 | 0.042 | NO | |

| Feedback Specificity | Topic | 2,28 | 1.754 | .192 | 0.111 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 0.645 | .532 | 0.044 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.473 | .755 | 0.033 | NO | |

| Actionability | Topic | 2,28 | 0.507 | .608 | 0.035 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 5.025 | .014 | 0.264 | YES (p < .05) | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 1.526 | .207 | 0.098 | NO | |

| Grammar & Coherence Feedback | Topic | 2,28 | 1.057 | .361 | 0.070 | NO |

| Tool | 2,28 | 2.860 | .074 | 0.170 | NO | |

| Topic×Tool | 4,56 | 0.198 | .938 | 0.014 | NO |

Table 3. Post-hoc Pairwise Comparisons for Relevance of Arguments by Tool

| Mean difference | Standard error | df | t | pbonf | ||

| ChatGPT | Gemini | 0.222 | 0.090 | 14 | 2.467 | .081 |

| Copilot | 0.044 | 0.079 | 14 | 0.564 | 1.00 | |

| Gemini | Copilot | -0.178 | 0.091 | 14 | -1.948 | .215 |

Note. P-value adjusted for comparing a family of 3 estimates.

Note. Results are averaged over the levels of: Topic

Table 4. Post-hoc Pairwise Comparisons for Actionability by Tool

| Standard error | df | t | pbonf | ||

| ChatGPT | Gemini | 0.124 | 14 | 2.874 | .037 |

| Copilot | 0.136 | 14 | 3.106 | .023 | |

| Gemini | Copilot | 0.167 | 14 | 0.400 | 1.00 |

Note.P-value adjusted for comparing a family of 3 estimates.

Note.Results are averaged over the levels of: Topic

Table 5. Thematic Analysis of Student Reasoning Patterns

| Brainstorming | Outlining | Feedback | Future Use | TOTAL | |

| Clarity/Understandability | 4 | 19 | 11 | 6 | 40 |

| Detail/Comprehensiveness | 7 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 36 |

| Effectiveness/Efficiency | 6 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 22 |

| Examples/Variety | 5 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 20 |

| Structure/Organization | 0 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 9 |

| Grammar/Language | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Interface/Presentation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 |

| Specificity/Precision | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

Brainstorming

The brainstorming phase encompasses the initial generation and development of opinion essay content, specifically evaluating the diversity, relevance, and depth of arguments produced by the AI tools.

Analysis of argument diversityrevealed no statistically significant differences among the three AI tools, with mean scores remaining consistent across thetools (Table 1). There were also no significant effects of topic or tool-topic interaction (Table 2), indicating that all tools are equally capable of generating diverse content for opinion essays, regardless of topic.

For argument relevance,a significant main effect of Tool,F(2, 28) = 3.66,p= .039, η² = .21, indicating that the type of AI tool used influenced the relevance of arguments (Table 2). However, post hoc pairwise comparisons using Bonferroni adjustment (Table 3) did not reveal any significant differences between tools: ChatGPT vs. Gemini (Mean Difference = 0.22,p= .081), ChatGPT vs. Copilot (Mean Difference = 0.04,p= 1.00), and Gemini vs. Copilot (Mean Difference = -0.18,p= .215). There were no significant main effects of Topic or Topic × Tool interaction. Thus, while the overall effect of Tool was statistically significant, no specific tool outperformed the others in producing more relevant arguments.

Argument depth showed no significant differences between the AI tools or topics,and no interaction effects wereobserved (Tables 1 and 2). These results indicate that all three AI tools offer comparable depth in opinion content generation across topics.

