Introduction

Contemporary educational reforms frequently advocate for a shift in assessment practices, moving away from traditional, selective approaches toward assessment that supports the learning process. This approach, developed in response to critiques of summative assessment, focused solely on final learning outcomes rather than the learning process itself, emphasizes the critical role of assessment in improving both learning and teaching (Berry & Adamson, 2011;FlórezPetour, 2013; Kennedy et al., 2008; Kennedy & Lee, 2008; Stobart, 2008). Although globally recommended, formative assessment initiatives, specifically assessment for learning and as learning, often face challenges in implementation, largely due to the longstanding predominance of summative assessment in educational contexts (Brownet al., 2019). The successful integration of these approaches requires a deeper understanding of teachers’ epistemological beliefs about assessment and their willingness to adopt specific roles and responsibilities in the learning and teaching process that such approaches necessitate (Brown et al., 2011; Chen & Brown, 2013). Given these considerations, examining teachers’ conceptions of assessment and their assessment practices is of great significance, not only for the effective implementation of educational reforms, but also for the enhancement of professional development programs and initial teacher education.

Assessment in education can be viewed from multiple perspectives, ranging from its role as a mechanism for quality control within the education system to its recognition as a tool for the holistic development of students (Brown et al., 2011; Li & Hui, 2007). The perspective of control and oversight highlights the significance of assessment as a key mechanism for evaluating the quality of schools and teachers, as well as for measuring student achievement against predefined educational standards. In this context, particular attention is given to the administration of standardized national examinations, primarily aimed at determining the level of quality within the education system and facilitating comparisons at local, regional, and national levels. This provides a foundation for making informed and strategic policy decisions aimed at improving teaching quality, adapting curricula, and optimizing educational standards (Brown et al., 2011). Closely related to this is the perspective that focuses on achieving predefined learning outcomes, where the primary objective is to determine the extent to which students attain these outcomes in specific curricular areas. This approach places emphasis on the objective measurement of student achievement through structured forms of assessment, with a particular focus on exam preparation and the analysis of results as indicators of instructional effectiveness. In this context, assessment is frequently employed as a means of ranking students based on their grades, facilitating comparisons of individual performance and informing decisions regarding students’ further educational pathways (Brown & Hattie, 2012). From a diagnostic and support perspective, assessment is viewed as a dynamic process that provides essential insights into student progress, strengths, and areas requiring additional support. This approach highlights the formative role of assessment, allowing teachers to adjust instructional methods, differentiate teaching, and adopt an individualized approach to students. Rather than serving solely as a tool for measuring achievement, this type of assessment functions as an instrument for continuous improvement in learning, fostering student motivation, and ensuring optimal conditions for development. A perspective focused on skill development underscores the necessity of assessing higher-order cognitive abilities, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, rather than exclusively emphasizing the reproduction of acquired knowledge. This approach promotes the use of authentic, process-oriented assessment methods, including project-based tasks, case studies, and reflective activities, which facilitate deeper comprehension and the practical application of knowledge. One of the key advantages of such assessment is its focus on preparing students for complex real-world challenges, encouraging independence, adaptability, and the ability to make well-informed decisions across different contexts. Another important perspective considers assessment as a process that plays a fundamental role in fostering students’ overall development, encompassing not only academic performance but also personal growth, social skills, and a positive attitude toward learning. This approach particularly emphasizes reflection, self-assessment, and peer assessment, enabling students to take a more active role in their own learning while recognizing their strengths and areas for improvement. Strategies such as project-based and collaborative learning are particularly highlighted, as they encourage responsibility, communication skills and teamwork, making assessment not merely a means of evaluating knowledge but also a way to enhance motivation and student engagement in the learning process. A critical perspective on assessment points to its potential drawbacks, such as result unreliability, pressure on students and the risk of diminishing motivation for learning. This perspective stresses the importance of cautious and thoughtful implementation, warning against excessive reliance on standardized testing, which may overlook individual differences among students and narrow instructional focus toward exam preparation rather than fostering deeper comprehension of subject matter.

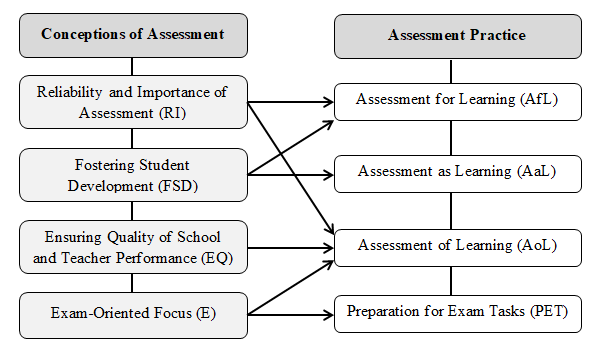

The perspectives outlined above illustrate the complexity of assessment in education and highlight the importance of applying a balanced approach that considers various aspects of learning and teaching. Figure 1 presents a conceptual framework that illustrates how specific conceptions inform dominant approaches to assessment implementation.

Figure 1. Conceptual FrameworkLinking Assessment Conceptions With Assessment Practices

Previous research on teachers’ conceptions of assessment suggests that their perceptions can be positioned along a continuum between two opposing approaches (Brownet al., 2011). At one end of the continuum is the external control perspective, which views assessment primarily as a means of monitoring and ensuring educational quality and teacher accountability. This perspective is centered on external evaluation, with the primary goal of maintaining educational standards. At the opposite end is the perspective of individual development, which perceives assessment as a tool for supporting students in their personal progress and competence development throughout the learning process. This approach emphasizes formative assessment methods that allow for the adaptation of instruction to individual student needs while promoting self-regulated learning. Studies indicate that teachers do not align exclusively with either of these extremes but rather position themselves along the continuum based on their pedagogical beliefs, professional experiences, and the specific educational context in which they work (Lin et al., 2014;Takele&Melese, 2022). Their perceptions of assessment influence not only the selection of strategies and methods but also the broader impact of assessment on students, the teaching process, and educational practice as a whole (Brown, 2008; Brown & Gao, 2015; Brown & Harris, 2009; Chen & Brown, 2013;Heitinket al., 2016; Lin et al., 2014;Takele&Melese, 2022; Toth &Csapo, 2022). Research has also shown that differences in the perception of assessment exist based on teachers’ gender and experience. Male teachers and those with extensive teaching experience are more likely to support the regulatory and institutional role of assessment, placing less emphasis on students’ personal development (Brown et al., 2010). Additionally, the school environment significantly influences teachers’ conceptions of assessment. In secondary schools, where entrance exams are critical for students’ further education and career opportunities, assessment is predominantly viewed through a regulatory and institutional lens. In contrast, in primary schools and educational settings that encourage developmental approaches to assessment, teachers are more inclined to adopt formative strategies (Brown & Gao, 2015; Brownet al., 2019).

