Introduction

Over recent decades, comprehensive sexuality education (CSE) has gained prominence as a vital educational approach globally (Leung et al., 2019). As defined by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), CSE encompasses a rights-based, evidence-based, and age-appropriate program that covers a wide range of themes (UNESCO et al., 2018). In the recent academic and policy literature, the term “sexuality education” is often used interchangeably with CSE and is regarded as a broader umbrella term covering the principles and scope of CSE (UNESCO et al., 2018). For terminological consistency and clarity, the term “sexuality education” is primarily used throughout this paper to reflect the inclusive perspective.

Sexuality education, as one of the effective tools for preventing and addressing the growing global issues such as gender equality, sexual health, and gender-based violence, is receiving growing attention globally (Chavula et al., 2022; Schneider & Hirsch,2018), delivered through variety of channels including schools, communities, peers, and online platforms (Chan et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2023). Although there are some differences in facilitation strategies and the effectiveness of sexuality education across regions due to multiple reasons including political, economic, religious, cultural and customary factors, most countries acknowledge its benefits across age and gender (United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], World Health Organization [WHO] et al., 2020). Meanwhile, international organizations such as WHO and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) have actively pushed for stronger sexuality education to tackle the challenges of child sexual abuse (CSA), gender inequality, sexually transmitted infections, and other sexuality-related issues throughout the globe (Federal Centre for Health Education, 2010; Ketting & Ivanova, 2018a; UNESCO et al., 2018).

Despite the increasing recognition of its role, there remains no globally standardized approaches for sexuality education because of the differences in national contexts, social backgrounds, and educational needs (Haberland & Rogow, 2015). Given the widespread and authoritative of UNESCO, this study adopts the domains of sexuality education from its international guidance (ITGSE), encompassing: (a) Relationships; (b) Values, Rights, Culture and Sexuality; (c) Understanding Gender; (d) Violence and Staying Safety; (e) Skills for Health and Well-Being; (f) The Human Body and Development; (g) Sex and SexualBehaviour; and 8) Sexual and Reproductive Health (UNFPA & UNESCO, 2022;UNESCOet al., 2018).

It is internationally acknowledged that the great value of sexuality education for children in various documents (Council of Europe, 2020;Federal Centre for Health Education, 2010; UNESCO, 2015; UNESCO et al., 2018). Despite the fact that many people think that sexuality is far away from children, UNESCO (2015) reports that sufficient and accurate sexuality education increase children’s vulnerability to sexual abuse and unwise decision-making. While concerns persist that early sexual knowledge may be dangerous, studies indicate that sexuality education is possible and should start in early childhood, emphasizing the necessity of initiating it at an early age (Breuner & Mattson, 2016).

Despite the widely acknowledged value of sexuality education for children, its implementation across the globe varies significantly (UNESCO, 2021). There are marked differences across countries and regions in terms of the extent of implementation, quality, policies, and practical content. In countries like Sweden and the Netherlands, sexuality education has been introduced from early childhood, along with well-established practice guidelines and policy support for both professionals and parents (Ketting & Ivanova, 2018a, 2018b). In contrast, some countries in the Middle East, Africa and Asia, show weak popularity (Achoraet al., 2018; Jeong et al., 2023; Mertoğlu, 2019). Despite recent efforts to develop sexuality education programs, implementation remains inconsistent across Asia due to cultural and religious factors. For example, in Malaysia, sexuality education has been introduced under the Reproductive Health and Social Education (PEERS) curriculum since 2006, but remains limited in scope due to social and cultural sensitivities (Mokhtar et al., 2013; UNFPA, UNESCO, et al., 2020). Similarly, in China, it is not a compulsory subject, and the family and school provisionvariesby region (Liu et al., 2023). Meanwhile, South Korea launched the National Sex Education Guidelines in 2015 and revised the materials in 2017, but studies revealed that parental discomfort and absence of social consensus continue to hinder progress (Jeong et al., 2023; UNESCO, 2023). These findings indicate the necessity of diving more deeply into the parental role in sexuality education for children, especially in culture-sensitive contexts.

The acceptance of sex-related topics in some Asian societies continues at a poor level, with parents often hesitant and resistant to sexuality education owing to cultural, traditional, and social factors (Leung et al., 2019). Cultural taboos and societal expectations contribute to a general reluctance to discuss sexuality, especially in the family environment. For instance, surveys reveal Malaysian parents feel unprepared and lack the knowledgeto educate their children due to cultural sensitivity and the absence of community support (Balakrishnan & Singh, 2023; Binti Abdullah et al., 2020). Similarly, about 60% parents in South Korea had never delivered sexuality education and frequently reported a lack of competence, discomfort, and embarrassment in talking about sex with young children (Lee & Kweon, 2013; Shin et al., 2019). Such findings emphasize how deeply ingrained cultural norms affect parental involvement, resulting in missed opportunities to foster children’s healthy sexuality values. This disparity highlights the urgent need for evidence-based, culturally sensitive interventions to empower parents and break the cycle of silence surrounding sexuality education.

There is a significant contradiction between parents' perceptions and practicalbehavioursin sexuality education. While many expressed their willingness to deliver high-quality sexuality education to support their children’s sexual development (W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023; Shin et al., 2019), most lack in the personal resources and competencies required to implement effective education, reflected in the uncertainty about appropriate instructional content, methods, strategies, and limited skills of incident prevention – for example, less than half of the parents can identify the signs and symptoms of CSA and know when to intervene (Aun et al., 2022; Balakrishnan & Singh, 2023; Bennett & Harden, 2019;Nghipondoka-Lukolo& Charles, 2016; Noorman et al., 2023; Rudolph et al., 2023). Such difficulties stemmed primarily from a lack of knowledge of CSA-related indicators, includingbehaviouralchanges, emotional responses, and physical signs. This issue further highlights the urgent need for parents to receive professional training to strengthen their knowledge of sexuality education.

Nevertheless, sexuality education in Asia is facing several obstacles, including varying curriculum content and quality, shortage of well-trained educators, insufficient backup from schools and the community, and resistance from parental authorities (Liu et al., 2023; UNESCO & UNFPA, 2018; UNFPA & UNESCO, 2022). Some countries like China have not made it mandatory at any educational stage (Liu et al., 2023; UNFPA & UNESCO, 2022), leading parents, as key players in children's sexuality education, often rely on informal and unverified sources of knowledge due to a lack of professional training and guidance. Affected by cultural bias and one-sided information, parents' poor understanding of sexuality could mislead the formation of children's sexuality concepts.

Despite the critical role of sexuality education in shaping children’s development, identity, and self-protection, research on parental understanding and involvement remains scarce in Asia. The gap is particularly worrisome given the critical role of parents in shaping children's sexual values, especially in light of limited schooling. While some studies exist on the topic, there is a lack of a comprehensive synthesis of empirical evidence in the Asian context. Thus, the current study seeks toanalyseprevious studies on parental knowledge and sexuality education for children within the Asian context. A comprehensive picture of the current landscape could be presented by reviewing and synthesizing the published literature on sexuality education with the following research questions:

1. What is the status of Asian parents’ knowledge of sexuality education for children?

2. What factors influence Asian parents’ knowledge of sexuality education for children?

Methodology

Search Strategy

The purpose of this scoping review is to cast a broad and inclusive net to encompass every dimension of the development of early childhood sexuality education.Initially, the key concepts “sexuality education”, “early childhood”, “parents”, and “knowledge” were identified as anchors. These werethen enriched through seeking synonyms, related terms, and variations of the keywords, by referring to the online thesaurus,terminology from prior studies, and experts’ suggestions.Boolean operators (AND/OR) and truncation symbols (e.g., *) were employed to structure the search logic. A summary of the search strategy is provided in Table 1, and the full search strings are available in the supplement file.

