Introduction

In non-industrial societies, children, especially girls, start engaging in considerable household labor from a young age, with some groups reporting daily workloads exceeding five hours by early adolescence (Larson & Verma, 1999). In contrast, children in post-industrial societies typically spend less than one hour per day on household tasks (Larson & Verma, 1999). This shift is attributed to structural transformations such as industrialization, the expansion of formal schooling, and rising family incomes, collectively contributing to a global decline in children’s time spent on domestic labor, especially in more developed regions (Larson & Verma, 1999; Soares et al., 2012). These changes have opened up time for developmentally enriching activities, such as learning, play, and leisure. However, the redistribution of domestic responsibilities has remained gendered: across nearly all societies, girls continue to spend more time on housework than boys (see Ahn & Yoo, 2022; Busetta et al., 2019; Gibby,2021; Gracia et al.,2021; Grasmeijer et al., 2024; Hu & Mu, 2020; Jago et al., 2005; Keane et al., 2022; Larson & Verma, 1999).

While extensive research has linked heavy housework burdens to a variety of negative consequences in adulthood (see e.g., Bryan & Sevilla-Sanz, 2011; Carmichael et al., 2022; Hersch & Stratton, 1997), the literature on adolescents is limited and predominantly descriptive, focusing on the amount and frequency of domestic labor rather than its impact on educational attainment and broader life outcomes. Recently, a handful of articles (Keane et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Zhang & Ye, 2024) steered the conversation on the effects of housework into the area of causal analysis, estimating a significant but moderate positive effect of housework on academic achievement. Building on this emerging literature, the present study aims to explore the association between the frequency of adolescent participation in household chores and their academic and physical skills in a European context, using a fixed-effects framework. While this approach does not establish causal effects, it goes a step beyond most earlier studies by focusing on how fluctuations in an individual student's housework frequency relate to changes in their own academic and fitness skills over time. This helps reduce the influence of stable, unobserved differences between individuals, such as personality or upbringing, that might otherwise distort the results.

Literature Review

Historical and Theoretical Framework

Within educational science, the theory of embodied cognition posits that cognitive processes are inherently interconnected with bodily movements and sensory experiences, rather than being confined to brain function alone (see, e.g., Farina, 2020; Shapiro & Stolz, 2019). Because all information is perceived, processed, and interpreted through the body’s actions and sensory inputs, the motor and sensory systems are not merely supportive, but constitutive of conceptual understanding. This framework has been predominantly applied to younger children and motor-skill learning contexts, documenting benefits for early learners’ executive function and academic outcomes; however, applications with adolescents have been relatively limited until recently (Everaert et al., 2023). A pilot study by Everaert et al. found that secondary students who practiced embodied cognitive learning showed moderate improvements in working memory, classroom well-being, and performance in subjects like language and geography.

Building on this perspective, emerging research on housework and skill development explores whether such housework-related (embodied) routines show associations with adolescents’ cognitive and academic development. Many common housework tasks can be understood as natural examples of embodied cognition (Zhang & Ye, 2024): they are perceptual-motor or cognitive tasks (Godwins, 2022) requiring the coordination of physical actions and mental processes, such as planning, sequencing, applying literacy (e.g., reading instructions) or numeracy (e.g., measuring ingredients), communicating with others, and making real-time decisions—skills that may develop through everyday embodied practice.

Housework and Cognitive Skills

As Zhang and Ye (2024, p. 2) observe, “the academic community has not yet developed a great deal of research experience around the relationship between housework and the development of academic performance.” Indeed, empirical studies on this topic remain rare and yield mixed, inconclusive findings. This section enumerates the methods and findings of this literature on a country-by-country basis.

In the United States, we identified two studies on the role of housework in skill development. First, Telzer and Fuligni(2009) studied longitudinal daily diary data collected from 563 high school students of Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds from three public high schools in Los Angeles. They looked at days (occasions) and total time spent on family assistance (chores and sibling care) and compared them to achievement (GPA scores) via hierarchical linear models, using data from 9th to 12th grade. While time had no effect, the number of days had a significant association with GPA for adolescents from a Mexican or Chinese heritage, compared to those from a European background. This association was upheld even after controlling for generational status, socioeconomic background, and family composition. Gender-based heterogeneity was not detectable in their estimates. Their statistical method, a random-intercept, random-coefficient model with clustered standard errors, is conceptually similar to the random effects model applied in our analysis. Second, Wolf et al. (2015) analyzed a cross-sectional sample of 504 low-income, English-speaking African American and Latino adolescents who studied in New York in 2010. They applied cluster analysis to survey-collected time-use patterns and examined the academic outcomes (GPA, standardized tests) for each cluster. Their results indicated lower performance for those with a high focus on maintenance-related daily activities, such as housework, compared to children with an academic focus or a social focus.

In Australia, Tepper et al. (2022) investigated the relationship between executive functions (working memory, inhibitory control) and engagement in routine domestic tasks (conceptualized as chores related to self-care or family-care) on a cross-sectional sample of 207 Australian children (ages 5 to 13). They applied simple linear regression, controlling for demographics, to find a moderate but significantly positive association between involvement in domestic tasks and executive functions. They observed no significant gender-based heterogeneity.

In India, Sharma and Shah (2025) examined adolescents (ages 12-23) from rural Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, using data from the UDAYA survey (Population Council, 2017). They operationalize housework as self-reported unpaid domestic work hours on the day preceding the survey. Outcomes measured include dropout rates, absenteeism, and literacy/numeracy skills. They applied logistic regression and found a strong negative relationship: higher chore hours are significantly associated with increased dropout, absenteeism,lower literacy, and—to an even higher extent—arithmetic proficiency, particularly among girls. The study underscores this gendered heterogeneity and contextualizes findings within prevalent gender norms, economic necessity, and norms surrounding adolescent labor.

On a longitudinal sample of ~5,000 8- to 18-year-olds from four low- to middle-income countries—Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam—Keane et al. (2022) estimated that household chores undermine cognitive growth only when they replace schooling or study time; when chores substitute merely for leisure, the evidence of any cognitive harm is minimal. This effect is ubiquitous across all ages of children, and consistent across model specifications: value-added, fixed effects, and two-stage least squares estimators yielded compatible estimates.

A cross-sectional study of 1,535 children in Zambia (Tan et al., 2023) looked at the association between complex chores (such as preparing meals or looking after children) and mathematics skills. Their analysis reveals a crossover pattern: household chores enhance foundational numeracy for children who do not attend school regularly, yet once classroom attendance exceeds a threshold, those same chores sharply depress academic performance. This attendance-contingent effect is especially pronounced among girls and only mildly evident among boys.