According to research by Wang (2010, as cited in Brown & Gao, 2015), teachers can be classified into three groups based on their attitudes and approaches to assessment: active, compromise-oriented, and conflicted. Active teachers strongly advocate for student-centered assessment and personal development, rejecting external control mechanisms and the pressure associated with standardized exams. Their approach relies on formative strategies, emphasizing individual student progress, metacognitive skill development, and self-assessment. Compromise-oriented teachers acknowledge the importance of exams and standardized assessment but do not fully endorse rigid regulatory mechanisms. They strive to balance external requirements with students’ needs, blending summative and formative approaches to create equilibrium between achievement measurement and learning support. Conflicted teachers exhibit inconsistency in their views, simultaneously embracing different, often opposing, assessment concepts. Their approach varies depending on the specific context, student needs and systemic demands, leading to inconsistencies in teaching practices. These differences are particularly evident in teachers’ assessment practices. Active teachers employ a diverse range of assessment methods, encouraging students to reflect on their learning and take responsibility for their progress. Compromise-oriented teachers favor teacher-directed assessment while maintaining some level of flexibility, whereas conflicted teachers fluctuate between different approaches, assigning varying degrees of importance to different forms of assessment depending on the circumstances.

Teachers who implement diverse and developmentally oriented assessment methods contribute to better learning outcomes (Teig & Luoto, 2024). The effectiveness of formative assessment depends on multiple interrelated factors, including teachers’ beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, and skills (Black &Wiliam, 2009;Heitinket al., 2016; Yan, 2014). Given that teaching is a dynamic process in which educators apply their own conceptions of instruction and learning (Harrison, 2013; Yan, 2018), their perception of assessment plays a fundamental role in its practical implementation. Studies suggest that a positive perception of the usefulness of formative assessment correlates with teachers’ intentions to integrate it into their practice (Karaman & Sahin, 2017;So& Lee, 2011; Yan & Cheng, 2015). However, theimplementation of formative assessment is influenced not only by individual teacher attitudes but also by contextual conditions at different levels of the education system. At the micro level, classroom dynamics, available resources, and institutional support within the school can affect the frequency and effectiveness of its application (Heitinket al., 2016). At the macro level, societal pressures, educational policies, parental expectations, and internal school regulations can either facilitate or constrain teachers’ autonomy in assessment practices (Yan & Brown, 2021). These challenges are particularly pronounced in environments where summative assessment and standardized testing dominate, limiting opportunities for the adoption of formative approaches (Yin & Buck, 2019).

Schellekens et al. (2021) emphasize the importance of an integrated approach to assessment, which includes assessment for learning, assessment as learning, and assessment of learning. They argue that by connecting these concepts, it is possible to develop an assessment culture that not only measures student achievement but also actively supports their progress and the development of reflective skills. Furthermore, studies conducted in school settings indicate that assessment influences not only students’ learning but also their identity, shaping their orientation toward specific educational values and ideologies. This, in turn, has long-term effects on their perception of their own abilities and their future educational and career choices (Nieminen, 2024).

In the Croatian education system, a recent curricular reform, which resulted in the implementation of new subject curricula (Ministry of Science and Education, 2019), emphasized the importance of an individualized approach to teaching, taking into account different learning styles, interests, and student needs. One of the key elements of this reform was the shift from traditional summative assessment to formative assessment, aiming to make assessment an integral part of the instructional process, focused on providing continuous support for students’ development. Despite changes in education policy, the conceptual understanding and practical implementation of formative assessment in Croatian primary education remains insufficiently researched. Moreover, international research indicates that empirical data on the relationship between teachers’ beliefs and their classroom practices remain limited, particularly in the context of curriculum reform implementation (Yan & Brown, 2021). Given these considerations, it is justified to conduct a study examining teachers’ conceptions of assessment in Croatian primary schools, as well as the extent to which these beliefs are reflected in their teaching practices. Additionally, this research will provide insight into whether the goals of the curricular reform, particularly those related to the implementation of formative assessment, have been realized in everyday teaching and to what extent teachers embrace and apply the promoted assessment approaches. The findings of this study may offer valuable guidance for the further development of teacher professional training and the improvement of assessment strategies within the Croatian educational context.

Methodology

Research Aim and Questions

The aim of this study is to examine primary school teachers' perceptions of the nature and purpose of assessment and to determine the extent to which these conceptions are reflected in their assessment practices.

Based on this aim, the following research questions are formulated:

What is the dominant conception of the nature and purpose of assessment among primary school teachers?

To what extent do teachers, based on their self-assessment, orient their assessment practices toward formative or summative assessment?

To what extent do teachers’ conceptions of assessment explain variance in their self-evaluated assessment practices?

Is there a statistically significant relationship between teachers’ conceptions of assessment and their self-assessment of their assessment practices?

Are there statistically significant differences in assessment conceptions and self-assessed assessment practices between lower and upper primary teachers?

Are there statistically significant differences in assessment conceptions and self-assessed assessment practices based on years of teaching experience and professional status?

Sample and Data Collection

The study was conducted on a sample of 396 primary school teachers in the Republic of Croatia. The sample included 261 lower primary teachers and 135 upper primary teachers. A non-probability convenience sampling method was used, with participants recruited through online dissemination channels and existing professional teacher networks. Table 1 presents the distribution of demographic and professional variables among the participants. The analyzed variables include gender, teaching position (lower or upper primary teacher), professional title, and years of teaching experience (Table 1).

Table 1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents

| Variable | Rank | N | % |

| Gender | male | 31 | 7.8 |

| female | 365 | 92.2 | |

| Teaching position | lower primary | 261 | 65.9 |

| upper primary | 135 | 34.1 | |

| Years of teaching experience | 0-5 years | 50 | 12.6 |

| 6-10 years | 35 | 8.8 | |

| 11-15 years | 45 | 11.4 | |

| 16-20 years | 58 | 14.6 | |

| more than 20 years | 208 | 52.5 | |

| Professional status | teacher | 280 | 70.7 |

| mentor teacher | 56 | 14.1 | |

| teacher advisor | 43 | 10.9 | |

| distinguished teacher advisor | 17 | 4.3 |

The sample of 396 teachers from 20 counties ensured broad geographical representation, thereby achieving sample diversity. The most represented regions were Osijek-Baranja County (28.3%), the City of Zagreb (23.2%), and Split-Dalmatia County (13%). Among the respondents, 31 were male (7.8%), while the remaining 92.2% were female. The sample is predominantly female (92.2%), reflecting national trends in Croatian primary education. However, this may limit generalizability to male teachers, whose assessment conceptions or practices may differ. The sample consisted of 65.9% lower primary teachers and 34.1% upper primary teachers. An analysis of teaching experience revealed that the most significant proportion of teachers had more than 20 years of experience (52.5%), while 14.6% had between 16 and 20 years. Teachers with 11 to 15 years of experience accounted for 11.4%, those with 6 to 10 years made up 8.8%, and early-career teachers with 0 to 5 years of experience constituted 12.6% of the sample. Regarding professional advancement, the majority of participants held no additional professional titles (70.7%). A total of 14.1% had attained the title of mentor teacher, while 10.9% were advisor teachers. The most advanced category, distinguished advisor teachers, accounted for 4.3% of the sample.