There were two stages to the search process. To begin with, two databases, Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus, were accessed and completed the searching action on December 12, 2024. It was done by searching the databases with titles, keywords, and abstracts. The database-embedded filtering function was utilized when performing queries in the databases, by setting the following criteria for preliminary auto-filtering: (a) the publication date is 2014-2024, (b) it is an article, and (c) it is available in English and Chinese. An overview ofthe search string and database searches is presented in the table below (Table 1). It was generated 8194 articles from the digital databases, which contain 7727 articles and 467 articles from WOS and Scopus, respectively. Results of all studies were limited to English and Chinese, yielding 8164 articles in English and 30 articles in Chinese. The second phase lasted for about one week, began on December 25, 2024, and focused on manually scanning the reference lists of the articles to determine whether there were any additional eligible papers matching the criteria.

Table 1. Key Concepts & Overview of Database Searches

| Databases | Key Concepts Included | Number of Articles Retrieved | Data Accessed |

| Web of Science | Parents/families; knowledge/awareness; young children (e.g., pre-school, elementary); sexuality education | 7727 | 12/11/2024 |

| Scopus | Parents/families; knowledge/awareness; young children (e.g., preschool, elementary); sexuality education | 467 | 12/11/2024 |

Eligible Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study were structured to ensure the relevance and quality of the studiesanalysed. The review was limited to articles published between 2014 and 2024 to capture the latest trends and developments in the field of sexuality education. Only research written in English and Chinese were included as the authors intended to avoid translation challenges that may arise with articles in other languages. Focusing on empirical research, this study includes qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research, therefore secondary data such as systematic reviews were excluded. To maintain consistency and relevance, only article was included in the review, leaving out other types of documents such as books, book chapters, and conference papers. Since the main objective of this study was to explore the status of early childhood sexuality education in the Asian context, the reviews were geographically focused on Asia and studies conducted outside the region were excluded.

Although no formal interrater reliability statistics were calculated in this review, all retrieved articles were independently screened by two researchers using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were discussed and resolved through consensus to ensure accuracy and consistency in study selection. The decision not to calculate statistical agreement was based on the relatively small number of included studies and the use of a thorough discussion-based approach to reconcile differences.

Screening & Study Selection

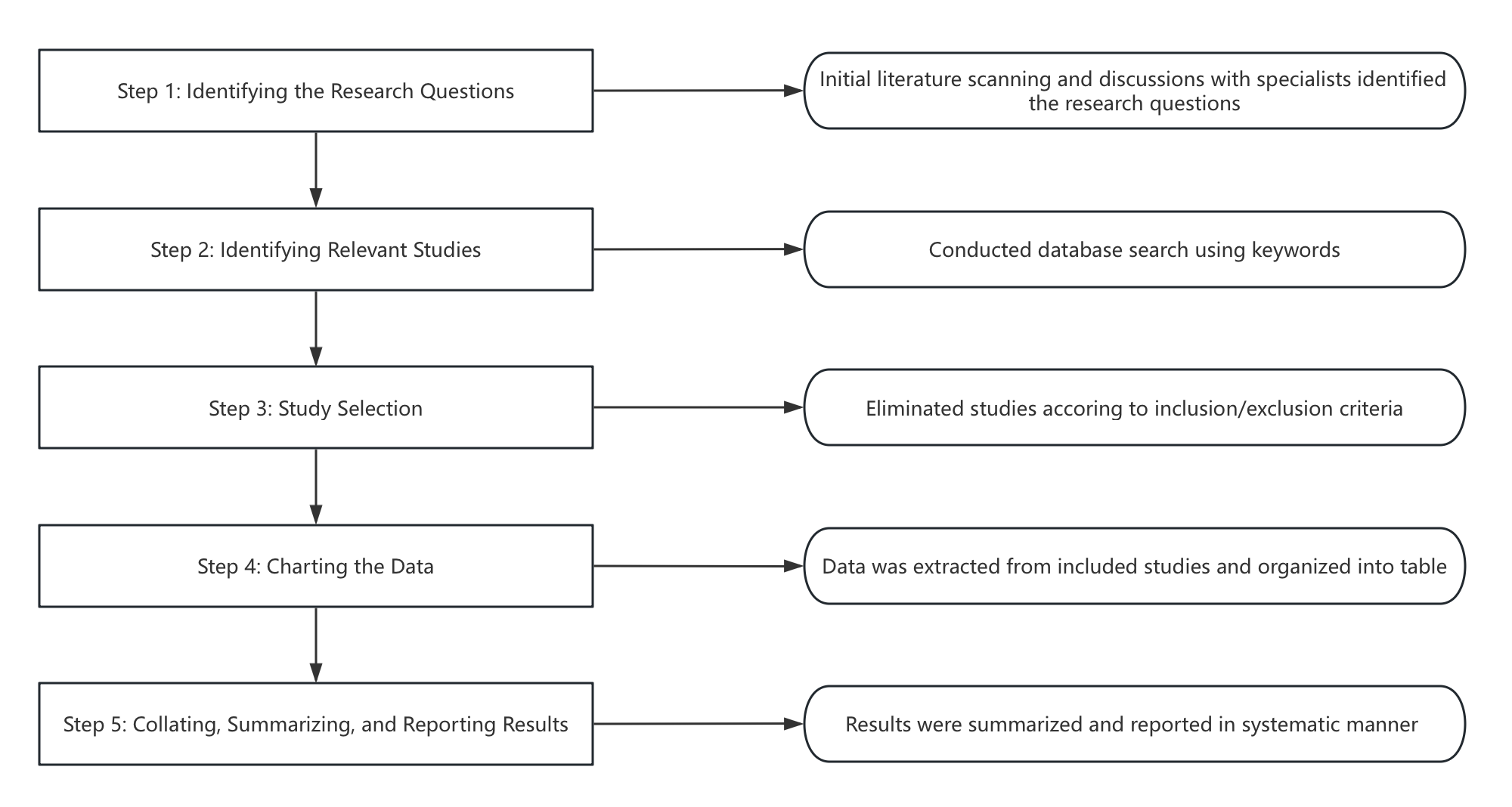

The detailed flow of study selection and screening was performed in accordance with the Arksey and O'Malley’s guidelines with five stages(Arksey & O’Malley, 2005)(Figure 1).