Qualitative responses on brainstorming preferences showed more variation than for other tasks. Among the 15 students, 5 preferred ChatGPT-4, 4 chose Gemini, 1 favored Copilot, 4 rated all tools similarly, and 1 found none helpful. Comprehensiveness (7 mentions) and effectiveness (6 mentions) were the most cited reasons (Table 5). While quantitative results indicated a difference in the relevance of arguments across tools, post-hoc comparisons showed that this difference was not statistically significant. Students nevertheless expressed clear perceptions of what made certain tools more helpful. For example, Pancake found Gemini “the most helpful” for brainstorming because it gave “lots of item[s]” and offered a wider variety of ideas. Belma preferred ChatGPT-4, noting it “helped me narrow down relevant points.” Perceptions of diversity and depth were broadly similar across tools. Gemini was frequently linked to detail and insight, Copilot to clarity and uniqueness, and ChatGPT-4 to strong or creative content. Still, many students found the tools toproducecomparable brainstorming support overall.

The outlining phase evaluates the structural organization of opinion essays, including thesis development, logical structure, strength of supporting reasons, and level of detail.

The thesisstrength did not differ significantly across AI tools, with no significant main effect of topic or interaction effects observed (Table 2). As indicated in Table 1, mean scores were comparable across all three tools. This shows that all three tools are equally capable of producing strong thesis statements.

The logical structure was consistent across all AI tools, with no significant differences between tools, topics, or interaction effects observed (Tables 1 and 2). This suggests all three AI tools are equally capable of organizing opinion content coherently.

No significant differences were found inthe strength of supporting reasonsbetween AI tools, topics, or their interaction (Tables 1 and 2). Findings show all three tools performed similarly in generating strong supporting reasons.

A detailed analysis revealedno significant differences between AI tools, topics, or their interaction (Tables 1 and 2). Although Gemini scored slightly higher on detail, Table 1 shows these differences were not significant, indicating comparable performance across tools in providing detailed opinion content.

Qualitative responses on outlining preferences showed clearer distinctions between tools. Of the 15 students, 7 preferred Gemini, 5 Copilot, and 3 ChatGPT-4. Clarity (19 mentions) and variety of examples (9 mentions) were the most cited reasons (Table 5), with many describing a “clear and organized structure” and a “wide range of examples for main points.” Unlike brainstorming, no students rated all tools similarly, suggesting greater perceived differences in this phase. Copilot was often praised for clarity and structure, as Ares noted it provided a “strong and clear thesis” and was “logically structured.” Gemini was frequently associated with depth and detail, with Serendipity commenting it “gave the mostdetails,” whilednz_ preferred ChatGPT-4 for offering “more options.” These patterns reflect the stronger individual preferences students formed during outlining.

The feedback phase assesses the AI tools' capacity to provide specific, actionable, and grammatically coherent feedback on opinion essays.

Feedback specificity showed no significant differences between tools, topics, or their interaction (Tables 1 and 2). Despite the numerical differences evident in Table 1, all three tools demonstrate statistically equivalent capacity for providing specific feedback on opinion essays.

For the Actionability criterion, the main effect oftheAI tool was statistically significant (Table 2). Post-hoc pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni correction indicated that ChatGPT-4 received significantly higher scores than both Google Gemini (p= .037) and Microsoft Copilot (p= .023) (Table 4). No significant difference was found between Gemini and Copilot (p= 1.000). Mean scores across topics were highest for ChatGPT-4 (M≈ 4.33), followed by Gemini (M≈ 3.98) and Copilot (M≈ 3.91), indicating that students perceived ChatGPT-4’s feedback as more actionable than that of the other two tools.

Grammar and coherence feedback did not differ significantly between tools, topics, or their interaction (Tables 1 and 2). Results showthat all three tools performed equally in providing feedback on grammar and coherence.

Qualitative responses to feedback preferences showed the greatest differentiation among tasks. Of the 15 students, 8 preferred ChatGPT-4, 5 Gemini, and 2 Copilot. Detail (16 mentions) and clarity (11 mentions) were the most cited reasons, with many highlighting “longer and more detailed” or “clear and understandable” feedback. ChatGPT-4 emerged as the clear favorite, often described as providing not only specific but also actionable suggestions.Şampiyonpatinoted it “explained all my mistakes in detail,” while Ares praised its “clear revision steps and precise corrections.” Gemini also received comments on step-by-step support, such as Pancake’s mention of guidance for correcting mistakes. Copilot was valued by a few,such as Harmony, for being conciseand direct, but was less frequently described as revision-oriented. These reflections align with the quantitative finding that ChatGPT-4 scored significantly higher than both Gemini and Copilot for actionability, while no significant difference was found between Gemini and Copilot. This alignment between statistical results and student perceptions reinforces the view that ChatGPT-4’s feedback was not only more comprehensive but also more readily applicable in the revision process.