Finally, recent studies in China have yielded mixed findings on the association between adolescents’ time spent on housework and academic results. However, studies employing more robust methods have found positive effects. Hu and Mu (2020) analyzed a nationally representative sample of 19,487 middle school students (mean age 13.7) from the 2013/14 sweep of the China Education Panel Study using multilevel models. They found a significant association between weekly time usage and cognitive development (measured via standardized tests of linguistic, graphical, and mathematical reasoning). By contrast, Wang et al. (2022) report positive academic impacts of housework in he 5th and 9th grades. Using data from the 2020 Monitoring of Students’ Academic Quality in Basic Education in Jiangsu Province (~103,000 5th-graders and ~101,000 9th-graders), they measured housework participation with a dummy variable (regular vs infrequent), recoded from an original 4-point scale. Employing OLS regressions with Coarsened Exact Matching to address selection bias, Wang et al. find that frequent housework is associated with higher standardized test scores, albeit the effect is small for 9th graders (.02 SD). To draw an even sharper contrast, Zhang and Ye (2024) used propensity score matching to analyze the same dataset as Hu and Mu (2020) but found positive effects (.21 SD) of housework on standardized academic performance (measured via mean standardized test scores in mathematics, Chinese, and English). They combined ordinary linear and quantile regression with propensity score matching, and argued that their varied set of background variables (see Table A1) captures the exogeneity in housework participation and bypasses the conditional independence assumption.

To summarize, the research results indicate mainly positive effects in China and Australia, and negative effects in India,as well as in urban areas of the United States among minority populations and among school-attending children in Zambia. Evidence of null effects is reported by a study looking at four countries: Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam. At first glance, findings suggest that cultural background influences the relationship between housework frequency and educational outcomes. Importantly, however, these results are not directly comparable as the listed papers apply a variety of methods, ranging from statistical tests (Wolf et al., 2015) to longitudinal models (Keane et al., 2022; Telzer & Fuligni, 2009), and some studies even apply propensity score matching to reduce sample-selection bias (Wang et al., 2022; Zhang & Ye, 2024). Comparison of results is further limited by the applied measures. For instance, while Telzerand Fuligni (2009) argue for the use of daily housework frequency measures, such as the one employed in the current paper, others, including Keane et al. (2022), utilize time-use data to account for precise time allocation patterns. Attributing cross-national differences to cultural context is therefore unwarranted; methodological heterogeneity across studies could explain much of the differences, underscoring the need for harmonized analytical approaches before conclusions can be drawn.

Housework and Fitness

There is limited evidence on the relationship between fitness and the frequency of housework during adolescence. To our knowledge, there are only two relevant studies, both by Tanucan et al. (2022, 2024). In their first paper (Tanucan et al., 2022), the researchers provided experimental evidence from the Philippines that housework-based exercise (overseen by fitness professionals) can have effects similar to conventional exercise. Arm flexibility and arm and core muscle strength of children improved similarly in both housework-based and traditional exercise. Girls’ cardiovascular endurance and leg flexibility also improved to the same extent, but boys in the housework-based exercise group lagged behind boys doing traditional exercise in these metrics. The sole domain in which conventional exercise proved to be generally more effective than housework-based exercise is the lowering of BMI. The second analysis (Tanucan et al., 2024) focused on obese 18-to 19-year-olds, examining the effects of a structured housework-based exercise program on fitness indicators. Similar to their earlier study, the researchers found that housework-based exercise led to significant improvements in muscular strength, endurance, and flexibility, with gains comparable to those observed in conventional exercise programs. Both male and female participants demonstrated enhanced push-up performance and plank duration, indicating improvements in upper body and core strength. This study also gave nuance to the findings of their 2022 study, as this intervention led to a substantial reduction in BMI for male participants, suggesting that housework-based exercise can effectively lower body weight, at least in certain populations. Female participants experienced greater improvements in cardiovascular endurance and flexibility. Overall, their research suggests that integrating housework into adolescents’ fitness routines can serve as a viable alternative to traditional exercise.

The Present Study

In the present study, we assess the relationship between housework frequency and skill levels in adolescence. We draw on the theory of embodied cognition,which conceptualizes cognitive development as deeply rooted in sensorimotor interaction with the environment —as discussed in the literature review. This perspective frames housework not merely as a time-use variable, but as a set of embodied routines through which adolescents may acquire or reinforce both physical and cognitive skills in meaningful, real-world contexts. We use simple, random-effect, and fixed-effect regression modeling on a large longitudinal dataset from Hungary.

Our research contributes to the literature in several ways. It examines the frequency of housework on a country-scale dataset rich in variables, allowing us to control for a wide range of individual characteristics and investigate fitness, as well as literacy and mathematics. We discuss the relationship between fitness and housework, which is an under-researched topic. Our results add a new geographical-cultural perspective as well: to our knowledge, this is the first study to extend the discussion to a European context. Hungary is a post-socialist country, formerly part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; its education system shares common roots with neighboring countries, including Austria, Slovakia, Romania, and the Czech Republic. This allows for some generalization of our findings within the Central and Eastern European region. Finally, as we know, this is the only study to examine the effects of housework in a longitudinal study that exploits the longitudinal nature of the data in its methodology, after Keane et al. (2022), who applied this kind of methodology in a very different context (data from Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam). While our study does not claim to establish causality, its design goes a step beyond most previous research by leveraging panel data and applying fixed effects models. This way, we account for all time-invariant individual characteristics that could confound the relationship between housework and skill development. This approach reduces bias compared to earlier work, which typically employs cross-sectional designs or simpler longitudinal models (Wooldridge, 2010). However, time-varying unobserved confounders, as well as sample selection, may still bias our estimates; therefore, we view our findings as indicative of robust associations rather than definitive causal effects.

Hypotheses

Three research questions and related hypotheses are considered in this paper.

•(RQ1) How does the frequency of housework predict literacy and numeracy skill levels in Grades 6, 8, and 10?

(H1) It is difficult to develop a hypothesis on the effects of housework based on the mixed findings in the literature, with no prior research from European countries that could serve as reference points. Nevertheless, we anticipate a U-shaped relationship between the frequency of housework and educational development. This hypothesis is predicated on the assumption that, in moderate quantities, housework can work as a fertile ground for embodied learning, bolstering cognitive skill development, whereas excessive involvement could detract from time spent on educational pursuits and other, perhaps more effective forms of learning. This hypothesis is consistent with the positive effects of housework participation found by Zhang and Ye (2024) and the negative effects found by Sharma and Shah (2025), and the time substitution patterns found by Tan et al. (2023) and Keane et al. (2022).

•(RQ2) How does the frequency of housework predict the level of fitness skills in Grades 6, 8, and 10?

(H2) Based on the findings of Tanucan et al. (2022), we hypothesize that fitness skills among children who spend some time doing housework should, on average, improve more than among children who do not participate in housework. This effect, however, might be very small, as housework is usually not supervised by professionals (as was the case in Tanucan et al.’s (2022) study).

•(RQ3) Are these effects heterogeneous with respect to gender, parental education, or mother’s labor market status?

(H3) We do not expect to observe heterogeneity in the effects. Our assumption is that unequal exposure, if present, results from an unequal distribution of household chores, not a differential impact on different subgroups. While Sharma and Shah (2025) did find heterogeneous effects between boys and girls in India, Telzer and Fuligni(2009) and Tepper et al. (2022) find no such effects in the culturally somewhat less distant United States and Australia.

Methodology

Research Design

This study follows a panel design to examine the relationship between adolescents’ involvement in housework and their skill development over time. We combine data from the National Assessment of Basic Competencies (NABC) and the NETFIT physical fitness database to construct a panel of 37,461 students observed in Grades 6, 8, and 10. Fixed-effects linear regressions are used to estimate within-student associations (accounting for time-invariant confounding). Pooled OLS and random-effects model estimates are included for comparison.