Figure 1. Steps of Arksey and O’Malley’s Scoping Review Strategy

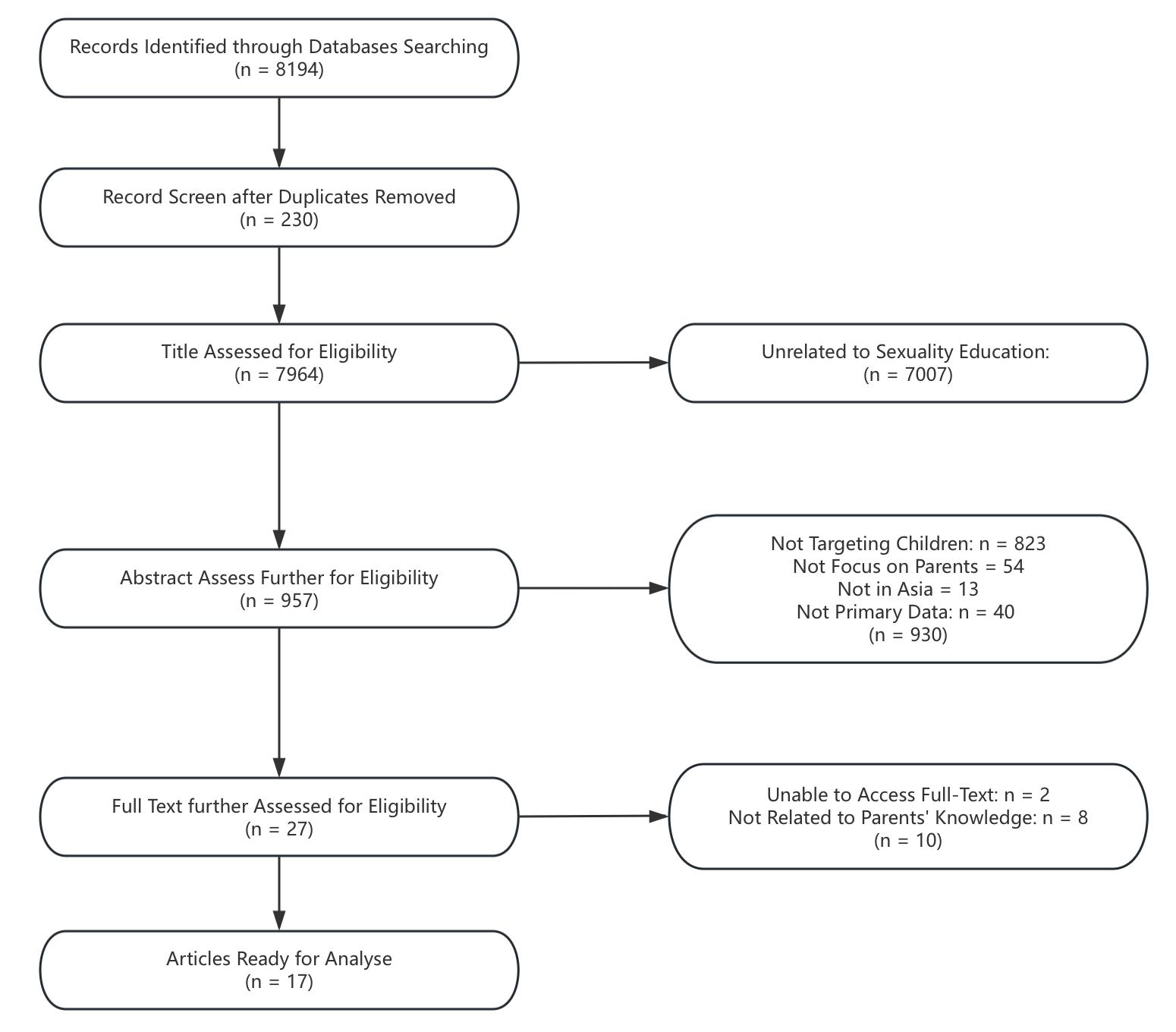

As shown in Figure 2, an initial search identified 8,194 relevant articles. The data were then organized in Excel for further analysis. All 230 duplicates were firstly removed. The researcher then proceeded with an elementary filtering and categorizing according to titles and abstracts, using the following strategy: (a) articles that fully met the inclusion criteria, (b) articles that required further review to confirm eligibility, and (c) articles that were eliminated as they were completely irrelevant to the study topic. Among those excluded were: (a) completely unrelated to sexuality education (7007 articles), (b) connected to sexuality education but targeting an educational level other than childhood stage (823 articles), (c) falling into the category of research on sexuality education in childhood stage yet the study population is not parents (54 articles), (d) focusing on the group of parents but not conducted in Asia countries (13 articles), and (e) using secondary data for the research design which did not meet the inclusion criteria (40 articles). With an action of further assessing the remaining articles, 2 papers are unable to access the full-text, and another 8 are not focusing on measure the knowledge of parents in terms of sexuality education for young children, and these 10 works were decided to be excluded. It is implying that a total of 8177 items were eliminated, resulting in a current remaining balance of 17 articles for the following review.

Figure 2. Study Flow Diagram

Results

Study Characteristics

The studies that form the foundation of this review have varied in size, analytical rigor, and generalizability of findings. The included studies consist of 11 quantitative studies, three qualitative descriptive studies, and three experimental studies that were studied in China, Iran, Jordan, India, and Indonesia. The papers were written in two languages, English (14 articles) and Chinese (3 articles). These studies together would produce strong evidence for reviewing Asian parents' knowledge about sexuality education. A description of the basic information of the 17 included studies is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of Study Characteristics

| Article | Location | Study Design | Sample Size | Mentioned Topics | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||

| Alzoubi et al. (2017) | Jordan | QN | 488 Jordanian Mothers Who Have Children Underage 12 | / | |||||||

| Xu and Cheung (2023) | China | QN | 508 Parents of Primary School Children | / | |||||||

| Hasibuan et al. (2021) | Indonesia | QN | 225 Parents of Children Aged 0–6 Years | / | / | / | |||||

| Prabhu et al. (2023) | India | QN | 90 Teachers and 50 Parents from Selected Primary Schools | / | |||||||

| Zhou et al. (2022) | China | QN | 1438 Parents and 1438 Children from 24 Kindergartens | / | / | / | / | ||||

| X. Zhang et al. (2020) | China | QN | 2246 Parents of Children from 20 Kindergartens | / | / | / | |||||

| W. Zhang et al. (2020) | China | QN | 373 Parents of Preschool-Aged Children from 16 Classes in 3 Preschools | / | |||||||

| Yan et al. (2023) | China | QN | 1015 Parents of Children Aged 3-6 from 16 Kindergartens | / | / | / | / | / | |||

| Leung Ling and Chen (2017) | China | QN | 2096 Parents of Students from 12 Schools (Including Kindergarten, Elementary School, And Secondary School) | / | / | / | / | / | |||

| Ganji et al. (2022) | Iran | QN | 600 Parents Who Have At Least One Child Underage 12 | / | |||||||

| W. Zhang and Yuan (2023) | China | QN | 19745 Parents of Primary School Children from 15 Schools | / | / | / | |||||

| Xie et al. (2016) | China | QL-Semi | 26 Parents of Preschool and Primary School Children | / | |||||||

| Ganji et al. (2018) | Iran | QL-Semi | 39 Parents of Children Underage 12 | / | / | / | |||||

| Merghati-Khoei et al. (2014) | Iran | QL-Semi | 26 Parents of Primary School Children Who Are Muslim | / | / | / | / | / | |||

| Jin et al. (2018) | China | QN-Exp | 904 Parents and 452 Children at Primary School Age | / | |||||||

| Martin et al. (2018) | Iran | QN-Exp | 80 Mothers of Preschool Children | / | / | / | / | ||||

| Mobredi et al. (2018) | Iran | QN-Exp | 78 Mothers of Preschoolers Aged 3-6 | / | / | / | / |

Note.Topics 1–8 refer to the following: 1 = Relationships; 2 = Values, Rights, Culture and Sexuality; 3 = Understanding Gender; 4 = Violence and Staying Safety; 5 = Skills for Health and Well-Being; 6 = The Human Body and Development; 7 = Sex and SexualBehaviour; 8 = Sexual and Reproductive Health. A slash( /) indicates that the topic was mentioned in the study.

Study design abbreviations: QN = Quantitative Study; QL-Semi = Qualitative Semi-structured Interviews; QN-Exp = Quantitative Experimental Study

Participant Characteristics

A total of 31,917 participants took part in the included studies: 93.80% (29,937) were parents, 0.28% (90) were teachers, and 5.92% (1890) were young children. As the objective of this review is to gain an understanding of parents' knowledge of sexuality education for children, the following analysis focuses only on the research results from parents.

The majority of the 29,937 participants of the children's parents who were involved in the inclusion studies were female, with 6985 (23.33%) males and 22,952 (76.67%) females, respectively, with three of the studies only involving female participants (Martin et al., 2018;Mobrediet al., 2018; Alzoubi et al., 2017).

Out of the seventeen studies, most were targeted at parents of children in kindergarten and primary school, with six (Martin et al., 2018;Mobrediet al., 2018; Yan et al., 2023; W. Zhang et al., 2020; X. Zhang et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2022) and five (Jin et al., 2018;Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014; Xie et al., 2016; Xu & Cheung, 2023; W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023) studies addressing parents of kindergarten children and parents of primary school-aged children, respectively; one paper covered parents of children in both kindergarten and elementary school (Xie et al., 2016); one study focused on parents of children aged 0-6 (Hasibuanet al., 2021); three research specified parents of children aged 0-12 years as the target population (Alzoubi et al., 2017; Ganji et al., 2022, 2018), and another study encompassed parents of children in kindergarten, elementary school, and secondary school with no further clarification (Leung Ling & Chen, 2017).