Student Reflections After the Study

After completing all three writing tasks and engaging with ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot, students were asked to reflect on their overall experiences. The post-study survey included four open-ended questions: (1) How did the AI tools help you improve your writing? (2) What difficulties did you encounter while using the AI tools? (3) Which tool did you find the most helpful, and why? (4) Would you recommend using AI tools for future writing tasks? Why or why not?The responses provided valuable insights into students’ evolving attitudes toward AI-assisted writing, highlighting both benefits and challenges.

Post-study reflections from 15 students revealed that AI tools were perceived as most beneficial for grammar and language correction (7 mentions) and providing feedback for learning (7 mentions), followed by idea generation and brainstorming support (5 mentions). Students valued the immediate feedback and error identification capabilities of the tools.

Technical issues like internet connectivity and upload problems were the most common challenges (5 mentions), while 4 students reported no difficulties. Device limitations, especially using mobile phones instead of computers, also posed challenges for some.

When asked to identify the most helpful tool overall, 5 students preferred ChatGPT-4, 4 Gemini, and 1 Copilot, while 5 expressed mixed or equal preferences. Although task-specific preferences were clear, overall preferences varied more among individuals.

Ten ofthe fifteen students recommended using future AI tools, highlighting faster feedback, independent learning, and easy access to help. Three gave conditional recommendations, expressing concerns that over-reliance might hinder independent thinking.

Discussion

This study compared ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot in supporting B+ level EFL students during brainstorming, outlining, and feedback in opinion essay writing. Drawing on quantitative rubric scores and qualitative reflections, it explored whether any tool outperformed the others and how students experienced each stage. The discussion interprets these findings in relation to existing literature and student perceptions.

Brainstorming

Quantitative results for brainstorming showed no statistically significant differencesamong ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot in terms ofargument diversity or depth, indicating comparable idea quality. Students’ perceptions supported this finding, with several describing the tools as producing similarly comprehensive and useful ideas. For instance,Canshcharacterized Gemini’s ideas as “detailed, well-developed, and insightful,” while Cloud felt that “they were all the same, they said the same things.” For argument relevance, a difference was observed across tools; however, post-hoc analysis showed that this difference was not statistically significant. Up-to-date comparative AI technology reviews frequently evaluate the strengths of popular generative AI tools. Inrecent comparisons, ChatGPT is consistently highlighted for its creative writing and brainstorming capabilities, while Gemini is noted for its multimodal reasoning within the Google ecosystem, and Copilot is recognizedfor its productivity-oriented integration with the Microsoft environment (DataStudios, 2025;UpforceTech, 2025). This consistent emphasis on ChatGPT’s brainstorming strengths may help explain why, despite the absence of statistical significance, it achieved the highest average scores for argument relevance in the brainstorming stage.

Some participants preferred ChatGPT-4 for its user-friendliness and speed, echoingAlmumenandJouhar’s(2025) finding that it can enhance argument quality and supporting evidence through a rich brainstorming process.Belma described it as “easy and fast,” whileSteelShadowemphasized that “it gave details so much” and was “more comfortable.” Copilot received fewer mentions, butŞampiyonpatiappreciated its “broad brainstorming session” and ability to anticipate “potential issues.”

Overall, these perceptions confirm that while quantitative data showed parity in performance, subjective experiences varied. Students’ comments indicate that preferences were shaped bythe quality of ideasas well as clarity, speed, and perceived creativity, with Gemini noted for offering varied perspectives (Karanjakwut&Charunsri, 2025).