Data for this study were collected using an online survey questionnaire, created via the Google Forms platform. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, with respondents being informed in advance about the research objectives and their right to withdraw at any time. This ensured adherence to ethical research standards, including informed consent and privacy protection.

The questionnaire consisted of two sections: an assessment of conceptions and a self-assessment of teaching practices, along with an introductory section containing demographic information.

Teachers’ conceptions of assessment were examined using an adapted version of theTeachers’ Conceptions and Practices of Assessment in Chinese Contexts questionnaire(Brownetal., 2011). The questionnaire contained 48 statements rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 – strongly disagree to 5 – strongly agree), organized into four subscales that explored different conceptions of the nature and purpose of assessment in education:

a)Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) explores teachers’ attitudes toward the objectivity, reliability and importance of assessment. It includes statements related to evaluating the accuracy and fairness of the assessment process.

b)Fostering Student Development (FSD) addresses teachers’ attitudes toward the importance of assessment in the learning process, focusing on fostering student progress, development and holistic growth.

c)Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) examines teachers’ attitudes toward assessment as a tool for monitoring and improving the quality of school and teacher performance, emphasizing institutional accountability for maintaining high educational standards.

d)Exam-Oriented Focus (E) evaluates teachers' views on assessment's role in exam preparation and success.

The self-assessment of teaching assessment practices was conducted using a questionnaire based onThe Practices of Assessment Inventory(Brownetal., 2009). The questionnaire consisted of 34 statements distributed across four subscales:

a)Assessment for Learning (AfL) examines the frequency of using assessment methods that support the learning process and provide feedback to students aimed at improving the learning process.

b)Assessment as Learning (AaL) explores the frequency of applying assessment strategies that encourage students to engage in self-assessment and reflection on their own learning.

c)Assessment of Learning (AoL) examines the use of assessment for evaluating outcomes and performance.

d)Preparation for Exam Tasks (PET) assesses the frequency of using strategies aimed at preparing students for standardized exams.

Teachers self-assessed the frequency of using these assessment methods on a five-point scale, where they rated how often they implemented each strategy (1 – very rarely, 5 – very frequently).To assess the reliability of the adapted scales, internal consistency was examined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, all of which demonstrated acceptable to high levels of reliability (see Table X).

For statistical analysis, two composite variables were created: formative assessment (FOR), combiningAfLandAaL, and summative assessment (SUM), based onAoLand PET.

The original instruments by Brownetal.(2009, 2011) were translated into Croatian using a forward–backward procedure. Minor linguistic and contextual adaptations were made to ensure conceptual equivalence and alignment with national curricular terminology.

Analyzing of Data

Statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS 20 statistical software package. The normality of distribution for all variables was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Parametric statistical procedures were applied in the subsequent data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to determine teachers’ conceptions of the nature and purpose of assessment and to examine the extent to which their teaching practices align with formative or summative assessment approaches. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to assess the relationship between assessment conceptions and assessment practices, specifically examining the correlation between responses on different scales. Regression analysis was conducted to explore the association between teachers’ perceptions of assessment and their actual assessment practices. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to identify differences in responses based on demographic characteristics. The reliability of all scales used in the study was evaluated by calculating Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient.

Results

The descriptive statistical analysis presented in Table 2 indicates that skewness and kurtosis deviations were relatively low, and the result distributions were generally symmetrical, exhibiting slight positive or negative asymmetry. Therefore, parametric statistical procedures were applied in further analysis. The results of the Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient indicate borderline reliability for the Assessment of Learning (AoL) scale, very good reliability for the Preparation for Exam tasks (PET) and Summative Assessment (SUM) scales, and excellent reliability for all other variables.

Table 2.Descriptive Statistic

| M | C | D | SD | Skew | Kurt | Min | Max | KS | α | |

| RI total | 45.9 | 47.0 | 49.0 | 8.96 | -0.22 | 0.03 | 21 | 68 | 0.06** | .88 |

| FSD total | 52.5 | 53.0 | 57.0 | 10.94 | -0.47 | 0.53 | 15 | 75 | 0.08** | .94 |

| EQ total | 30.6 | 31.0 | 29.0 | 7.21 | -0.16 | 0.32 | 10 | 50 | 0.08** | .87 |

| E total | 17.6 | 18.0 | 19.0 | 3.74 | -0.56 | 0.84 | 5 | 25 | 0.09** | .84 |

| AfL total | 44.1 | 44.0 | 48.0 | 7.13 | -0.32 | 0.18 | 23 | 60 | 0.06** | .81 |

| AaL total | 22.5 | 23.0 | 24.0 | 4.56 | -0.65 | 0.34 | 6 | 30 | 0.10** | .84 |

| PET total | 32.4 | 33.0 | 35.0 | 4.96 | -0.89 | 0.68 | 15 | 40 | 0.11** | .76 |

| AoL total | 28.1 | 28.0 | 28.0 | 4.65 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 15 | 40 | 0.07** | .63 |

| FOR total | 66.6 | 67.0 | 63.0 | 11.01 | -0.41 | 0.26 | 29 | 90 | 0.05* | .89 |

| SUM total | 60.5 | 67.0 | 61.0 | 7.91 | -0.48 | 0.68 | 31 | 80 | 0.07** | .76 |

| RI mean | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 0.60 | -0.22 | 0.03 | 1 | 5 | 0.06** | |

| FSD mean | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.8 | 0.73 | -0.47 | 0.53 | 1 | 5 | 0.08** | |

| EQ mean | 3.1 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 0.72 | -0.16 | 0.32 | 1 | 5 | 0.08** | |

| E mean | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 0.75 | -0.56 | 0.84 | 1 | 5 | 0.09** | |

| AfL mean | 3.7 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 0.59 | -0.32 | 0.18 | 2 | 5 | 0.06** | |

| AaL mean | 3.8 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 0.76 | -0.65 | 0.34 | 1 | 5 | 0.10** | |

| AoL mean | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 0.58 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 2 | 5 | 0.07** | |

| PET mean | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 0.62 | -0.89 | 0.68 | 2 | 5 | 0.11** | |

| FOR mean | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 0.61 | -0.41 | 0.26 | 2 | 5 | 0.05* | |

| SUM mean | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.49 | -0.48 | 0.68 | 2 | 5 | 0.07** |