Parental Knowledge of Sexuality Education

Despite a few studies pointing to a high level of general knowledge about sexuality education among parents of children (Hasibuanet al., 2021), more studies conclude that Asian parents generally have a weak understanding of the basics and methodologies of sexuality education (Ganji et al., 2022, 2018; Martin et al., 2018;Mobrediet al., 2018; Yan et al., 2023). For instance, in a study of 600 parents in Iran, only 66.7% of parents achieved an intermediate level of knowledge related to children's sexualbehaviour, whereas 5% could respond appropriately to related situations (Ganji et al., 2022).

Although some parents expressed willingness to discuss sex-related topics with children, their efforts are hindered by weak content knowledge and limited pedagogical competence. Studies have noted that less than 40% of parents can correctly use professional terminology related to sexuality education, reflecting a superficial grasp of sexuality education (W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023). Under these circumstances, many had to choose alternative ways, such as through television and the Internet (70%) and by reading books (63%), though the effectiveness of these approaches is clearly limited by parental competence (W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023).

Studies also pointed out that only a minority of parents can comprehensively cover the full range of topics involved in sexuality education (W. Zhang et al., 2020; W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023). Findings from a study of 19,745 Chinese parents reveal that though over 80% of parents self-assessed familiarity with correct genital terminology and daily sexual health care, almost half were unaware of sexual development andbehaviourthroughout childhood and nearly three-fifths had no knowledge of the sexual issues that their children might encounter like CSA (W. Zhang et al., 2020). Some parents hold biased views, believing that only certain subjects—such as basic anatomy or reproductive health—are appropriate for young children, while topics like gender diversity and sexual minorities should be excluded (Leung Ling & Chen, 2017).

Parental understanding ofCSA alsoremains insufficient. For instance, one participant in China stated, “I don't hear of many… (cases of CSA). … Most people would not have experienced this.”(Xie et al., 2016). Although almost all parents had warned children about strangers (W. Zhang et al., 2020), many failed to recognize non-contact forms of abuse. 92% parents in a study only defined CSA as a form of physical contact whileoverlookingnon-contact abuseissues such as young children being exposed to pornographic content(Xie et al., 2016).Additionally,77% of the participants believed thatgirls were more vulnerable to abuse than boys, with some denying that boys could be victims or suffer psychological harm(Xie et al., (2016).

Furthermore, a survey indicated that many mothers possessed some understanding of the basic definition of CSA and certain preventive measures but were grossly unaware of knowledge regarding the relevant laws and child protection services. A study indicated that only 37.7% were familiar with CSA-related laws and less than 50% were aware of child protection services (Alzoubi et al., 2017).

Challenges in Parental Communication on Sexuality

When confronted with children's sexual curiosity and questions, parents are often incapable of responding effectively, or even opt for avoidance, owing to insufficient knowledge and communication skills (Ganji et al., 2018;Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014;Mobrediet al., 2018; W. Zhang et al., 2020; X. Zhang et al., 2020). Common responses such as silence and evasion are often rooted in parents’ misconceptions that children are not sexually aware, and sexuality topic is inappropriate for a child’s age, along with lack of biological understanding, shortage of communication skills, and feelings of shame and embarrassment (e.g. the use of chests in place of breasts) (Ganji et al., 2022;Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014;Mobrediet al., 2018; Yan et al., 2023).

These reactions may be rooted in the misconception that young children are sexually unaware or that discussing sexuality is age inappropriate. Some parents expressed misunderstanding of the nature of sexuality education, thinking that children are sexually ignorant and viewing children's sexualbehaviouras dangerous or immoral, prompting overly restrictive parenting approaches (Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014). Such a point contributes to parental unease and a reluctance to engage in proactive sexuality education.

Gender disparities in parental communication were noted. Mothers were more likely than fathers to engage in discussions with their children on related topics (Jin et al., 2018;Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014; Xu & Cheung, 2023), and few parents could treat their children of different genders equally (Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014), reflecting ingrained bias.

Despite many parents strongly emphasized the significance of supervising children in papers, they showed contradictions and inconsistencies in their performance. While many stressed the importance of supervision,few reported the ability to manage or guide children’s sexuality effectively, as stated by several participants, “we were unable to control/regulate their children's sexuality” (Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014). Additionally, many also voiced concerns about the use of digital media. They reported feeling the influence of parent-child connection, increasing attention to sexual issues, and feeling powerless about how to monitor the use of media to protect children from objectionable information (Ganji et al., 2018;Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014; Xie et al., 2016).

Factors Influencing Parents’ Knowledge

Parents' level of knowledge and perceptions of their children's sexuality education are shaped by a variety of factors. This paper categorizes these factors into three main categories: cultural factors, demographic factors and socio-economic factors.

Cultural Factors

Cultural factors significantly influence parents' knowledge acquisition and acceptability of sexuality education.In more open societieslike Hong Kong,China, parents are relatively more liberal and willing to discuss topics related to sexuality, which is also reflected in their knowledge of sexuality education (Leung Ling & Chen, 2017). However,in more conservative societieslike Iran, India, and the Chinese mainland, sexuality educationremains a taboo subject(Ganji et al., 2018; Prabhu et al., 2023; Xie et al., 2016).

Fears that discussing sexualitywith young childrenmight encouragechildren to adopt ''free lifestyles'' like free sex (Hasibuanet al., 2021), and prejudices about sexuality education (Hasibuanet al., 2021;Merghati-Khoeiet al., 2014; X. Zhang et al., 2020),contributed to parental hesitation.In a qualitative study conducted in China, for instance, participants mentioned that “Chinese society is still relatively conservative .... I don't know how to start the conversation with my child about sex....”, other participants also made a similar statement that “maybe there are more constraints for women in Chinese society” (Xie et al., 2016). Similarly,Merghati-Khoeiet al., (2014) pointed out that while parents have recognized generational and cultural shifts, they have difficulty applying the changes to their own young children's sexuality education.

Additionally, religionalso played a notable role.In a study conducted in Hong Kong, religious beliefs were found to influence parents’ perspectives on topics such as love, contraception, and homosexuality(Leung Ling & Chen, 2017). Similarly,Merghati-Khoeiet al. (2014) conducted a qualitative study in Iran identified religion as a significant factor influencing parents' understanding of sexuality, making them view sexuality as an innate phenomenon and believed sexuality education was totally unnecessary for children. As oneparticipantstated, “overeducating children are reasons for promiscuity in Western societies”.

Demographic Factors

While some studies have concluded that there is no significant association between demographic characteristics and parental knowledge of sexuality education (Ganji et al., 2022; Martin et al., 2018), many other studies suggest that parental education level, gender, age, family status, and sexuality education experiences are significantly associated with their knowledge of sexuality education.

It has been demonstrated that parents with higher levels of education have a deeper knowledge of sexuality education and sexual abuse prevention, not only understanding the implications of relevant theories and practices, but also being able to recognize and respond to possible risky situations (Ganji et al., 2022; Jin et al., 2018; Prabhu et al., 2023; Yan et al., 2023; Zhang & Yuan, 2023; Zhou et al., 2022). A higher level of education also makes them more inclined to adopt active and effective educational practices and to update their knowledge based on scientific developments (Leung Ling & Chen, 2017).

Age differences were also evident.Parents of different age groups showed remarkable differences in group characteristics in terms of their understandings and reactions when it comes to sensitive topics like love, contraception, and homosexuality (Leung Ling & Chen, 2017). Parents of younger age groups generally had a certain advantage in terms of knowledge and were better able to put the concepts of sexuality education into practice with a better rate of consistency in the “knowledge-belief-activity” (Yan et al., 2023).