Outlining results showed no significant differences between the three tools across thesis strength, logical structure, supporting reasons, and detail level, suggesting all can help students structure essays effectively. However, qualitative data revealed clearer task-specific preferences: Gemini was chosen by 7 students, Copilot by 5, and ChatGPT-4 by 3, with clarity and variety of examples most often cited. These findings align with Azmi andFithriani(2025), who reported that Gemini improved organization and coherence by supporting clearer paragraph transitions and logical sequencing.In our study, Cloud appreciated Gemini’s clarity in outlining, andCanshnoted its “wide range of examples.” Similarly,Zainurrahman(2024) observed that Copilot can generate clear, logically divided outlines, which some of our participants found useful. ECRN, for example, chose Copilot for brainstorming but preferred ChatGPT-4 for feedback, noting that both were “detailed.”

ChatGPT-4’s outlining strengths, described byAlmumenandJouhar(2025) as producing coherent structures and exposing students to sophisticated text patterns, were echoed by Ares, who found its outlines “accurate and clear.” However, the lack of significant differencessuggests that these strengths were not unique to anyone tool. Student comments suggest that outlining preferences were driven more by clarity, structure, and breadth of examples than by measurable differences.

In the feedback phase, no significant differences were found between tools in specificity, grammar,and coherence. However, actionability showed a statistically significant difference, with ChatGPT-4 scoring higher than both Google Gemini and Microsoft Copilot, while no significant difference was found between Gemini and Copilot. ChatGPT-4 was most preferred, chosen by 8 students, followed by Gemini (5) and Copilot (2).

Students valued ChatGPT-4’s detailed, clear, and actionable feedback, consistent with Bruhn and Marquart (2025), who found it useful for early drafting and language feedback.Dnz_ highlighted its “more detailed and explanatory grammar feedback,” and Asiye described its feedback as “better and more detailed.” These perceptions align with Escalante et al. (2023), who describe ChatGPT as an intelligent tutor providing personalized, targeted guidance. Students also appreciated the non-judgmental nature of AI feedback, which Bruhn and Marquart (2025) linked to reduced anxiety in revision. ECRN admitted they sometimes avoided asking teachers or peers questions,but felt comfortable consulting AI. Similarly, Cloud valued the independence it provided, saying, “You can study on your own, you do not need anyone else.” Lu et al. (2024) noted that immediate feedback can enhance metacognitive reflection, a benefit echoed by Zeyzey, who “learned a lot from the instant feedback.”

Gemini’s feedback performance was competitive, especially in coherence and cohesion, as D. L. Nguyen et al. (2025) found. Hera described its feedback as “very detailed and clear.” However, limitations in spelling and word formation feedback noted by D. L. Nguyen et al. (2025) may help explain why it scored lower than ChatGPT-4 in grammar-related criteria.

Copilot’s straightforward and easy-to-understand feedback, as described byZainurrahman(2024), was appreciated byŞampiyonpatifor its breadth, though fewer students preferred it overall.

The statistical advantage of ChatGPT-4 in actionability was reinforced by qualitative comments describing its feedback as offering clear next steps and essay-specific suggestions, aligning with Woo et al. (2023), who suggest diverse information can foster creative thinking. Overall, although ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot performed similarly across most feedback criteria, ChatGPT-4 stood out for theactionable guidance it provided.

Conclusion

This study examined the effectiveness of ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot in supporting B+ level EFL students through brainstorming, outlining, and feedback stages of opinion essay writing. Quantitative analysis revealed no statistically significant differences between the tools for most rubric criteria, with the only significant effect being in the feedback stage, where ChatGPT-4 scored higher than both Gemini and Copilot for actionability.During the brainstorming stage, a difference in argument relevance was observed across tools; however, this differencewas not statistically significant after post-hoc analysis. Qualitative findings highlighted clear task-specific preferences: Gemini was often valued for clarity and variety in brainstorming and outlining, ChatGPT-4 was favored for detailed, clear, and actionable feedback, and Copilot, while less frequently selected, was appreciated for certain organizational and brainstorming strengths. These results suggest that while all three AI tools are objectively comparable in many aspects of performance, individual learner experiences and perceptions can vary substantially depending on both the task and the tool’s characteristics.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Educational Practice