Legend: RI - Reliability and Importance of Assessment, FSD - Fostering Student Development, EQ - Ensuring the Quality of Schools and Teachers, E - Exam-Oriented Focus,AfL– Assessment for Learning,AaL– Assessment as Learning, PET - Preparation for Exam Tasks,AoL– Assessment ofLeraning, FOR – Formative Assessment, SUM – Summative Assessment,M– Mean,C– Median,D– Mode,SD– Standard Deviation, Skew – Skewness, Kurt – Kurtosis, Min – Minimum, Max – Maximum, KS – Kolmogorov-Smirnov test for normality, α – Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient, * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Perceived Nature and Purpose of Assessment and Self-Assessment of Evaluation

The mean scores of participants’ responses indicate an ambivalent stance among teachers regarding the reliability and importance of assessment in the educational process (RI) (M= 3.1,SD= 0.60), as well as its role in ensuring, monitoring and improving the quality of schools and teaching (EQ) (M= 3.1,SD= 0.72). At the same time, teachers support the conception that emphasizes the role of assessment in fostering the learning process and student development (FSD) (M= 3.5,SD= 0.73). However, the findings also suggest that assessment is not perceived solely as a tool for improving learning but also as a means of achieving external goals and measurable outcomes. A moderately positive stance on the importance of assessment in preparing students for standardized exams and ensuring success in testing (E) (M= 3.5,SD= 0.75) further highlights the presence of a summative assessment perspective.

Self-Assessment of Teachers on the Frequency of Using Different Assessment Strategies

Teachers’ self-assessment of the frequency of applying different assessment strategies further supports this duality. While formative assessment strategies (FOR) are relatively frequently used (M= 3.7,SD= 0.61), including providing feedback and tracking student progress (AfL) (M= 3.8,SD= 0.59), as well as self-assessment and peer assessment (AaL) (M= 3.7,SD= 0.76), strategies focused on exam preparation (PET) remain significantly more prominent in their teaching practices (M= 4.1,SD= 0.62). These findings indicate that despite recognizing the importance of formative assessment, preparing students for exams continues to be a key aspect of teachers' practice.

To examine differences within the Assessment Conceptions scale, a repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted, revealing statistically significant differences among the four subscale mean scores (F(3.395) = 280.27;p< .01) (Table 3).

| M | RI mean | FSD mean | EQ mean | E mean | |

| RI mean | 3.1 | MD = -.44, p < .01 | MD = -.00, p > .05 | MD = -.46, p < .01 | |

| FSD mean | 3.5 | MD = .44, p < .01 | MD = .02, p > .05 | ||

| EQ mean | 3.1 | MD = -.46, p < .01 | |||

| E mean | 3.5 |

Legend:M– arithmetic mean,MD– difference in arithmetic means, p– probability of error

Data presented in Table 3 indicate that the highest mean scores (M= 3.5) were observed on the subscales measuring the perception of assessment as a tool for fostering student development (FSD) and the conceptual orientation toward exam preparation (E) (MD= .02,p> .01). The results for both variables significantly differ from the mean scores on the Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) scale (MD= .44,p< .01;d= 0.66for FSD - RI;MD= .46,p< .01;d= 0.68for E - RI) and the Assessment as a Means of Quality Assurance in Schools and Teaching (EQ) scale (MD= .44,p< .01;d= 0.61for FSD - EQ;MD= .46,p< .01;d= 0.68for E - EQ), where the mean values were M = 3.1. Cohen’s d values for significant differences ranged from 0.61 to 0.68, indicating medium to large effect sizes. These differences remained statistically significant after applying the Bonferroni correction (adjusted α = .0083). No statistically significant difference was found between perceptions of Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) and Ensuring Educational Quality in Schools and Teaching (EQ) (MD= .00,p> .05).

| M | AfL mean | AaL mean | AoL mean | PET mean | |

| AfL mean | 3.7 | MD = -.07, p < .05 | MD = .16, p < .01 | MD = -.38, p < .01 | |

| AaL mean | 3.8 | MD = .23, p < .01 | MD = -.31, p < .01 | ||

| AoL mean | 3.5 | MD = -.54, p < .01 | |||

| PET mean | 4.1 |

Legend:M– arithmetic mean,MD– difference in arithmetic means,p– probability of error

In this analysis, all pairwise differences were found to be statistically significant. It can be concluded that teachers achieve the highest scores on theAssessment Practicesscale on thePreparation for Exams(PET) subscale (M = 4.1), which is statistically significantly higher than the scores on theAssessment for Learning(AfL) subscale (MD= .38,p< .01;d= 0.63), theAssessment as Learning(AaL) subscale (MD= .31,p< .01;d= 0.45), and theAssessment of Learning(AoL) subscale (MD= .54,p< .01;d= 0.87). It was also found thatAssessment of Learning(AoL) has a statistically significantlylower score (M= 3.5) compared toAssessment for Learning(AfL) (MD= .16,p< .01;d= 0.27) andAssessment as Learning(AaL) (MD= .23,p< .01;d= 0.34).

Within formative assessment, the mean score for Assessment as Learning (AaL) (M= 3.8) was significantly higher (MD= -.07,p< .05;d= 0.14) than that for Assessment for Learning (AfL) (M= 3.7). Within summative assessment, the mean score on the Exam Preparation (PET) scale (M= 4.1) was significantly higher (MD= .31,p< .01;d= 0.45) than that on the Assessment of Learning (AoL) scale (M= 3.5). The effect sizes ranged from very small to large (Cohen’s d = 0.14–0.87), indicating varying degrees of practical significance across the comparisons. Most pairwise differences remained statistically significant after applying the Bonferroni correction (adjusted α = .0083), except for the comparison betweenAfLandAaL.

To determine whether a statistically significant difference exists in the self-assessed frequency of applying formative and summative assessment, a paired-samples t-test was conducted. The results of the t-test indicated that the mean scores on the Assessment Practices scales differed significantly (t(396) = 2.68,p< .01;d= 0.14), with summative assessment being more frequently applied than formative assessment.

Predictive Value of Individual Assessment Conceptions on Specific Assessment Practices

To examine the predictive value of specific assessment conceptions (RI, FSD, EQ, E) for specific assessment practices (AaL, AfL, AoL, PET),four regression analyses were conducted, using the assessment conceptions(RI, FSD, EQ, E) as predictors and the assessment practices (AaL, AfL, AoL, PET) as criteria. Additionally,two regression analyseswere performed where summative (SUM) and formative (FOR) assessments were used as criteria.

Before conducting the regression analyses, the necessary assumptions were tested. This included analyzing correlations among variables, residual autocorrelation, multicollinearity,and the presence of outliers. Table 5. presents the correlation matrix for all six regression analyses.