The sample includes 37,461 adolescents from Hungary who participated in the National Assessment of Basic Competencies (NABC), a standardized test that assesses numeracy and literacy competence among all students in Hungary. It is accompanied by a background questionnaire for students and their families. It is methodologically similar to the PISA tests and mandatory for all students in the 6th, 8th, and 10th grades, with no re-take tests offered. These tests are considered low-stakes for students and high-stakes for schools, as they are primarily used by the government to evaluate the performance of institutions. The NABC was first introduced in 2001 and has been used nationwide since 2008, with its competence scores consistently and comparably across different grades and assessment years since 2010.

The NABC data is linked to two other data sources: the Hungarian National Fitness Assessment (NETFIT) database (see Csányi et al., 2015), which contains data from a comprehensive fitness testing program that assesses the physical fitness of students in public education; and a Complex Regional Development indicator (see Institute for Economic and Enterprise Research, 2019), a composite index used to evaluate the development level of LAU1 microregions (“járások,” or districts). It is a weighted average of indicators of living conditions, the local economy, the labor market, infrastructure, and the environment.

Sample

We restricted the whole linked NABC sample (87,158 6th-grade students in 2017) to those who took the reading literacy test, the mathematics competence test, and the NETFIT fitness test in 2021 (-31,743 students) and answered the question on the frequency of housework on the student background questionnaire in 2017 and 2019 (-17,954 students). The final sample consists of 37,461 students. There are four primary reasons for these high levels of missingness. First, some students dropped out of school by the spring of 2021, as by this time, they had passed the compulsory schooling age of 16 in Hungary. Second, student background questionnaires (where the housework questions are asked) are completed on a voluntary basis (with a pre-pandemic questionnaire response rate of ~80%), with the option of skipping questions. Third, while the NABC tests are administered on the same day, the NETFIT tests are conducted separately. Consequently, with no retake tests offered, some students completed only one of the two tests, resulting in further missing data. Fourth, the percentage of missing students was exceptionally high in 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to these effects, missingness in the sample is not random and is likely to be influenced by unobserved variables, such as parental attitudes. Modern missing data methods (such as multiple imputation and full information likelihood estimation) were considered to mitigate this issue; however, these methods work optimally when the proportion of missing data is relatively low and the missing at random (MAR) assumption is reasonable. Therefore, we opted for listwise deletion instead, with the addition of detailed sample statistics reported (see Table 1) to orient the reader on how the working sample is distorted from the general population of Hungarian adolescents. Missingness beyond sample selection was addressed with multiple imputation (see Appendix D).

Table 1 presents sample selection statistics. Girls are slightly overrepresented in our sample by +1.2 percentage points. Students in the selected sample were more likely to attend eight-year grammar schools in 2017, which are generally attended by children from high social status families (see e.g., Szabó et al., 2018, p. 40). They are also more likely to have higher-than-average reading literacy and mathematics skills and academic aspirations, and are more likely to have a parent with a higher level of education. They are less likely to go to school in the capital (Budapest), which is primarily due to the high level of missing fitness scores in Budapest in 2021, and are more likely to be in a city or a county seat of a more developed LAU1 region.

Table 1. Sample Selection Statistics

| Full NABC sample | Working sample | |

| 6th-grade skills | ||

| Reading literacy | 500 | 512.9 |

| Mathematics | 500 | 512.5 |

| Fitness | 500 | 500.4 |

| Gender | ||

| Girls | 49.4% | 50.6% |

| Parental education | ||

| ISCED 0–1 | 0.6% | 0.2% |

| ISCED 2 | 8.0% | 4.8% |

| ISCED 3C (vocational) | 3.2% | 2.4% |

| ISCED 3B (vocational with Matura) | 20.5% | 20.4% |

| ISCED 3A (general with Matura) | 30.6% | 33.3% |

| ISCED 5+ | 37.0% | 38.9% |

| School type | ||

| General primary school | 95.6% | 95.1% |

| 8-year grammar school | 4.4% | 4.9% |

| 6th-grade aspirations | ||

| Primary | 1.5% | 0.7% |

| Vocational without Matura | 9.0% | 6.4% |

| Matura | 9.7% | 8.3% |

| Vocational after Matura | 23.4% | 23.7% |

| Tertiary | 56.5% | 60.8% |

| Locality type | ||

| Towns | 24.8% | 24.4% |

| Cities | 40.0% | 42.3% |

| County seats | 19.3% | 20.9% |

| Budapest (capital city) | 15.9% | 12.4% |

| Regional development | ||

| Mean indicator level (the lower the number, the more developed) | 53.48 | 52.23 |

| N | 87158 | 37461 |

Note: The table compares full sample means/ratios to working sample means/ratios to provide an overview of sample selection. Data was taken from the 6th grade (2017), the year with the highest response rate on the background questionnaire. The full NABC sample is essentially population-wide with a low level of random missingness. The working sample and the dropped observations show significant differences in all displayed characteristics (in bold) according to likelihood-ratio chi-squared tests (categorical variables) and two-sample t-tests (continuous variables), except for fitness.

Measure of Housework Frequency

Information on housework frequency was ascertained via the NABC student background questionnaire. Students were asked the following question (originally in Hungarian): How often does the following happen in your family? […] I do housework with my family. Answers were provided on a four-point scale with responses labelled never or almost never, once or twice a month, once or twice a week, and every day or almost every day. Garden chores are addressed in a separate question, so this measure only considers in-house activities. Adolescents’ involvement in housework is not necessarily stable over time: it may change, for example, with age, as traditional shifts in family responsibilities occur as students age, with changes in parental employment, sibling births, or health events. As such, housework frequency is best modeled as a time-varying predictor, capturing within-person changes across different developmental stages. This condition is also pivotal to our use of fixed effects models, which leverage such intra-individual variation to control for time-invariant confounders. Empirically, our measure of housework frequency (ranging from 1 to 4) shows meaningful variation across time and individuals: it has an overall standard deviation of 0.816, with a between-person SD of 0.675 and a within-person SD of 0.458. These values support the decision to treat housework frequency as time-varying and confirm that there is sufficient within-person change for unbiased and efficient estimation with our chosen panel models.

Housework is a multidimensional phenomenon. It could be routine or requested, complex or simple, strenuous or effortless, involving responsibility or risk-free. Due to the constraints of our data source, the scope of this paper is limited to one dimension: frequency. Focusing on this aspect of housework is common in the literature, and conclusions about the importance of housework with respect to skill development are often drawn from some version of this metric (see e.g., Telzer & Fuligni, 2009; Wang et al., 2022; Wolf et al., 2015; Zhang & Ye, 2024). Our measure captures the number of occasions (days) a student participated in housework. A more detailed metric would include the amount of time allocated to housework within a given period (day, week). Still, we deem our measure satisfactory for two reasons. First, some evidence suggests that the act of doing housework on more days better captures the association with cognitive development than the amount of time (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009). Second, this measure allows us to more directly compare our results with studies where the authors used a similar measure of housework frequency, but opted for different statistical methods (Telzer & Fuligni, 2009; Wang et al., 2022).

Measure of Fitness

A measure of fitness was constructed from the linked NETFIT database as the first principal component of nine fitness indicators. This score was then standardized with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100 in the 6th grade prior to sample selection. For more details on the construction of this index, consult Appendix C. As the descriptive statistics in Table 2 indicate, fitness skills decrease between Grades 8 and 10, which could be a result of students having spent more time indoors during the COVID-19 lockdowns.