The findings suggest AI integration in writing instruction is most effective when students can choose the tool that suits each stage of the process. Rather than prescribinga single platform, educators can offer multiple AI tools and encourage theirstrategic use for brainstorming, outlining, and feedback. Careful topic selection is essential, as familiarity and interestsignificantly influence the relevance of the arguments generated. Training in effective prompt design can help students obtain clearer, targeted outputs, and AI feedback should complement rather than replace teacher input. To promote equity, institutions should address technical barriers such as device and connectivity issues and provide adequate resources. Finally, classroom discussions on AI’s benefits and limitations can encourage students toutilize these tools to enhance, rather thanreplace, their own critical thinking and creativity.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future research could develop and validate a reliable, widely applicable rubric for evaluating AI tools across educational purposes. While the rubric in this study was tailored for a small group and based on literature and expert review, a more robust, widely tested instrument would improve comparability across contexts. Including larger, more diverse student populations could enable richer analysis, such as comparisons by proficiency level, preparatory school setting, and cross-country context. Such studies could clarify how contextual and demographic factors influencethe performance of AI tools and learner perceptions, offering a more comprehensiveunderstanding of their role in language learning.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. The sampleconsisted of 15 B+ level students from a single preparatory program in Turkey; therefore,the results may not be generalizable to other proficiency levels, educational settings, or institutions.

While the quantitative phase involved a small sample (N = 15), the data collection was intensive and comprehensive. Each participant completed three essay tasks on different topics, using all three AI tools for brainstorming, outlining, and feedback, and provided detailed ratings and reflections for each condition. This repeated-measures design generated multiple observations per participant, enhancing reliability and statistical power despite the modest sample size. The demanding protocol limited the number of participants but enabled in-depth, controlled analysis of tool and topic effects. Findings should be viewed as exploratory and context-specific, with future research encouraged to use larger, more diverse samples.The topic order was not randomized, as all topics were provided at the outset to accommodate the self-paced format and thereplacement of withdrawn participants; thus, potential sequencing effects cannot be ruled out.The study spanned only three weeks and three opinion essay tasks, which did not allow for long-term tracking of students’ writing development or analysis of how tool use might influence writing habits over time. Another limitation is the use of free versions of ChatGPT-4, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot, which may offer reduced functionality compared to paid or updated versions. Since access to GPT-4 ended during the finalization of this article, future replications may involve newer versions,which could affectcomparability. The study was also a preliminary investigation aimed at identifying the most suitable AI tool for this learner group. Broader areas such as teacher feedback comparison, detailed analysis of student–AI interactions, and long-term writing improvement were outside the current scope but could be explored in future research. The evaluation rubric, although informed by literature and reviewed by experts, was designed for this small cohort and not tested for broader validity or reliability, which limits its applicability beyond thisstudy. Reliance on student self-reports for much of the qualitative data may have introduced bias, as reflections could have been shaped by prior experiences or immediate impressions rather than sustained evaluation. Technical and environmental factors such as device type, internet stability, and prior familiarity with AI tools may also have influenced interactions with each platform. These constraints, together with the focus on a single proficiency level in one institution, mean that caution is needed when applying these findings to other learner groups or contexts.

Ethics Statements

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Ankara University. All participants were informed about the study and its procedures, and they provided written informed consent to participate voluntarily. The study complied with ethical standards for research involving human subjects.

The author would like to thank the students who voluntarily participated in the study and the instructors who provided valuable feedback during the development of the data collection tools.

Generative AI Statement

As the author of this work, I used the AI toolChatGPT-4o (OpenAI, paid version)for the purpose oflanguage polishing, sentence rephrasing, and improving clarity.After using this AI tool, I reviewed and verified the final version of the manuscript. I take full responsibility for the content of the published work.