Table 5. Intercorrelations Among Predictors and Correlations Between Predictors and Criteria

| RI | FSD | EQ | E | AfL | AaL | PET | AoL | FOR | SUM | |

| RI total | 1 | .87** | .79** | .79** | .32** | .27** | .08 | .22** | .32** | .18** |

| FSD total | 1 | .80** | .89** | .37** | .35** | .15** | .25** | .38** | .24** | |

| EQ total | 1 | .77 | .30** | .26** | .13** | .29** | .31** | .25** | ||

| E total | 1 | .37** | .35** | .18** | .24** | .38** | .26** | |||

| AfL total | 1 | .76** | .41** | .54** | .57** | |||||

| AaL total | 1 | .40** | .45** | .51** | ||||||

| PET total | 1 | .36** | .43** | |||||||

| AoL total | 1 | .53** | ||||||||

| FOR total | 1 | .59** | ||||||||

| SUM total | 1 |

Legend:*p< 0.05; **p< 0.01

As shown in Table 5, all predictors demonstrated weak to moderate correlations with the criterion variable (r = .13 – .38), except for the correlation between Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) and Preparation for Exams (PET) (r = .08, p > .05). Despite this lack of correlation, Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) was later included in the regression analysis for predicting Preparation for Exams (PET). Additionally, the predictors were correlated with each other; however, none of the correlations exceeded .90, which would indicate redundancy and suggest that the items measure the same construct. Therefore, all predictors were retained in the analysis.

Residual autocorrelation and multicollinearity diagnostics are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.Measures of Residual Autocorrelation (Durbin-Watson) and Multicollinearity (VIF and Tolerance)

| Durbin Watson | tolerance | VIF | |

| RI total | 2.013 - 2.097 | .217 | 4.607 |

| FSD total | .133 | 7.493 | |

| EQ total | .312 | 3.203 | |

| E total | .206 | 4.863 |

The Durbin-Watson statistic, as expected, is approximately 2, indicating no significant autocorrelation in the residuals. Multicollinearity diagnostics show acceptable tolerance values, all above 0.1. However, variance inflation factor (VIF) values exceed 4, indicating a degree of multicollinearity due to high correlations among predictors.

Regarding outliers, they were removed prior to all analyses, ensuring that they did not influence the obtained results.

Table 7.Contribution of the Results of Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI), Fostering Student Development (FSD), Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) and Exam-Oriented Focus (E)in Explaining Self-Assessment of Assessment for Learning (AfL), Assessment as Learning (AaL), Assessment of Learning (AoL), Preparation for Exams (PET), Formative Assessment (FOR), and Summative Assessment (SUM)

| V | Β | t | p | |

| CRITERION: ASSESSMENT FORLEARNING (AfL) | 15% | |||

| Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) | -.02 | -.24 | > .05 | |

| Fostering Student Development (FSD) | .23 | 1.78 | > .05 | |

| Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) | .00 | .02 | > .05 | |

| Exam-Oriented Focus (E) | .18 | 1.78 | > .05 | |

| R = .381; R2 = .145; Adapted R2 = .136; ∆F(4/391) = 16.57; p < .01 | ||||

| CRITERION: ASSESSMENT AS LEARNING (AaL) | 13% | |||

| Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) | -.11 | -1.09 | > .05 | |

| Fostering Student Development (FSD) | .29 | 2.28 | < .05 | |

| Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) | -.05 | -.53 | > .05 | |

| Exam-Oriented Focus (E) | .21 | 1.99 | < .05 | |

| R = .363; R2 = .132; Adapted R2 = .123; ∆F(4/391) = 14.51; p < .01 | ||||

| CRITERION: ASSESSMENT OF LEARNING (AoL) | 9% | |||

| Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) | -.08 | -.79 | > .05 | |

| Fostering Student Development (FSD) | .06 | .42 | > .05 | |

| Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) | .28 | 3.26 | < .01 | |

| Exam-Oriented Focus (E) | .04 | .40 | > .05 | |

| R = .297; R2 = .088; Adapted R2 = .079; ∆F(4/391) = 9.47; p < .01 | ||||

| CRITERION: PREPARATION FOR EXAM TASKS (PET) | 5% | |||

| Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) | -.25 | -2.31 | <.05 | |

| Fostering Student Development (FSD) | .13 | .991 | > .05 | |

| Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) | .06 | .62 | > .05 | |

| Exam-Oriented Focus (E) | .22 | 1.98 | < .05 | |

| R = .217; R2 = .047; Adapted R2 = .037; ∆F(4/391) = 4.81; p < .05 | ||||

| CRITERION: FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT (FOR) | 16% | |||

| Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) | -.06 | -.62 | > .05 | |

| Fostering Student Development (FSD) | .27 | 2.12 | < .05 | |

| Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) | -.02 | -.21 | > .05 | |

| Exam-Oriented Focus (E) | .21 | 2.00 | < .05 | |

| R = .396; R2 = .157; Adapted R2 = .18; ∆F(4/391) = 18.16; p < .01 | ||||

| CRITERION: SUMMATIVE ASSESSMENT (SUM) | 8% | |||

| Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) | -.20 | -1.95 | > .05 | |

| Fostering Student Development (FSD) | .12 | -.88 | > .05 | |

| Ensuring Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) | .20 | 2.31 | < .05 | |

| Exam-Oriented Focus (E) | .16 | 1.50 | > .05 | |

| R = .288; R2 = .083; Adapted R2 = .074; ∆F(4/391) = 8.87; p < .01 |

Legend: R – multiple correlation coefficient, R² – multiple determination coefficient, V – percentage of explained variance.* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

The results of the regression analysis, presented in Table 7, indicate that all regression coefficients are statistically significant. The percentage of explained variance is highest for Assessment for Learning (AfL) (15%) and Assessment as Learning (AaL) (13%) among individual variables, with a higher explained variance for Formative Assessment (FOR) (16%) compared to Summative Assessment (SUM) (8%).However, a review of the beta weights reveals that not all analyses include statistically significant predictors. No significant predictor was found for Assessment for Learning (AfL), despite its highest regression coefficient. For Assessment as Learning (AaL), significant predictors include Fostering Student Development (FSD) (β = .29,t= 2.28,p< .05) and Exam-Oriented Assessment (E) (β = .21, t = 1.99, p < .05). For Assessment of Learning (AoL), Ensuring the Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ) was a significant predictor (β = .28,t= 3.26,p< .01). For Exam Preparation (PET), significant predictors were Reliability and Importance ofAssessment (RI) (β = - .25,t= -2.31,p< .05) and Exam-Oriented Assessment (E) (β = .22,t= 1.98,p< .05). In Formative Assessment (FOR), significant predictors were Fostering Student Development (FSD) (β = .27,t= 2.12,p< .05) and Exam-Oriented Assessment (E) (β = .21, t = 2.00, p < .05). Finally, for Summative Assessment (SUM), Quality Assurance in Schools and Teaching (EQ) was a significant predictor (β = .20,t= 2.31,p< .05).