Measures of Cognitive Skills

Reading literacy (Grades 6, 8, and 10) and mathematics (Grades 6, 8, and 10) measures come from the NABC data (see e.g., Szabó et al., 2018). The test results are comparable across years, as they were standardized on a common scale, with common tasks across grades serving as anchors for comparability. We further standardized mathematics and reading literacy scores with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100 in Grade 6 and applied the same standardization to subsequent years prior to sample selection. As the descriptive statistics presented in Table 2 indicate, cognitive skills developed less between Grades 8 and 10. Boza and Hermann (2023) have shown (for the full sample presented in Table 1) that this observed lower development in students’ skills is not significantly different from that observed in previous years. They also show that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have not yet been detected on the 2021 Grade 10 NABC sample. A likely explanation for this difference in improvement is that skill development tends to follow logistic curves, and these tend to be steeper for most children in the period between Grades 6 and 8 than that between Grades 8 and 10 (see e.g., Molnár & Csapó, 2003).

Table 2. Summary Statistics for Literacy, Mathematics, and Fitness Skill Measures for Students in the Sample

| Skill > Grade (Year) | Mean | Standard deviation | Min. | Max. | N |

| Reading literacy | |||||

| 6 (2017) | 512.9 | 94.32 | 149.4 | 815.5 | 37,382 |

| 8 (2019) | 563.7 | 93.44 | 160.0 | 828.2 | 37,315 |

| 10 (2021) | 583.2 | 93.78 | 188.0 | 841.0 | 37,461 |

| Mathematics | |||||

| 6 (2017) | 512.5 | 94.91 | 180.4 | 898.4 | 37,370 |

| 8 (2019) | 580.6 | 93.06 | 213.7 | 877.8 | 37,295 |

| 10 (2021) | 594.5 | 103.04 | 213.9 | 926.7 | 37,461 |

| Fitness | |||||

| 6 (2017) | 500.4 | 97.27 | -50.6 | 913.2 | 36,127 |

| 8 (2019) | 524.9 | 109.47 | -9.0 | 899.1 | 35,582 |

| 10 (2021) | 517.3 | 114.66 | 80.6 | 965.6 | 37,461 |

Note: The table shows summary statistics for the skills measures for in-sample students. Sample sizes vary due to year-to-year missing observations, except for 2021 (see Sample subsection).

Control Measures

Our statistical models encompass a comprehensive set of control variables, including demographic factors, socioeconomic and household characteristics, attitudes and aspirations, leisure and extracurricular activities, geographical and institutional contexts, as well as school and local area development indicators. For a detailed list of variables, see Appendix B. For a comparison with explanatory variables included in the Zhang and Ye (2024) paper, see Table A1 in Appendix A.

Statistical Models

We employ multiple regression analysis in Stata (version 18) with cluster-robust standard errors. The dependent variables are mathematics, reading literacy, and fitness skills. The primary independent variable is a categorical variable: the frequency of housework. Estimated models include a range of control variables (see Appendix B).

To account for time-period effects (presented in Table 2), year dummies are included in the analysis. Skill levels are also included as controls in each other’s equations to help isolate the unique association between housework frequency and each outcome. However, we recognize that including potentially mediating variables may lead to over-controlling and attenuated estimates. To address this concern, we conducted robustness checks by estimating the models without controlling for the other skill types. These alternative specifications yielded similar patterns of association, suggesting that our main results are not driven by over-adjustment. To assess the potential issue of multicollinearity, we calculated Variance Inflation Factors (VIF) on the full sample for each control variable in our regression models. The VIFs for our main measure, housework frequency, and for the skill controls were all below 2.

Four model specifications are considered for each outcome: (1) a pooled multivariate linear regression model with the following explanatory variables: housework, year, current skill levels, gender, and year dummies; (2) another pooled linear model with all control variables; (3) a random effects model with all controls; and, finally, (4) a fixed effects model with all controls. Models (3) and (4) use information from having repeated measures for each student (see e.g., Cunningham, 2021). While random effects models assume that unobserved individual heterogeneity is uncorrelated with the regressors, fixed effects models allow for this correlation and eliminate all time-invariant confounding through within-transformation. This makes the fixed effects approach more appropriate in our context, where stable but unobserved characteristics—such as parenting styles, household routines, or innate student traits—may influence both the frequency of housework and skill development.

To assess whether the random effects assumptions are tenable, we conducted Hausman’s (1978) specification tests comparing the random effects and fixed effects estimators on the first imputed sample. The tests rejected the null hypothesis of no correlation between the individual effects and the explanatory variables (p < 0.001 in all three cases), suggesting that the random effects estimator is inconsistent. Accordingly, we rely on fixed effects estimates for inference.

Heterogeneous effects are estimated using fixed effects models on subsamples. These models are limited to samples where the splitting variables (between which the heterogeneity is tested, i.e., gender, parental education, and parental labor market status) are non-missing. This is necessary to maintain the same number of observations for each imputed dataset and ensure the results can be combined using Rubin’s rule (Rubin, 1987).