Results also revealed that gender acts as aninfluencingfactor. Studies done in China have mentioned that despite long-standing cultural influences due to Chinese society's demand for passivity and restraint haveshaped women's self-perceptions of disliking sex, avoiding sex, and even hating sex (Xie et al., 2016), mothers' level of knowledge and ability to learn actively have been measured as higher than that of fathers in some studies (Yan et al., 2023; W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023; W. Zhang et al., 2020). Other researchers have emphasized that there was no significant difference between the father's knowledge level and the mother's knowledge level in terms of sexuality education for children within the same family (Jin et al., 2018).

Additional factors cited in these 17 articles that might impact the level of parental knowledge of sexuality education are: there is no relationship between the number of children in the family and parental knowledge of sexuality education (Ganji et al., 2022), there is a significant relationship between parental knowledge of sexuality education and marital status (Prabhu et al., 2023), and parents who had received sexuality education at home or at school during childhood showed higher knowledge scores in comparison to those who had not received sexuality education (W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023; W. Zhang et al., 2020).

Socio-Economic Factors

Socio-economic background also influences parents' knowledge of sexuality education and their ability to practice it. There are large differences in parents' knowledge and the effectiveness of sexuality education implementation between urban and rural areas and among various social classes. Parents in rural areas had a shortage of sex-related knowledge and low rates of congruence between knowledge, attitudes, and practice due to their low educational attainment, scarce sexuality education resources, and cultural biases in children's education, which indirectly influence children's sexuality education practices (X. Zhang et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2023). It was found that urban parents' knowledge was superior to those of rural parents (Zhou et al., 2022).

Findings on the association between parents' economic status and their knowledge of children's sexuality education vary considerably. Some showed that parents with a higher income reported a higher rate of good sexuality education knowledge and beliefs (W. Zhang & Yuan, 2023; Zhou et al., 2022). Yet some studies disagreed and stated that there was no significant correlation between the level of parental knowledge and their economic condition (Ganji et al., 2022). Moreover, some parents strongly believed the risk and likelihood of their children experiencing CSA was related to the family's socio-economic status, especially the poverty level (Xie et al., 2016).

Effectiveness of Interventions

Studies show that targeted sexuality education interventions, particularly for mothers, can significantly improve parental knowledge. One randomized controlled study in Iran aimed to evaluate the effect of a newly developed sexuality education program on the knowledge and attitudes of 80 preschoolers' mothers (Martin et al., 2018). No significant difference was found between the control and experimental groups before the intervention, but post-intervention scores were significantly higher in the experimental group across all six themes, especially regarding knowledge of the stages of sexual development and the correct method of sex education.

In line with this, another study carried out also in Iran assessed the sexuality education knowledge of 78 mothers which further supported the effectiveness of the sexuality education program (Mobrediet al., 2018). The study revealed that mothers' knowledge related to sexuality education had significantly improved following the sexuality education intervention.

Conclusion

Parental Knowledge of Sexuality Education

Results of this study identified that despite some parents possessing some basic knowledge about sexuality education, overall, many parents have a seriously inadequate knowledge base in childhood sexuality education and a lack of skills in determining the appropriate time and manner of education. Cultural taboos, stigma, and misconceptions regarding childhood sexual development have generally inhibited the open communication of sexual topics in families. The findings suggest that parental inadequacy in early childhood sexuality education is not solely an individual issue but is shaped by deep-rooted cultural norms and traditional values, which substantially hinder the effective implementation of sexuality education for children.

The findings also indicate that although many Asian parents recognized the significance of sexuality education and believed it should originate within the family, their efforts are hindered by a lack of skills and knowledge to implement sexuality education in practice and a pervasive sense of powerlessness. Social norms, absence of formal educational background,and uncertainty about appropriate instructional strategies cause parents internalized anxiety and insecurity about children's sexuality education, leading to silence and ignorance of the topic altogether. While parents want to be protective, such “silent education” produces risks of children's acquiring false or one-sided perceptions of sexuality through informal channels (e.g., peers, the Internet, etc.) and weakens their self-protection abilities, resulting in increased misunderstandings, riskybehaviours, and vulnerability to victimization(Othman et al., 2020).

Many parents identify CSA only with physical contact, overlooking non-contact forms of risk, such as exposure to explicit materials, sexually suggestive language, or voyeuristicbehaviours. This narrow understanding reflects parents' inadequate knowledge of childhood sexual developmental milestones, psychological responses, and social risks in a holistic manner, neglecting the potential risks and their possible far-reaching effects on young children's sexual concepts, emotions, andbehaviours. Such misconceptions may lead to parental delays in intervening or even the continuation of danger due to the failure to recognize early warning signs when faced with real risks, with potential lasting damage to the child's sexuality and interpersonal safety.

Moreover, the stereotypes that only girls are being victimized or that only strangers commit sexual abuse hide the reality of CSA, causing missed opportunities for prevention. Such perceptions not only leave parents vulnerable to ignoring cases of CSA by acquaintances or family members but also cause difficulties for boys who suffer from CSA to be detected, speak out, and access support and intervention. Such deep-rooted prejudices and misconceptions undermine parents' ability to recognize risk and to effectively protect their children.

The inconsistent implementation of CSA prevention policies and the inconsistency in legal awareness across Asia further exacerbate the problem. For instance, in India, the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO) 2012 mandates the reporting of CSA and the inclusion of CSA prevention and awareness programs for adults (The Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act,2023). Meanwhile, Singapore’s Children and Young Persons Act, revised in 2020,requires parents and educators to take an active role in CSA prevention (Children and Young Persons Act 1993, 2020). However, despite efforts made on the national legislations, parents' awareness of the relevant laws, regulations,and service resources is still low, constraining their ability to intervene in a timely manner and effectively respond to the incidents.The findings indicate the urgent need to enhance parents’ understanding of CSA, including gender-neutral perspectives, non-traditional forms of abuse, and legal protection.It suggests policymakers and the social welfare authorities should publicize the laws, regulations,and service resources through multiple channels to raise parents' knowledge and awareness and facilitate their timely recognition and effective intervention in such matters.

Challenges in Parental Communication on Sexuality

Parents' silence or avoidance in sexuality-related conversations often stems from their own deep-seated misunderstandings about young children's sexual development. Mistakenly perceiving children as sexually unaware or assuming such discussions will stimulate unwantedbehaviours, parents avoid communication with their children or use subtle alternative language instead. This response limits the child's opportunities to receive accurate, age-appropriate information and reinforces the inappropriate notion of sexuality as taboo. It highlights the pressing need to address parental misconceptions about childhood sexuality and to encourage open, age-appropriate dialogue that can empower children and reduce stigmatization.

Gender disparities in home-based sexuality education were also uncovered. The mothers were more proactive in educating the children,whereas the fathers were less involved. Yet, the findings point out that mothers often tend to focus on the negative dimensions of sexualbehaviourand overlook the significance of healthy, positive sexual experiences throughout childhood. The imbalance may embed fear, shame,or confusion in children's minds, restricting their power to form healthy sexual gender identities. The limited participation of fathers not only reinforces gender-biased child-rearing norms but also denies access to gender balanced perspectives and role models for children. It is consistent with the analysis of patriarchal cultural influences and the limitations of traditional beliefs about the scope of sexuality education in existing research(Pell, 2023), which constrain open dialogues. Tackling the issues calls for culturally sensitive strategies that actively engage both parents,facilitate gender-equitable communication, and widen knowledge of sexuality to advance the next generation's full understanding and knowledge of sexuality.