Fostering Student Development (FSD), Ensuring the Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ),andExam Orientation (E)were identified as positive predictors. Higher scores on Fostering Student Development (FSD) were associated with increased scores on Assessment as Learning (AaL) and Formative Assessment (FOR). Higher scores on Exam-Oriented Assessment (E) were linked to increased scores on Exam Preparation (PET). Additionally, with higher results on theEnsuring the Quality of School and Teacher Performance (EQ)variable, theAssessment of Learning (AoL)andSummative Assessment (SUM)criteria also increase.Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) was found to be a negative predictor, indicating that higher scores on this variable were associated with lower scores in the Preparation for Exam Tasks (PET) criterion variable.

Differences in Perceptions of Assessment and Self-assessment of Assessment Practices Based on Demographic Characteristics

To examine whether statistically significant differences exist in perceptions of assessment and assessment practices based on demographic and professional characteristics (years of experience, professional title and teaching position), one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were conducted.

First, differences in the examined variables were analyzed in relation to participants’ years of teaching experience (Table 8).

Table 8. Results of Testing Variance Homogeneity Using Levene's Test for Testing Differences Based on Years of Experience

| Levene's statistic | df1 | df2 | p | |

| RI mean | 0.66 | 4 | 391 | > .05 |

| FSD mean | 0.35 | 4 | 391 | > .05 |

| EQ mean | 0.20 | 4 | 391 | > .05 |

| E mean | 0.08 | 4 | 391 | > .05 |

| AfL mean | 2.87 | 4 | 391 | < .01 |

| AaL mean | 3.24 | 4 | 391 | < .01 |

| AoL mean | 0.30 | 4 | 391 | > .05 |

| PET p mean | 1.37 | 4 | 391 | > .05 |

| FOR mean | 3.28 | 4 | 391 | < .01 |

| SUM mean | 0.43 | 4 | 391 | > .05 |

Legend:df– degrees of freedom,p– probability of error

Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances was found to be statistically significant for the variables Assessment as Learning (AaL) (LS(4,391) = 2.87, p < .01), Assessment for Learning (AfL) (LS(4,391) = 3.24, p < .01), and Formative Assessment (FOR) (LS(4,391) = 3.28, p < .01). Consequently, instead of ANOVA, a robust Welch test was applied for these variables (Table 9).

Table 9. Results of One-Way ANOVA and WELCH Test for Testing Differences Based on Work Experience

| F/W | p | |

| RI mean | 1.76 | > .05 |

| FSD mean | 3.08 | < .05 |

| EQ mean | 1.90 | > .05 |

| E mean | 3.80 | < .01 |

| AfL mean | 1.51 | > .05 |

| AaL mean | 1.88 | > .05 |

| AoL mean | 1.26 | > .05 |

| PET p mean | 1.73 | > .05 |

| FOR mean | 1.69 | > .05 |

| SUM mean | 1.75 | > .05 |

Legend:F– F ratio,p– probability of error

The obtained results indicate two statistically significant differences in the measured variables based on teachers’ years of experience: Fostering Student Development Promotion (FSD) (F= 3.08,p< .05) and Exam-Oriented Assessment (E) (F= 3.80,p< .01). SeparateScheffétests reveal that for Fostering Student Development (FSD), it was not possible to detectsignificant differences between individual groups. This is likely due to the strict nature ofScheffé’stest as well as the borderline significance of the F-ratio in the analysis of variance.

On the other hand, for theExam Orientation (E)variable, a single significant difference was identified between the group with 11 to 15 years of experience and the group with more than 20 years of experience. The results show that teachers withmore than 20 years of experience(M = 3.6, SD= 0.73) scored higher on theExam Orientation (E)variable compared to those with11 to 15 years of experience(M= 3.2,SD= 0.75).

Regarding the analysis of differences based on teachers’ professional status, Levene’s test was not statistically significant (Table10), supporting the use of a one-way ANOVA.

Table 10. Results of Testing Variance Homogeneity Using Levene's Test for Testing Differences Based on Professional Rank

| Levene's statistic | df1 | df2 | p | |

| RI mean | 0.04 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| FSD mean | 0.23 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| EQ mean | 0.61 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| E mean | 0.05 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| AfL mean | 0.77 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| AaL mean | 0.73 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| AoL mean | 0.48 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| PET p mean | 0.43 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| FOR mean | 0.42 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

| SUM mean | 0.24 | 3 | 392 | > .05 |

Legend:df– degrees of freedom,p– probability of error

The results of theANOVAare presented inTable 11.

Table 11. Results of the One-Way ANOVA Testing Differences Based on Professional Rank

| F | p | |

| RI mean | 2.38 | > .05 |

| FSD mean | 2.11 | > .05 |

| EQ mean | 1.86 | > .05 |

| E mean | 0.75 | > .05 |

| AfL mean | 5.43 | < .01 |

| AaL mean | 4.07 | < .01 |

| AoL mean | 1.10 | > .05 |

| PET p mean | 0.58 | > .05 |

| FOR mean | 5.27 | < .01 |

| SUM mean | 0.75 | > .05 |

Legend:F– F ratio,p– probability of error

The results in the table above show that there is a statistically significant difference in the results for the variablesAssessment for Learning (AfL)(F(3/292) = 5.43,p< .01),Assessment as Learning (AaL)(F(3/292) = 4.07,p< .01), andFormative Assessment (FOR)(F(3/292) = 5.27,p< .01) based on teachers' professional rank. In all three cases, the difference was found only between teachers and mentor teachers, with mentor teachers scoring higher on Assessment for Learning (AfL) (M= 3.9,SD= 0.54), Assessment as Learning (AaL) (M= 4.0,SD= 0.66), and Formative Assessment (FOR) (M= 4.0,SD= 0.56) compared to teachers, who had lower mean scores on these variables (M= 3.6,SD= 0.59; M = 3.7,SD= 0.77; andM= 4.6,SD= 0.64).

To examine differences based on teaching position, an independent samples t-test was conducted (Table 12).

Table 12. Results of the t-Test for Testing Differences Based on Teaching Position

| t | p | Mlow | Mupp | |

| RI mean | -0.25 | > .05 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| FSD mean | 0.26 | > .05 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| EQ mean | -1.89 | > .05 | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| E mean | -0.46 | > .05 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| AfL mean | 3.58 | < .01 | 3.7 | 3.5 |

| AaL mean | 3.72 | < .01 | 3.9 | 3.5 |

| AoL mean | 5.03 | < .01 | 3.6 | 3.3 |

| PET p mean | -1.45 | > .05 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| FOR mean | 4.01 | < .01 | 3.8 | 3.5 |

| SUM mean | 1.97 | > .05 | 3.8 | 3.7 |

Legend:t– t-test,p– probability of error,Mlow– mean for lower primary teachers,Mupp– mean for upper primary subject teachers.