Results

Main Results: Housework and Skill Development

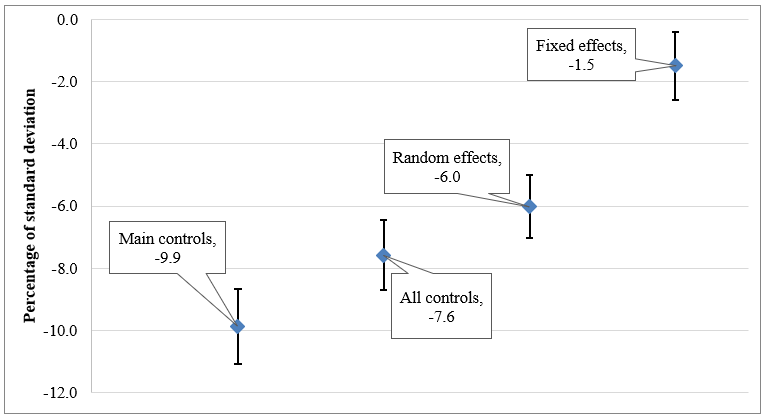

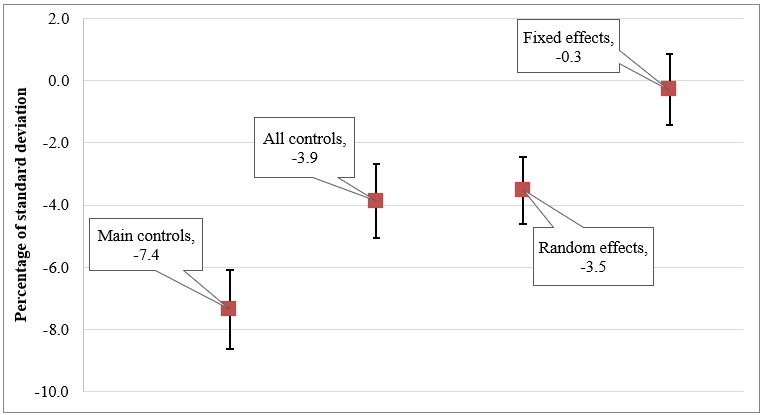

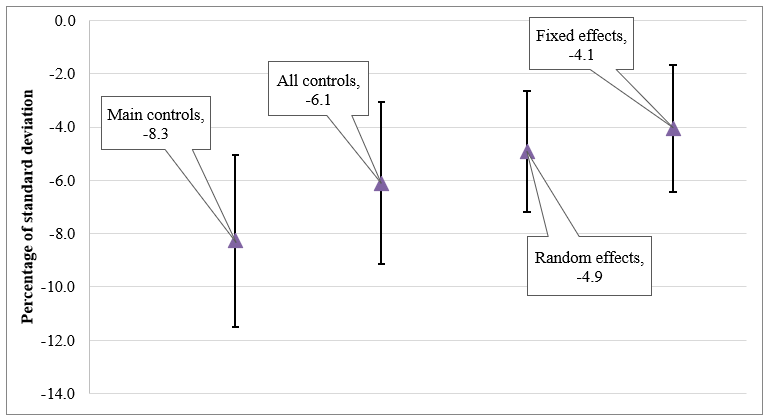

Multiple regression estimates for the relationship between housework frequency and other factors on adolescents’ skills are presented in Tables 3–5, and visually depicted in Figures 1–3. When interpreting the estimates, we classify them using education-specific guidelines derived from the works of Hill et al. (2008) and Kraft (2020): values smaller than 5 points (< .05SD) are labelled small, values between 5 and 20 points (.05–.20 SD) are considered moderate, and effect sizes over 20 points (≥ .20SD) are large.

Gender disparities were evident across subjects, with boy students demonstrating a disadvantage in literacy, a similar level advantage in mathematics, and an even higher advantage in fitness. The advantage in fitness was very high: around 85% of the full sixth-grade sample’s standard deviation.

The pooled and random effects models suggest that increased engagement in housework, particularly “every day or almost every day,” is moderately negatively associated with literacy and mathematics skills (in the baseline model: -.099SD,p< .01 for literacy; -.074SD,p< .01 for mathematics). In the pooled model, the estimated literacy effects of doing housework this often were similar in magnitude to the effect of having a highly educated parent (master's level or higher). This is consistent with the idea that extensive domestic responsibilities detract from students’ ability to excel in these domains. However, as individual fixed effects were introduced to the model, this relationship shrank in magnitude. For mathematics, the effect became insignificant even at a 10% level of significance. For reading literacy, it stayed significant statistically (-.015 SD, p< 0.01) but lost all practical significance: the effect size ended up being (very) small, less than 1.5% of the full 6th grade sample’s standard deviation. Therefore, if controlled for time-invariant, unobserved characteristics, the seemingly negative effect of housework diminishes and practically becomes zero.

In contrast to the other two domains, participation in housework had a clear, albeit practically small, effect on fitness. Not doing any housework at all (or almost ever) was significantly associated with a 4.05% (6th grade) standard deviation decrease in fitness compared to housework once or twice a month, even after controlling for all control variables and time-invariant effects. This implies that engaging in household tasks to some extent could contribute to or at least reflect a lifestyle that supports physical well-being. This also supports the findings of Tanucan et al. (2022), who suggest that housework is a potential area for fitness development, and housework-based exercise could be considered a valuable tool in health and fitness education.

Taken together, the estimates reported in Tables 3–5 (visualized in Figures 1–3) indicate that the apparent moderate, negative association between very frequent housework and adolescents’ literacy and mathematics achievement largely reflects time-invariant confounding. Once individual fixed effects were introduced, the coefficient for literacy contracted to -.015 SD (p< .01) and became statistically indistinguishable from zero for mathematics, reducing both findings below any threshold of practical importance. By contrast, the fitness penalty associated with performing no household tasks was close to moderate (-0.04SD, p< .01) even in the fixed effects model, suggesting that a minimal level of chore participation is linked to better physical conditioning. To sum up, after accounting for stable, unobserved heterogeneity, extensive domestic responsibilities do not meaningfully hamper academic skills, whereas complete disengagement from household work is modestly detrimental to physical fitness.

Figure 1. Coefficient Plot: Estimated Effect of Daily or Almost Daily Housework on Literacy in Four Statistical Models (% of 6th Grade Standard Deviation)

Figure 2. Coefficient Plot: Estimated Effect of Daily or Almost Daily Housework on Mathematics in Four Statistical Models (% of 6th Grade Standard Deviation)

Figure 3. Coefficient Plot: Estimated Effect of ‘Never or almost never’ Doing Housework on Fitness in Four Statistical Models (% of 6th Grade Standard Deviation)

Table 3. Regression Models: Reading Literacy on Housework Frequency and Control Variables

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Lin. reg., no extra controls | Lin. reg.+ all controls | Random effects+ all controls | Fixed effects+ all controls | |

| Housework | ||||

| Never or almost never | 0.21 | 1.93* | 1.70* | 1.34 |

| (1.033) | (0.968) | (0.839) | (0.870) | |

| Once or twice a week | -1.82** | -2.92** | -2.27** | -0.47 |

| (0.522) | (0.484) | (0.427) | (0.455) | |

| Every day or almost every day | -9.88** | -7.58** | -6.02** | -1.49** |

| (0.618) | (0.577) | (0.516) | (0.564) | |

| Mathematics | 0.71** | 0.58** | 0.50** | 0.27** |

| (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Fitness | 0.04** | 0.02** | 0.03** | 0.04** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Year: 2019 | 1.15** | 10.13** | 15.23** | 31.56** |

| (0.374) | (0.429) | (0.398) | (0.437) | |

| Year: 2021 | 11.21** | 25.65** | 30.41** | 49.35** |

| (0.406) | (0.655) | (0.582) | (0.643) | |

| Gender (boy) | -32.24** | -14.76** | -19.19** | N/A |

| (0.537) | (0.531) | (0.539) | ||

| Observations | 112383 | 112383 | 112383 | 112383 |

| Maximum fraction of missing information | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.21 |

| Minimum R^2 | 0.62 | 0.67 | ||

| Maximum R^2 | 0.62 | 0.67 | ||

| Required number of imputations | 3.00 | 57.00 | 42.00 | 15.00 |

Note: Each column presents estimates from a different specification. Cluster-robust standard errors are in parentheses. The table presents aggregated estimates for 100 regression models on multiple imputed datasets, explaining 10th/8th/6th-grade skill levels in terms of frequency of housework, skills, gender, and other factors. The required minimum number of imputations was estimated based on von Hippel’s formula (von Hippel, 2020). Note that skill levels were standardized on a common scale with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100 in the 6th grade. Thus, for example, a coefficient of ±5 corresponds to a ±5%SDdifference. Each column corresponds to a different model, with outcomes displayed in the headings. The baseline for housework frequency is “once or twice a month.” Model (1) only contains the displayed variables, while models (2) to (4) consist of controls for socioeconomic and household background, attitudes and aspirations, extracurricular activities, and geographical and institutional context, all suppressed for the sake of brevity. For more information on control variables, see Section 3.*p< .05,**p< .01

Table 4. Regression Models: Mathematics on Housework Frequency and Control Variables