The research also revealed the ambivalence expressed by parents when dealing with the media. While relying on the media to provide sexuality education to children as a compensatory mechanism for their own loss of knowledge and skills, the other side voiced mistrust because of concerns about asymmetric information and misaligned values. Such contradiction not only mirrors parents' confusion and anxiety in positioning their roles in sexuality education due to poor knowledge,but it also further exacerbates the weakening of parents' discourse in sexuality education because of their contradictorybehaviours,which may put children in a dilemma of conflicting information and varying norms in facing sexuality knowledge. Ithighlights the tension between family education and media usage, emphasizing the importance of equipping parents with accurate knowledge and effective communication strategies to critically evaluate media content and serve as reliable guides throughout their children's sexualdevelopment process.

Factors Influencing Parents’ Knowledge

The study uncovers notable contextual, cultural, and socio-economic differences in parents' knowledge of sexuality education, further confirming the role of multiple social factors in shaping parents' knowledge of childhood sexuality education. It not only broadens understanding of child sexuality education practices in families but also proposes new thinking paths forcountries'localized adaptation of global sexuality education guidance.

Firstly, findings indicate that parents tend to be more open to accepting sexuality education and display higher knowledge levels within a more open social setting. It reflects a close correlation between the acceptability of sexuality education and the social and cultural atmosphere. In conservative cultural contexts, however, sexuality remains a sensitive or taboo issue, where parents are inclined to internalize cultural expectations that block open dialogue. The norms feed the sense of reticence and shame, leading parents to regard discussing sexuality with their children as morally inappropriate or harmful. Consequently, it is possible for them to perceive sexuality education as a risk to traditional values rather than as a tool to protect and nurture children's growth. Additionally, religion may further exacerbate such situations, as some religious beliefs perceive sexuality as instinctive rather than educational, rendering systematic instruction unnecessary and even dangerous. Such cultural constraints lead to the loss of parents' ability and willingness to acquire correct sexuality knowledge and increase the communication gap between generations on sexuality topics. These cultural influences further illuminate the cultural friction and value conflicts that may confront the promotion of children's sexuality education in the Asian context,signallingthe imperative of interrogating and emphasizing the cultural sensitivity of childhood sexuality education.

Furthermore, consistent with the reciprocal determinism from Bandura, parents' knowledge building regarding children's sexuality education is closely related to their socio-economic background and early experiences(Bandura, 1977). Research suggests that parents with higher levels of education have a better understanding of concepts related to sexuality education, a greater ability to recognize and cope with related risks, and morefavourableattitudes toward accepting science-based knowledge on sexuality. Hence, improving the overall educational level could be a key entry point to enhance the effectiveness of family sexuality education for children, especially in Asian societies where sexuality is still culturally taboo.

Age differences reflect the reconfiguration of knowledge gain paths at varying ages. Younger parents were more receptive to open concepts of sexuality and better at acquiring educational resources through diversified channels, exhibiting stronger consistency between knowledge, attitudes,andbehaviours. The findings emphasize the imperative of differentiated educational responses that are sensitive to the learning preferences and challenges experienced by parents of different ages, which implies that future sexuality education policies should pay more attention to the spread of messages between generations.

Meanwhile, gender remains a key issue. Despite most evidence of mothers' dominance in sexuality education practices, fathers' absence might pose an implicit risk to the gender identity development of children.A gender imbalance in sexuality education not only reduces the integrity of family educationbut may also bias children's gender identities, relationship perceptions, and social expectations(UNESCOet al., 2018). Hence, this phenomenon of gender disparity in home-based sexuality education reminds us to focus onfathers'engagementand the exploration of effective intervention mechanisms to achieve gender-balanced education patterns in both policy and practice.

Besides, results support the significant influence of socio-economic backgroundonparents' knowledge and practicing ability in sexuality education. It disclosed a considerable inequality between parents in urban and rural areas regarding their knowledge of childhood sexuality education. Suchaphenomenon reveals not only the imbalance in the allocation of educational resources but also the systematic shortcomings in socio-cultural, information access, and sexuality education programs in rural areas. Lack of resources makes rural parents more prone to knowledge gaps and coping dilemmas in sexual education matters that constrain their ability to protect their children from sexual abuse and other risks. Therefore, it is recommended to take further consideration of the educational resource distribution and geographic differences when promoting sexuality education in families to enhance rural parents' knowledge of sexuality education for children.

Additionally, the conclusions from studies in different areas were inconsistent on the effect of the family economic status on parents' knowledge of sexuality education. It suggests that while economic factor is regarded as one of the important research factors in sexuality education, the relationship between them and parents' sexuality knowledge may be moderated and influenced by other social factors, which is suggested to be further studied to provide more targeted evidence for policy decisions.

Intervention Programs

Findings revealed that a systematic educational intervention targeting mothers of preschoolers significantly increased their knowledge of multiple aspects of sexuality education. The finding supports the idea ofSocial Learning Theory regarding the importance of parenting roles in family education(Bandura, 1977). Upgrading mothers' knowledge of sexuality education helps overcome thefamily'ssilence on sexuality education. It may contribute to the creation of a more open, scientific, and respectful parent-child sexual communication environment, thereby laying the foundation for children's healthy sexual concepts and gender awareness later.

This finding provides important lessons for the Asian context,where sexuality education is in its formative stages of implementation. Particularly when parents are the subject of childhood education, their increased knowledge triggers changes in attitudes andbehaviouralpractices that can contribute to children's long-term well-being development. The affirmation of the feasibility and effectiveness of the interventions adds value to both policy development and educational practice. It provides evidence-based strategies to assist in building a synergistic and cooperative support system for children's sexuality education among families, schools,and society, therefore strengthening the social safeguard of children's sexual rights and sexual health.

It is worth mentioning, however, that the intervention programs included in this study focused on mothers and lacked a systematic exploration of fathers' interventions and roles. The blind spot echoes the aforementioned missing role of fathers in family sexuality education, hinting at the problem of gender imbalance in intervention practices. Thus, future research should place greater emphasis on the role of fathers in children's sexuality education and their influence on it, and examine whether appropriate intervention strategies could effectively enhance their willingness to educate, their knowledge,and their ability to practice, thus balancing gender engagement in family sexuality education.

In summary, the study has revealed the profound influence of social factors on the quality of family sexuality education, highlighting the need to address the differentiated needs of diverse communities and facilitating the building of accessible, inclusive, and equitable family sexuality education support systems. The findings highlight significant knowledge gaps and discomfort among parents regarding sexuality education, with many struggling to balance cultural norms and the need for age-appropriate education. Addressing these challenges requires culturally sensitive and accessible intervention strategies that empower parents' capacity to enhance parents’ knowledge, reduce stigma, and foster open family dialogue. Specifically, there are opportunities for public activities to normalize sexuality discussions and raise awareness of family sexuality education, along with the establishment of targeted, evidence-based trainingprogrammesfor parents to strengthen their knowledge and skills regarding child sexuality education. The incorporation of home-based sexuality education into broader child protection frameworks and public policies is also vital to further strengthen systemic support. The findings offer both practical insights for preventing CSA and political value to improving family engagement in sexuality education within comprehensive child welfare systems.

Limitations

Language Bias:This review only included studies published in English and Chinese, leading to potential language and publication bias. Relevant research published in Korean, Thai, Japanese, or other regional languages may contain culturally specific insights that are absent here. For instance, Thailand has various national curriculum development plans (UNICEF, 2016), and Korea has an active government-ledapproach (UNESCO, 2023), which may have influenced findings differently if included. Consequently, this review is more reflective of English- and Chinese-speaking academic perspectives, potentially overlooking broader regional diversity.

Database and Source Limitation:This review relied exclusively on journal articles from two academic databases, excluding grey literature such as conference papers, policy reports, and non-governmental organization publications. These resources often provide practical, real-world insights into how sexuality education is implemented at the community level. As a result, our findings may over-represent academic perspectives whileunder-representingreal-world implementation challenges, such as parental resistance, training barriers, and policy enforcement issues.