The results presented in Table 12indicate a statistically significant difference in scores for the variables Assessment for Learning (AfL) (t(394) = 3.58,p< .01), Assessment as Learning (AaL) (F(239.41) = 3.72,p< .01), Assessment of Learning (AoL) (t(394) = 5.03,p< .01) and Formative Assessment (FOR) (F(394) = 4.01,p< .01), depending on teachers' occupation (teaching position). In all four cases, lower primary teachers achieved higher scores than upper primary teachers.

Discussion

This study examined teachers’ conceptions and practices of assessment among primary school teachers. The findings indicate an almost equal representation of two dominant conceptions: one that views assessment as a tool for fostering student learning and development, and another that emphasizes its role in preparing students for exams. This dual perspective is also reflected in teachers’ assessment practices. The results suggest that, although most teachers nominally prefer formative assessment as a means of supporting student development, they still rely significantly on traditional summative assessment methods. This reliance may not always reflect teacher preference but rather the pressure to conform to school-wide norms, assessment policies, and parental expectations. In such settings, formative strategies may be deprioritized in favor of practices that align more closely with external accountability demands, even when teachers personally endorse developmental approaches. According to the classification proposed by Wang (2010, as cited in Brown & Gao, 2015), this pattern aligns with the compromise-oriented teacher group, which seeks to balance formative assessment aimed at student growth with summative assessment as a mechanism for evaluating achievement and maintaining educational standards. These patterns align with Brown et al.’s (2011) model, which situates teacher beliefs on a continuum from control-oriented to developmentally supportive approaches. The coexistence of formative and summative practices suggests that Croatian teachers navigate this continuum dynamically, adapting their assessment use based on contextual demands. They attempt to integrate summative and formative assessment to meet institutional requirements while also supporting students’ development. Such a compromise approach may be influenced by educational policies, school regulations, societal expectations and the external pressures associated with standardized assessment. Although often criticized for promoting surface learning and limiting student agency, summative assessment plays key roles in standardization, accountability, and providing measurable indicators for reporting and policy (Black & Wiliam, 2009; Brown et al., 2011). Recognizing these systemic functions helps contextualize teachers’ use of summative strategies as a pragmatic response to institutional and curricular demands. Despite recognizing the benefits of formative assessment, teachers may encounter barriers to its systematic implementation, such as large class sizes, time constraints, and a lack of professional support for applying formative strategies.

The results of the regression analysis confirm a significant relationship between teachers’ conceptions of assessment and their assessment practices. The highest explained variance was observed for Assessment for Learning (AfL) (15%) and Assessment as Learning (AaL) (13%), while Formative Assessment (FOR) (16%) had a higher explained variance than Summative Assessment (SUM) (8%). These findings suggest that teachers’ beliefs about assessment are more strongly linked to formative than to summative approaches, which aligns with reform guidelines aimed at supporting learning.

Despite the high regression coefficient for Assessment for Learning (AfL), no statistically significant predictor was identified, pointing to the concept’s complexity and its reliance on multiple interacting factors. Teachers may understand and applyAfLdifferently, ranging from general support to structured strategies, while external pressures such as institutional demands, curriculum constraints, and standardized testing can weaken the link between beliefs and practice. Social desirability bias in self-reports may also have affected the results. Among the significant predictors, Fostering Student Development (FSD) positively predicted both Assessment as Learning (AaL) and Formative Assessment (FOR), suggesting that teachers who perceive assessment as a tool for student development are more likely to use reflective and learning-supportive strategies. This finding is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Black &Wiliam, 2009;Heitinket al., 2016), which have shown that teachers with developmentally oriented beliefs tend to use assessment not only for evaluation but also for enhancing learning.This supports the view that assessment practices stem from teachers’ epistemological beliefs, with developmental conceptions promoting more student-centered approaches (Chen & Brown, 2013).

On the other hand, Exam-Oriented Assessment (E) positively predicted Exam Tasks Preparation (PET), which is expected, as teachers who primarily view assessment as a means of measuring student achievement tend to adopt strategies that prepare students for standardized testing. This finding suggests that an exam-focused assessment culture remains a significant element of teaching practice, despite ongoing reform efforts aimed at strengthening formative assessment. Interestingly, Ensuring the Quality of Schools and Teachers (EQ) emerged as a significant predictor of Assessment of Learning (AoL) and Summative Assessment (SUM). This aligns with the accountability-oriented conception described by Brown et al. (2011), which emphasizes institutional purposes and external evaluation. In contrast, Reliability and Importance of Assessment (RI) was found to be a negative predictor of Exam Preparation (E), suggesting that teacherswho consider assessment to be reliable and significant place less emphasis on exam preparation. This unexpected finding suggests that teachers may not associate assessment reliability with exam rigor or standardized testing, but with the consistent use of formative strategies. Here, reliability is grounded in clear criteria, ongoing monitoring, and a focus on learning rather than exam preparation (Chen & Brown, 2013).

These findings highlight the crucial role of teachers’ beliefs in shaping their assessment practices and suggest that teachers often combine formative and summative approaches. While some elements of assessment for learning and formative assessment are strongly present, the persistent importance of exams and summative strategies indicates that the transition to a fully reformed assessment model has not yet been fully realized in practice.

Teaching experience also emerged as a relevant factor in assessment practices. Teachers with longer experience demonstrated a stronger orientation toward exam-focused assessment, indicating a preference for traditional assessment approaches. Since these teachers completed their formal teacher education more than 20 years ago, it is evident that they have retained the traditional assessment methods that were dominant at that time. This finding raises the question of the need for continuous professional development to ensure the effective implementation of contemporary assessment approaches, particularly formative assessment, which have been shown to have a significant positive impact on student development (Granberg et al., 2021; Harris et al., 2022).

Teachers' professional rank was also found to be significant in shaping their assessment practice. Mentor teachers scored significantly higher on Assessment for Learning (AfL), Assessment as Learning (AaL) and Formative Assessment (FOR) compared to teachers without a mentor title. This suggests a positive influence of the mentoring role on the development of formative assessment practices. Mentors are often engaged in additional training and professional and academic activities, deepening their understanding of assessment’s purpose and nature which may facilitate the implementation of innovative assessment strategies. Additionally, their position may grant them greater autonomy and institutional support, which are crucial for sustained use of formative approaches. These findings align with the conclusions of Xu and Brown (2016), who emphasized the role of professional development in strengthening teachers’ assessment literacy.