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Lin. reg., no extra controls | Lin. reg. + all controls | Random effects + all controls | Fixed effects + all controls | |

| Housework | ||||

| Never or almost never | -4.98** | -3.98** | -2.78** | -1.41 |

| (1.070) | (0.981) | (0.855) | (0.885) | |

| Once or twice a week | -1.66** | -1.57** | -1.32** | 0.01 |

| (0.554) | (0.512) | (0.449) | (0.460) | |

| Every day or almost every day | -7.35** | -3.87** | -3.53** | -0.29 |

| (0.648) | (0.609) | (0.544) | (0.580) | |

| Literacy | 0.77** | 0.62** | 0.54** | 0.29** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| Fitness | 0.07** | 0.03** | 0.03** | 0.03** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | |

| Year: 2019 | 27.49** | 34.97** | 39.14** | 53.41** |

| (0.378) | (0.446) | (0.400) | (0.407) | |

| Year: 2021 | 27.13** | 44.26** | 50.20** | 69.34** |

| (0.413) | (0.711) | (0.610) | (0.627) | |

| Gender (boy) | 22.24** | 20.00** | 21.10** | N/A |

| (0.563) | (0.539) | (0.551) | ||

| Observations | 112383 | 112383 | 112383 | 112383 |

| Maximum fraction of missing information | 0.09 | 0.38 | 0.35 | 0.25 |

| Minimum R^2 | 0.63 | 0.68 | ||

| Maximum R^2 | 0.63 | 0.69 | ||

| Required number of imputations | 4.00 | 42.00 | 36.00 | 20.00 |

Note: Each column presents estimates from a different specification. Cluster-robust standard errors are in parentheses. The table presents aggregated estimates for 100 regression models on multiple imputed datasets, explaining 10th/8th/6th-grade skill levels in terms of frequency of housework, skills, gender, and other factors. The required minimum number of imputations was estimated based on von Hippel’s formula (von Hippel, 2020). Note that skill levels were standardized on a common scale with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100 in the 6th grade. Thus, for example, a coefficient of ±5 corresponds to a ±5%SDdifference. Each column corresponds to a different model, with outcomes displayed in the headings. The baseline for housework frequency is “once or twice a month.” Model (1) only contains the displayed variables, while models (2) to (4) consist of controls for socioeconomic and household background, attitudes and aspirations, extracurricular activities, and geographical and institutional context, all suppressed for the sake of brevity. For more information on control variables, see Section 3.*p< .05,**p< .01

Table 5. Regression Models: Fitness on Housework Frequency and Control Variables

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Lin. reg., no extra controls | Lin. reg. + all controls | Random effects + all controls | Fixed effects + all controls | |

| Housework | ||||

| Never or almost never | -8.27** | -6.10** | -4.91** | -4.05** |

| (1.649) | (1.545) | (1.155) | (1.213) | |

| Once or twice a week | 4.58** | 3.18** | 1.56** | 0.92 |

| (0.877) | (0.808) | (0.602) | (0.637) | |

| Every day or almost every day | 1.26 | 1.72 | 1.01 | 1.15 |

| (1.031) | (0.980) | (0.735) | (0.794) | |

| Literacy | 0.10** | 0.05** | 0.08** | 0.08** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.005) | |

| Mathematics | 0.16** | 0.07** | 0.07** | 0.05** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.005) | |

| Year: 2019 | 8.83** | 15.73** | 14.38** | 16.07** |

| (0.472) | (0.553) | (0.486) | (0.563) | |

| Year: 2021 | -3.04** | 13.48** | 6.28** | 6.01** |

| (0.621) | (1.004) | (0.841) | (0.945) | |

| Gender (boy) | 85.23** | 83.26** | 84.09** | N/A |

| (0.894) | (0.895) | (0.888) | ||

| Observations | 112383 | 112383 | 112383 | 112383 |

| Maximum fraction of missing information | 0.12 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Minimum R^2 | 0.21 | 0.28 | ||

| Maximum R^2 | 0.21 | 0.28 | ||

| Required number of imputations | 6.00 | 11.00 | 21.00 | 20.00 |

Note: Each column presents estimates from a different specification. Cluster-robust standard errors are in parentheses. The table presents aggregated estimates for 100 regression models on multiple imputed datasets, explaining 10th/8th/6th grade skill levels in terms of frequency of housework, skills, gender, and other factors. The required minimum number of imputations was estimated based on von Hippel’s formula (von Hippel, 2020). Note that skill levels were standardized on a common scale with a mean of 500 and a standard deviation of 100 in the 6th grade. Thus, for example, a coefficient of ±5 corresponds to a ±5%SDdifference. Each column corresponds to a different model, with outcomes displayed in the headings. The baseline for housework frequency is “once or twice a month.” Model (1) only contains the displayed variables, while models (2) to (4) consist of controls for socioeconomic and household background, attitudes and aspirations, extracurricular activities, and geographical and institutional context, all suppressed for the sake of brevity. For more information on control variables, see Section 3.*p< .05,**p< .01

Heterogeneity

Our investigation into whether the effects of housework on educational development are influenced by gender, mother’s labor market status, and parental education helped us outline some groups for whom the association could be both statistically and practically significant. Table 6 contains all significant estimates that are classified as moderate or high based on our effect size classification rules introduced at the beginning of the Results section. More detailed regression tables for the heterogeneity tests are included in Appendix A.

We observed significant but small gender-based heterogeneity. Girls who do housework at least once or twice a week had, on average, lower literary skills ceteris paribus than girls who do housework less frequently (weekly: -.016SD, p< .05; daily: -.024SD, p< .01). This association was not present in the boys’ sample.

We only found parental education-based heterogeneity for students with tertiary-educated parents. These adolescents had lower fitness scores on average if they “never or almost never” do housework (-.055 SD, p < .01), and slightly higher scores if they answered “every day or almost every day” (.028 SD, p < .05). However, children of these highly educated parents who worked around the house often were also ceteris paribus slightly worse readers (-.031SD, p< .01).

The frequency of housework carries different developmental implications depending on the mother’s labor market status. We observed substantial heterogeneity for students with unemployed or only occasionally working mothers (not on parental benefits), who displayed much lower mathematics skills if they (almost) never do housework (-.191SD, p< .05). Meanwhile, students whose mothers receive parental benefits (i.e., childcare duties subsidized by the government) also had lower mathematics scores if they do housework (almost) every day (-.104SD, p< .05). Additionally, literacy skills of adolescents whose mothers have permanent jobs were ceteris paribus slightly lower if they do housework every day or almost every day. They also had slightly lower fitness scores if they did (almost) no housework.

Table 6. Summary Table for Moderate or High, Significant Heterogeneous Effects

| Subgroup | Domain | Housework Frequency | β | p |

| Mother’s Labor Market Status | ||||

| Unemployed or casual worker | Mathematics | Never/almost never | -19.08 | <.05 |

| On parental benefits | Mathematics | Daily/almost daily | -10.37 | <.05 |

| Parental Education | ||||

| Tertiary | Fitness | Never/almost never | -5.47 | <.01 |

| Gender x Parental Education x Employment | ||||

| Girls, tertiary-educated parents, working mothers | Literacy | Daily/almost daily | -5.55 | <.01 |

| Girls, tertiary-educated parents, working mothers | Fitness | Never/almost never | -5.47 | <.01 |

Note. The table summarizes statistically significant moderate or high subgroup-specific effects from fixed effects regressions examining the association between housework frequency and adolescents’ standardized outcomes in reading literacy, mathematics, and fitness. Dashed lines separate estimates from different regression models estimated for the defined subgroups (e.g., girls only, students with tertiary-educated parents, etc.). Coefficients (β) are within-student fixed-effects estimates expressed in the original vertically scaled metric, where all outcomes are standardized to a mean of 500 and a standard deviation (SD) of 100 in Grade 6; hence,5 points equal 0.05 SD. We classify effects using education-specific guidelines drawn from Hill et al. (2008) and Kraft (2020): values between 5 and 20 points (0.05–0.20 SD) are considered moderate, and values of 20 points or more (≥ 0.20 SD) would be considered large—none in this table reach that threshold. Typical two-year gains in the present sample are about 51 points in literacy, 68 in mathematics, and 25 in fitness (see Table 2), so the largest coefficient shown here,-19.08 points for mathematics among students with unemployed mothers who never do housework, represents roughly 28 percent of the average two-year mathematics gain.