Self-Report Bias:Most studies in this review relied on parental self-reported data, which are subject to social desirability and recall biases. Parents may overreport their knowledge due to cultural sensitivity or lack of confidence, limiting data reliability. Future studies should integrate diverse sources such as observational methods, interviews with children, or educator perspectives to triangulate findings.

Methodological and ComparativeLimitations:The reviewed studies were cross-sectional, lacking longitudinal data that could track changes in parental attitudes over time. Additionally, this study does not compare findings with Western or African contexts, which could have provided useful cross-cultural insights. Future research should incorporate longitudinal and comparative studies to better understand how parental sexuality education knowledge evolves over time and across regions.

Recommendations

This review aimed to determine parents' knowledge of sexuality education for children and what factors influence their understanding, with the purpose of providing evidence on the role of parents in advancing young children’s sexuality education. While global awareness of early childhood sexuality education is growing, the primary research literature in the Asian context is limited. Most existing studies on sexuality education in Asian settings focused on adolescents, with only a few reporting on parental knowledge of sexuality education regarding early childhood. Between 2014-2024, only 17 studies met the criteria for inclusion in this review.

Findings indicate that Asian parents generally possess an insufficient and topic-specific understanding of childhood sexuality education, with varying degrees of engagement.Therefore, raising parental awareness is important to further promote its effective implementation it. Policymakers and educators should place emphasis on enhancing parents' comprehensive understanding of sexuality education topics for young children, including relationships, sexual values, and child safety and protection (e.g., CSA). It is suggested that future intervention programs consider fathers as the primary participants rather than just mothers to give a better picture of both parents' roles in sexuality education.Recommendations are also issued to strengthen the collaboration among schools, communities and government organizations to further develop culturally sensitive sexuality educationprogrammesand introduce consistent information for parents. For instance, they may jointly organize a series of workshops themed on childhood sexuality education, set up channels for counselling and guidance, and prepare customized educational resources tailored to the local cultural background, to assist parents in overcoming cultural barriers and feelings of embarrassment.

Further study should explore effective methods of sharing accurate sexuality education knowledge through various mediums to help parents effectively access scientific materials. For example, future studies are encouraged to incorporate and evaluate diversified delivery modes for sexuality education content to parents, such as social media campaigns, structured seminars, and supportive online modules, especially in rural or underserved areas. Demographic influences such as gender, age, education level, socio-economic status, and geographic location have shown inconsistent associations with parental knowledge, underscoring the need for additional studies to inform targeted support.

Future research should conduct cross-country comparisons and longitudinal studies to track changes in parental beliefs and understanding of sexuality education for young children, which would help identify the roles of various factors and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions. To support a more holistic synthesis of literature, future systematic reviews are encouraged to expand search strategies by incorporating wider academic databases, including grey literature, and adding publications beyond English and Chinese languages.

I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my supervisors, Dr. Kamariah Abu Bakar and Dr. NurulKhairaniIsmail, for they are priceless guidance, patience, and encouragement during my research.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Generative AI Statement

As the authors of this work, we used the AI tool ChatGPT to enhance the clarify, structure, and the linguistic accuracy of the manuscript to meet the academic standards. After using this AI tool, we thoroughly reviewed and verified the final version of our work. We, as the authors, take full responsibility for the content of our published work.

Authorship Contribution Statement

YumoDing conducted the scoping review,analysedthe data, and wrote the original draft. Dr. Kamariah Abu Bakar and Dr. NurulKhairaniIsmail supervised the research process and contributed to the critical review and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Reference

Alzoubi, F. A., Ali, R. A., Flah, I. H., &Alnatour, A. (2017). Mothers’ knowledge & perception about child sexual abuse in Jordan.Child Abuse and Neglect,75, 149-158.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.006

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework.International Journal of Social Research Methodology,8(1), 19-32.https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Aun, T. S., Mun, A. S., Mei, K. S., Jie, O. M., & Yee, K. J. (2022). Awareness and recognition on signs and symptoms of child sexual abuse (CSA) among Malaysian parents of Malay, Chinese and Indian descent.Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies,17(4), 289-299.https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2021.2001613

Balakrishnan, K., & Singh, G. K. S. (2023). Parents’ perspective on sex education implementation within the context of early childhood education in Malaysia.International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Science,13(8), 1404-1415.http://bit.ly/4ossQIL

Bandura, A. (1977).Social learning theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bennett, C., & Harden, J. (2019). Sexuality as taboo: Using interpretative phenomenological analysis and a Foucauldian lens to explore fathers’ practices in talking to their children about puberty, relationships and reproduction.Journal of Research in Nursing,24(1-2), 22-33.https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987118818863

Binti Abdullah, N. A. F., Muda, S. M., Zain, N. M., & Hamid, S. H. A. (2020). The role of parents in providing sexuality education to their children.Makara Journal of Health Research,24(3), 157-163.https://doi.org/10.7454/msk.v24i3.1235

Breuner, C. C., & Mattson, G. (2016). Sexuality education for children and adolescents.Pediatrics,138(2), Article e20161348.https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1348

Chan, A. E., Adler-Baeder, F. M., Duke, A. M., Ketring, S. A., & Smith, T. A. (2016). The role of parent-child interaction in community-based youth relationship education.The American Journal of Family Therapy,44(1), 36-45.https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2016.1145079

Chavula, M. P., Zulu, J. M., & Hurtig, A.-K. (2022). Factors influencing the integration of comprehensive sexuality education into educational systems in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review.Reproductive Health,19, Article 196.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01504-9

Children and Young Persons Act, 1993. (2020).https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/CYPA1993

Council of Europe. (2020).Comprehensive sexuality education protects children and helps build a safer, inclusive society. Gender Equality.https://bit.ly/4lHfDtv

Ganji, J., Emamian, M. H.,Maasoumi, R., Keramat, A., &Khoei, E. M. (2018). Qualitative needs assessment: Iranian parents’ perspectives in sexuality education of their children.Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Sciences,5(4), 140-146.https://brieflands.com/articles/jnms-141160.pdf

Ganji, J.,Merghati-Khoei, E.,Maasoumi, R., Keramat, A., & Emamian, M. (2022). Knowledge and attitude and practice of parents in response to their children’s sexualbehavior.Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Sciences,9(1), 45-51.https://brieflands.com/articles/jnms-140684.pdf

Federal Centre for Health Education. (2010).WHO regional office for Europe andBZgAstandards for sexuality education in Europe: A framework for policy makers, educational and health authorities and specialists.https://bit.ly/3GzcLA7

Haberland, N., & Rogow, D. (2015). Sexuality education: Emerging trends in evidence and practice.Journal of Adolescent Health,56(1), S15-S21.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.08.013

Hasibuan, R., Meilanie, S. M., Fitri, R., & Tampubolon, G. N. (2021). Parents knowledge of sex education on early childhood the feasibility for parenting.The International Journal of Early Childhood Learning,28(1), 29-38.https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-7939/CGP/v28i01/29-38

Jeong, E., Kim, J., & Koh, C. K. (2023). School health teachers’ gender-sensitive sexual health education experiences in South Korea.Sex Education,25(1), 81-94.https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2023.2272127

Jin, Y., Chen, J., & Yu, B. (2018). Parental practice of child sexual abuse prevention education in China: Does it have an influence on child’s outcome?Children and Youth Services Review,96, 64-69.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.11.029

Ketting, E., & Ivanova, O. (2018a).Sexuality education in Europe and Central Asia: State of the art and recent developments.BundeszentralefürgesundheitlicheAufklärung,BZgA.https://bit.ly/4lEpWyi

Ketting, E., & Ivanova, O. (2018b).Sexuality education in the WHO European region—Sweden.BundeszentralefürgesundheitlicheAufklärung,BZgA.https://bit.ly/3IdCCxU

Lee, E. M., & Kweon, Y.-R. (2013). Effects of a maternal sexuality education program for mothers of preschoolers.Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing,43(3), 370-378.https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2013.43.3.370