An independent samples t-test showed that lower primary teachers scored significantly higher on variables related to formative assessment, assessment for learning, and assessment as learning compared to upper primary teachers. This difference may be attributed to the specific characteristics of lower primary education, which inherently promotes a holistic approach to learning and assessment (Monteiro et al.,2021). Lower primary teachers in Croatia typically work with a smaller group of students (15 – 28 students) and teach all subjects within their class (except for foreign language and religious education). This holistic approach allows them to gain a deeper understanding of individual student needs and progress, facilitating the use of formative assessment. By its nature, formative assessment requires continuous monitoring, feedback provision, and instructional adjustments based on students' needs. In lower primary education, teachers have greater opportunities to integrate these approaches. Additionally, lower primary classrooms often cultivate a collaborative learning environment, where students work on projects, share ideas and support each other. This setting is highly conducive to peer assessment and feedback exchange. Moreover, working with fewer students enables lower primary teachers to dedicate more time to individualized instruction, which is crucial for the effective implementation of formative assessment. Conversely, upper primary teachers face several challenges in implementing formative assessment. They work with a larger number of students for shorter periods, which limits the ability to individualize instruction and provide continuous progress monitoring - key components of formative assessment. The primary focus often shifts toward covering curriculum outcomes within a limited time frame, leaving less flexibility for adjusting instruction based on formative assessment feedback.Upper primary education is frequently subject-centered, emphasizing the acquisition of specific knowledge and skills within each discipline. This focus can lead to greater reliance on summative assessment, as it provides a structured way to verify student achievement. Teachers may also feel pressure to prepare students for secondary school admissions, which can further reduce motivation for implementing formative assessment.Additionally, contextual factors, such as school culture, may further limit the use of formative assessment strategies.

Previous research has shown that teachers’ assessment approaches and beliefs significantly impact student learning, motivation, and socio-emotional well-being (Van Orman et al., 2024). Some studies also highlight that the actual implementation of formative assessment remains far below expectations (Berry & Adamson, 2011; Yan & Brown, 2021). A clear understanding of the factors that facilitate or hinder the use of formative assessment from teachers’ perspectives can help researchers and policymakers design support measures that promote its more frequent and effective application in teaching practices (Yan et al., 2021).

Conclusion

The findings of this study provide insight into the complexity of teachers' conceptions and assessment practices in primary schools, highlighting the importance of continuous professional development and the need for more frequent integration of formative assessment approaches in upper primary education (grades 5–8). Additionally, it is essential to further develop specialized professional development programs, such as those involving mentor teachers, given their statistically higher use of formative assessment practices compared to teachers who have not advanced to mentor status. Moreover, it is necessary to examine the potential reasons for the observed differences between lower and upper primaryteachers in order to design assessment approaches that align with the specific demands of both educational contexts, particularly those relevant to upper primary teaching. While statistically significant differences in assessment conceptions were identified based on teachers' years of experience, further research with larger and more representative samples is needed to confirm these findings and clarify their practical significance. A key priority should be the provision and evaluation of professional development programs that empower teachers to employ modern assessment approaches, promoting formative assessment as a concept that can enhance student learning and raise overall learning outcomes. In this context, it is necessary to develop practical tools and resources that facilitate the implementation of formative assessment in the classroom. These could include task examples, assessment rubrics, digital tools for tracking student progress and guidelines for providing feedback. The study by Wyatt-Smith et al. (2024) demonstrated that teacher feedback is not merely a tool for correcting mistakes or assigning grades but a fundamental element of the learning process. Feedback connects assessment, instruction, and learning, helping students develop a deeper understanding of the subject matter. The effective use of feedback can also significantly contribute to teachers’ professional knowledge and expertise, representing a core component of their assessment literacy. It is also crucial to persist in shifting the traditional perception of assessment, moving away from a purely summative perspective. Assessment should not be understood solely as a measure of success, but rather as an integral part of the learning process, serving to enhance instruction and support student development. Achieving these goals requires structural changes in education policy, including a shift from high-stakes testing toward ongoing formative assessment, particularly in upper primary grades. Schools should be supported in creating conditions for effective feedback and formative practices. Initial teacher education and professional development must include well-structured modules on the theory and practical application of formative assessment. In conclusion, the results highlight the need for further support for teachers in developing formative assessment practices, as well as for broader structural changes that would reduce the pressure of high-stakes examinations and strengthen assessment focused on the learning process.

Recommendations

The findings of this study have important implications for educational practice. The observed differences in assessment conceptions between lower and upper primary teachers highlight the need for targeted professional development programs. These programs should be tailored to the specific needs of each group, considering their academic qualifications, teaching experience, professional title, and subject area, particularly regarding upper primary teachers (grades 5–8). Special attention should be given to the development of teachers’ competencies in formative assessment, specifically assessment for learning and assessment as learning, with a focus on practical implementation in the classroom. Effective formative assessment implementation requires structured, practice-oriented professional development, focused on quality feedback, rubric design, and concrete classroom strategies. Ongoing support through digital platforms with good practice examples is essential. Training should be tailored to different primary levels, with self-assessment used to monitor professional growth. It is also essential to investigate the underlying causes of the observed differences between lower and upper primary teachers and to design and evaluate professional development programs that provide teachers with the necessary support for applying modern assessment approaches. Furthermore, future research should explore the influence of school context, including school culture and educational policies, on teachers' conceptions and assessment practices.

Limitations

A key limitation of this study is the relatively small sample size and the reliance on self-assessment in the survey process. Future research should include a larger and more representative sample and employ a mixed-method approach that incorporates direct observations of teaching practices. Specifically, classroom observations could provide insights into the actual application of different assessment methods, offering a more objective perspective on teachers' assessment practices. Self-assessment carries the risk of bias, as participants may be influenced by factors such as social desirability, personal beliefs, or the inclination to present themselves in a positive light. These influences can affect the validity of the findings. Participants may have overestimated the frequency and quality of formative assessment due to socially desirable responding, which could lead to overly optimistic conclusions about its implementation in practice. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, self-assessment is inherently subjective, relying on participants' perceptions, making it difficult to verify the accuracy of responses or compare them to objective measures of effectiveness. Additionally, self-assessment may be limited by an individual’s ability to introspect and reflect on their own practices. Despite its limitations, self-assessment can still provide valuable insights into how teachers perceive their own assessment practices and the factors influencing their decision-making. The results obtained through self-assessment can serve as a starting point for further research, incorporating objective methods such as classroom observations, interviews,and document analysis.

Ethics Statements

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Split (KLASA: 029-06/25-03/00002; URBROJ: 2181-190-25-00020)

Generative AI Statement

The authors have not used generative AI or AI-supported technologies.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Letina: conceptualization, design, data analysis and interpretation, statistical analysis, drafting manuscript, analysis, writing. Škugor: conceptualization, data acquisition, critical revision of manuscript, reviewing, final approval. Tomaš: conceptualization, data acquisition, critical revision of manuscript, reviewing, final approval.