Finally, girls with tertiary-educated parents and with a mother in a permanent job had, on average, slightly lower literacy scores if they do housework once or twice a week (-.031 SD, p< .05). This negative association was stronger for those who do housework every day or almost every day (-.056 SD, p< .01). Table A11 shows comparison estimates that help us put these results into perspective. Among other girls, no significant differences were observed, except for those who engage in housework daily, who also had ceteris paribus lower literacy skills (-.014 SD, p< .05), albeit this statistical effect was very small. Meanwhile, boys with tertiary-educated parents and with a mother in a permanent job did not show a statistically significant relationship between housework and literacy skills. These findings suggest that frequent engagement in household tasks is particularly associated with lower literacy outcomes for girls in highly educated families with working mothers, while girls in different households and boys in similar households do not appear to be affected to the same extent.

Discussion

Our findings differ from most previous studies that reported either negative associations (e.g., Sharma & Shah, 2025; Wolf et al., 2015) or modest positive effects (e.g., Tepper et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022; Zhang & Ye, 2024), in that we observed no meaningful relationship between housework frequency and educational achievement in the general student population. One likely reason for this discrepancy is our methodological approach; studies that use comparable methods report findings most consistent with ours (Keane et al., 2022;Telzer & Fuligni, 2009). Therefore, our hypothesis that moderate levels of housework enhance cognitive skills (H1) must be rejected, as the data reveal no meaningful positive relationship.

However, a U-shaped effect is a plausible theory for the underlying relationship between a broader concept of housework and skill development. Our measure of housework frequency likely masks a mix of different kinds of chores—some that might help students learn new skills, and others that simply take up their time without educational benefits. When these very different tasks are grouped together, their positive and negative effects could cancel each other out. This would mean that the expected pattern is only captured by the frequency of selected types of housework, as cooking meals, grocery shopping, or planning household budgets, rather than simpler tasks like washing dishes, vacuuming, or folding laundry. Tan et al. (2023) identify such patterns for more complex, more demanding tasks in Zambia.

In line with the findings of Tanucan et al. (2022, 2024), we hypothesized that children who participate more frequently in housework would demonstrate greater improvements in fitness skills (H2). Our analysis confirmed this hypothesis, showing that children who either never or rarely engage in housework exhibited lower fitness skills, even after controlling for individual fixed effects. This suggests that participating in household tasks, even to a limited extent, may foster or reflect a lifestyle that supports physical well-being. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is supported by our results.

We also hypothesized that the effects of housework on skill development would not vary according to gender, parental education, or maternal employment status (H3). However, our findings revealed some heterogeneity. The most pronounced effects were observed in relation to maternal employment status. Firstly, students from households where the mother is unemployed or only engaged in casual work showed lower mathematics scores if they (almost) never do housework. One possible explanation for this is that, on average, children from economically less stable households experience less structured and supportive learning environments (Garrett-Peters et al., 2016; Hanscombe et al., 2011). This could contribute to lower mathematics skills (Daucourt et al., 2021) if the children themselves do not participate in household chores and organize the home environment to make it less chaotic and more suitable for learning (Hanscombe et al., 2011). Secondly, students from households where mothers receive parental benefits showed worse mathematics outcomes when they engage in housework (almost) daily. These families with mothers who receive childcare benefits have more time to invest in their children’s home surroundings,and thus are better positioned to provide a supportive learning environment(Houmark et al., 2024; Kozak et al., 2021). However, when these children are expected to shoulder housework duties almost every day, the added burden is likely to crowd out homework and numeracy-rich parent-child interactions, cancelling the potential gains of an otherwise supportive home environment (Keane et al., 2022; Tan et al., 2023)

Parental education also moderated some of these relationships. Adolescents with tertiary-educated parents showed slightly higher fitness scores when frequently engaging in housework but worse reading outcomes. This may also be attributed to differences in home environments: highly educated families are more likely to offer the necessary resources for effective learning (Dong et al., 2020; Merz et al., 2014), making housework a distraction rather than a productive activity.

Finally, we also detected some gender-based heterogeneity, particularly for girls in highly educated households with stable maternal employment status. In these households, both moderate and frequent engagement in housework was associated with lower literacy skills. Here, a likely mechanism is a gendered time-trade-off: when mothers work long and stable hours, daughters, but not sons, are expected to shoulder a disproportionate share of routine domestic chores (Gracia et al.,2021; Lam et al., 2016) — i.e., having to do more tasks each time they do housework. Because high-SES families supply abundant literacy materials and the marginal payoff of each additional hour of leisure reading is largest in such resource-rich contexts (Chiu & McBride-Chang, 2010; Hemmerecht et al., 2017), the lost reading time hurts these girls’ literacy more than it hurts their brothers, or girls from lower-resource homes.

These findings suggest that, while housework does not have a universal effect on skill development, its associations vary across different socioeconomic contexts that influence the learning environment. Consequently, our third hypothesis is rejected.

Conclusion

We concluded that household responsibilities have a limited impact on educational achievement when accounting for individual fixed effects. Frequent engagement in housework is associated with slightly lower mathematics skills. The effect is minor and unlikely to be of practical significance. At the same time, even minimal participation in household tasks appears to support physical well-being, as children who never or almost never engage in housework tend to have lower fitness skills, even if individual fixed effects are controlled for. This relationship between housework and skills varies across socioeconomic contexts, particularly in relation to maternal employment status and parental education. The most notable difference is that children in households where the mother is unemployed or engaged in casual work show much lower mathematics scores if they rarely do housework, while those whose mothers receive parental benefits have worse mathematics outcomes when they engage in housework daily.

Recommendations

Recommendations for Parents and Educators

We offer the following cautious recommendations for parents and educators:

Support at least some engagement in housework to promote physical well-being. We estimated that even minimal participation in household tasks was associated with higher fitness skills. Children who never or almost never do housework consistently showed lower fitness outcomes, suggesting that helping at home may contribute to a fitter lifestyle.

Avoid overloading children with daily chores. While very frequent involvement in household tasks (e.g., daily or almost daily) was linked to slightly lower mathematics scores, this effect was small and likely not meaningful in practice. On the other hand, this very frequent involvement had no positive effects either. Assigning modest, manageable responsibilities is probably the best way to balance the benefits of housework with the need to protect time for study and rest.

Don’t assume that housework is inherently beneficial for academic outcomes. Our results do not support the idea that any level of housework would improve school performance across the board. It is likely that different types of tasks have different cognitive or educational value, and further research that distinguishes task types would be helpful, but until then, it is advisable not to frame housework as a learning device.