Leung, H., Shek, D. T. L., Leung, E., & Shek, E. Y. W. (2019). Development of contextually-relevant sexuality education: Lessons from a comprehensive review of adolescent sexuality education across cultures.International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health,16(4), Article 621.https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040621

Leung Ling, M. T. W., & Chen, H. F. (2017). Hong Kong’s parents’ views on sex, marriage, and homosexuality.Journal of Child and Family Studies,26, 1573-1582.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0672-1

Liu, W., Li, J., Li, H., & Zheng, H. (2023). Adaptation of global standards of comprehensive sexuality education in China: Characteristics, discussions, and expectations.Children,10(2), Article 409.https://doi.org/10.3390/children10020409

Martin, J., Riazi, H., Firoozi, A., & Nasiri, M. (2018). A sex education programme for mothers in Iran: Does preschool children’s sex education influence mothers’ knowledge and attitudes?Sex Education,18(2), 219-230.https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1428547

Merghati-Khoei, E.,Abolghasemi, N., & Smith, T. G. (2014). “Children are sexually innocent”: Iranian parents’ understanding of children’s sexuality.Archives of SexualBehavior,43, 587-595.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-013-0218-6

Mertoğlu, H. (2019). Science student teachers’ views and conceptions of the interdisciplinary sexual health education.Journal of Turkish Science Education,16(3), 379-393.http://bit.ly/4n3H4yg

Mobredi, K.,Hasanpoor–Azghady, S. B., Azin, S. A., Haghani, H., & Farahani, L. A. (2018). Effect of the sexual education program on the knowledge and attitude of preschoolers’ mothers.Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research,12(6), JC06-JC09.https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2018/32702.11616

Mokhtar, M. M., Rosenthal, D. A., Hocking, J. S., & Satar, N. A. (2013). Bridging the gap: Malaysian youths and the pedagogy of school-based sexual health education.Procedia - Social andBehavioralSciences,85, 236-245.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.355

Nghipondoka-Lukolo, L. N., & Charles, K. L. (2016). Parents’ participation in the sexuality education of their children in Namibia: A framework and an educational programme for enhanced action.Global Journal of Health Science,8(4), 172-187.https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n4p172

Noorman, M. A. J., den Daas, C., & de Wit, J. B. F. (2023). How parents’ ideals are offset by uncertainty and fears: A systematic review of the experiences of European parents regarding the sexual education of their children.The Journal of Sex Research,60(7), 1034-1044.https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2022.2064414

Othman, A., Shaheen, A.,Otoum, M.,Aldiqs, M., Hamad, Iqbal,Dabobe, M., Langer, A., & Gausman, J. (2020). Parent–child communication about sexual and reproductive health: Perspectives of Jordanian and Syrian parents.Sexual and Reproductive Health Matters,28(1), Article 1758444.https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1758444

Pell, T. S. (2023).Understanding approaches to parental education on sex education[Master’s Thesis, Grand Valley State University].https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/gradprojects/254/

Prabhu, S., Prabhu, S., & Noronha, F. (2023). Knowledge of child sexual abuse and attitudes towards reporting it among teachers and parents of children studying in selected primary schools of Udupi Taluk, India.Egyptian Journal of Forensic Sciences,13, Article 46.https://doi.org/10.1186/s41935-023-00365-y

Rudolph, J. I., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Straker, D.,Hambour, V., Hawes, T., & Swan, K. (2023). Parental-led sexual abuse education amongst at-risk parents: Associations with parenting practices, and parent and child symptomology.Journal of Child Sexual Abuse,32(5), 575-595.https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2023.2222116

Schneider, M., & Hirsch, J. S. (2018). Comprehensive sexuality education as a primary prevention strategy for sexual violence perpetration.Trauma, Violence and Abuse,21(3), 439-455.https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018772855

Shin, H., Lee, J. M., & Min, J. Y. (2019). Sexual knowledge, sexual attitudes, and perceptions and actualities of sex education among elementary school parents.Child Health Nursing Research,25(3), 312-323.https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2019.25.3.312

Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act,2012.(2023).https://bit.ly/44txXPO

United Nations Children’s Fund. (2016).Review of comprehensive sexuality education in Thailand. UNICEF Thailand Country Office.https://bitly.cx/XBn1Z

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2015).Comprehensive sexuality education: A global review.https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000235707

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2021).The journey towards comprehensive sexuality education: Global status report. UNESCO.https://doi.org/10.54675/NFEK1277

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2023).Republic of Korea: Comprehensive sexuality education[Global Education Monitoring Report].https://bit.ly/47VTzrj

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, UNAIDS Secretariat, United Nations Children’s Fund, UN Women, & World Health Organization. (2018).International technical guidance on sexuality education: An evidence-informed approach(2nd ed.). UNESCO.https://doi.org/10.54675/UQRM6395

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, & United Nations Population Fund. (2018).Implementation of sexuality education in middle schools in China. UNESCO, & UNFPA.https://bitly.cx/3FSBG

United Nations Population Fund, & United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2022).Comprehensive sexuality education technical guideline: Adaptation of global standards for potential use in China (first edition).https://china.unfpa.org/en/publications/22110701

United Nations Population Fund, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, & International Planned Parenthood Federation. (2020).Learn, protect, respect, empower: The status of comprehensive sexuality education in Asia and the Pacific: A summary review 2020. UNFPA.https://bitly.cx/x8aZ

United Nations Population Fund, World Health Organization, &BundeszentralefürgesundheitlicheAufklärung. (2020).Comprehensive sexuality education—Factsheet series.BundeszentralefürgesundheitlicheAufklärung,BZgA.https://bitly.cx/I6tKL

Wang, K., Xu, S. S., Liu, Z., Wang, W.,Hee, J., & Tang, K. (2023). A quasi‐experimental study on the effectiveness of a standardized comprehensive sexuality education curriculum for primary school students.Journal of Adolescence,95(8), 1666-1677.https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12235

Xie, Q. W., Qiao, D. P., & Wang, X. L. (2016). Parent-involved prevention of child sexual abuse: A qualitative exploration of parents’ perceptions and practices in Beijing.Journal of Child and Family Studies,25, 999-1010.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0277-5

Xu, W., & Cheung, M. (2023). Parental engagement in child sexual abuse prevention education in Hong Kong.Health Education Journal,82(4), 376-389.https://doi.org/10.1177/00178969231159968

Yan R., Li H., Liu Y., Zhang R., & Ye Y. (2023).农村地区家长幼儿性教育知识态度行为一致率及影响因素[Consistency and influencing factors in parents’ knowledge, attitude and practice about early childhood sex education in rural areas].Chinese Journal of School Health/中国学校卫生,44(7), 1017-1025.https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2023.07.013

Zhang, W., Ren, P., Yin, G., Li, H., & Jin, Y. (2020). Sexual abuse prevention education for preschool-aged children: Parents’ attitudes, knowledge and practices in Beijing, China.Journal of Child Sexual Abuse,29(3), 295-311.https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2019.1709240

Zhang, W., & Yuan, Y. (2023). Knowledge, attitudes, and practices of parents toward sexuality education for primary school children in China.Frontiers in Psychology,14, Article 1096516.https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1096516

Zhang X., Zhou J., Dai X., Hou F., Gao Y., Yan L., & Yuan P. (2020).四川省农村地区幼儿家庭性教育开展现状及影响因素[Young children’s family sex education in rural areas of Sichuan province and its influencing factors].Acta Academic MedicineSinicae/中国医学科学院学报,42(4), 452-458.https://doi.org/10.3881/j.issn.1000-503X.11874

Zhou Z., Yu Y., Lu L., Chen H., & Ye Y. (2022).幼儿园大班儿童性相关知信行及影响因素[Sex-related knowledge, attitude and practice and influencing factors in senior kindergarten children].Chinese Journal of School Health/中国学校卫生,43(11), 1668-1672.https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2022.11.017