Pay attention to the family environment. We found that the relationship between housework and academic outcomes varies by maternal employment and parental education. These patterns likely reflect differences in how families structure time, distribute responsibilities, and support learning at home. Educators should interpret the role of housework in light of these broader household conditions, rather than assuming uniform effects across all students.

Finally, we emphasize that these recommendations are based on data from Hungarian adolescents and may not generalize to other cultural or institutional contexts without critical reflection.

Recommendations for Research

Future research should examine how cultural and national differences influence the relationship between housework and adolescent skill development. While the frequency of housework does not appear to affect cognitive skills in the general adolescent population, its varying effects across socioeconomic and gender subgroups suggest that sociocultural and institutional factors may play a role.

Special attention should be paid to the role of parental involvement. In member countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), most parents are heavily involved in their children’s education regardless of socio-economic status (Hartas, 2015), suggesting that the difference between the typical parenting of poor and wealthier children is not only in the amount of but also the quality of support. With respect to housework, this quality could be the nature of assigned housework tasks (complexity, physical demands, level of responsibility), or the type of parental guidance and supervision provided.

The gendered dimension of housework requires further exploration, particularly given the finding that frequent housework is linked to lower literacy skills among girls in highly educated households with working mothers. Understanding whether this effect stems from time constraints, competing responsibilities, or other social factors could inform policies aimed at equitable distribution of household labor. More extensive longitudinal studies could also investigate whether these disparities persist into adulthood, potentially influencing academic and career trajectories.

Similarly, the role of maternal employment in shaping the effects of housework should be investigated further, as this study found substantial heterogeneity in housework effects based on mothers' labor market status. Future research should investigate how maternal employment interacts with household responsibilities to clarify what changes in the home learning environment cause these heterogeneous effects.

Future research should also prioritize longitudinal designs that exploit within-subject variation, reducing bias in estimating the true effects of housework. This study's use of repeated measures and fixed-effects models allowed for more accurate estimates by controlling for time-invariant individual differences. Prior studies that relied on cross-sectional designs may have been biased by unobserved individual characteristics that remained constant over time. Furthermore, opting for experimental or quasi-experimental approaches, such as randomized interventions or natural experiments, could strengthen causal inference in this topic.

Finally, we suggest that future work should converge on a unified metric for adolescent housework, allowing findings to be meaningfully compared across studies. We recommend a dual-track measure with (a) an occasion-frequency item with harmonized ordinal categories (structurally similar to the one used in the current paper), and (b) a time allocation measure with a short, validated 24-hour recall module covering routine chores, and more complex domestic work separately. Using a common template like this would eliminate a major source of cross-study heterogeneity and facilitate meta-analytic synthesis.

Limitations

First, the geographical and cultural homogeneity of our sample limits the generalizability of our findings to other contexts. Cultural norms and institutions in Hungary may differ significantly from those in other countries, potentially influencing the relationship between housework and skill development in ways that are not captured in this study.

Second, our measurement of housework frequency is based on adolescents’ self-reports, which are inherently susceptible to reporting bias. Furthermore, the questionnaires specifically ask about housework done collaboratively or concurrently with family members, which may not encompass all types of household duties. This presents both limitations and benefits. On the one hand, whether a child considers a task as “done with others” can vary across families and be influenced by cultural norms, family structure, and the availability of family members for joint activities. This definition also excludes children who serve as primary housekeepers and those in extremely individualized households, where members often work independently around the house. It also constrains the comparability of our findings with studies that either do not differentiate between types of housework or consider housework in a broader, more individualized context. On the other hand, collaborative housework implies some family interaction and teamwork in the process. Parental supervision and family collaboration could provide a context for development and an opportunity to transfer values, attitudes, and skills, such as communication, problem-solving, and cooperation. In this sense, the type of housework identified by the questionnaire should be more effective for skill development (at least for some skills) than other forms of housework.

Third, we only measure housework frequency and do not have information on other aspects of housework, such as the type, complexity, routineness, level of responsibility, or level of annoyance associated with the tasks. While the literature often focuses on frequency (see e.g., Telzer & Fuligni, 2009; Wang et al., 2022; Wolf et al., 2015; Zhang & Ye, 2024), examining other aspects would allow for broader conclusions on the effects of housework as a general concept. In this paper, we could only form conclusions about the frequency of housework with no other restrictions on the tasks and the adolescents’ mindset. Additionally, this measure did not allow for the estimation of time-substitution effects, blocking a more nuanced view on how time spent on housework affects skill development (such as in Keane et al., 2022).

Fourth, while our models include a rich set of time-varying controls — covering household composition, socioeconomic status, educational aspirations, extracurricular activities, and regional context — some relevant factors remain unobserved. These omitted variables may introduce bias even in the fixed effects specification, which controls for time-invariant unobservables. For instance, changes in family functioning or stress levels (e.g., divorce proceedings, chronic illness of a caregiver, or increased financial strain) may simultaneously affect both the adolescent’s housework burden and their academic or fitness performance, yet are not captured in our dataset. Likewise, fluctuations in parental supervision, temporary caregiving responsibilities for younger siblings, or intensive exam preparation periods may influence both skill development and time spent on domestic chores, but these factors remain unmeasured. While our use of panel data and fixed effects models represents methodological improvement over prior research that primarily employs cross-sectional or simpler longitudinal methods, we cannot rule out bias from these unobserved time-varying shocks. As such, while fixed effects models improve internal validity by accounting for all stable individual characteristics (Angrist & Pischke, 2009; Wooldridge, 2010), our findings must be interpreted as robust within-person associations rather than definitive causal effects.

Finally, while multiple imputation techniques were employed to address missing data in the working sample, the prior selection of the working sample (from 87,158 to 37,461 students) via listwise deletion poses limitations. Listwise deletion was necessary because the missing at random (MAR) assumption could not be confidently upheld. As Table 1 demonstrates, the working sample overrepresents students from higher social status backgrounds, those attending eight-year grammar schools, students with higher-than-average reading and mathematics skills, and students who are academically motivated. The bias is most substantial for students with low-educated parents (ISCED 3C or lower). It also underrepresents students from Budapest and those from less developed microregions. This limits the generalizability of our results, particularly regarding lower-SES populations, whose experiences with housework, school engagement, and academic development may systematically differ from those retained in the analytic sample. Estimates of average effects should thus be interpreted as reflecting more advantaged strata of the student population. This is especially relevant considering our finding that parental education-based heterogeneity was only detectable among adolescents with tertiary-educated parents, raising the possibility that important variation among lower-SES groups was obscured by selective attrition.

Ethics Statements

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Szeged (https://u-szeged.hu/english/education-210413/code-of-ethics-of-the).

Funding

This study is supported by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences Research Program for Public Education Development grant (KOZOKT2021-16) and the Government Guarantee Fund (2020-2.1.1-ED-2023-00277) for HORIZON-CL2-2023-TRANSFORMATIONS-01-06.

Generative AI Statement

As the author(s) of this work, we used the AI tools ChatGPT 4o and 4.5 for the purpose of eliminating semantic errors and correcting punctuation. While using this tool, we disallowed the option that permits OpenAI (the company behind ChatGPT) to use the text in the training of generative AI models. After using this AI tool, we reviewed and verified the final version of our work. We, as the author(s), take full responsibility for the content of our published work.