Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental condition characterized by persistent deficits in social interaction and communication, alongside restricted and repetitive behaviors. These symptoms typically emerge in early childhood and vary widely in presentation and severity. As ASD affects multiple domains of functioning—including cognitive, emotional, and linguistic development—early diagnosis and intervention are critical for improving long-term outcomes.

Among the most prominent challenges faced by children with ASD are impairments in language acquisition, particularly in lexical (vocabulary-related) and semantic (meaning-related) aspects of speech. While substantial research has explored the linguistic difficulties of children with autism, much of this work has focused on school-aged populations or those with high-functioning autism. Studies specifically examining preschool-aged children with ASD, especially those with moderate to severe symptoms, remain limited. Furthermore, existing interventions often lack detailed attention to the structured development of lexical and semantic language skills during early childhood.

To address this gap, the current study investigates the use of an adapted Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) therapy program adapted to the lexical and semantic needs of preschoolers with ASD. Unlike previous studies, this research focuses on a younger cohort (ages 3–6) and applies a targeted ABA framework to improve vocabulary acquisition, word categorization, and contextual language use. By combining diagnostic assessment with individualized behavioral intervention, this study contributes novel insights into how structured early intervention can effectively enhance the language development of children with ASD who are often underrepresented in the literature.

Children with ASD often display social withdrawal, atypical responses to sensory input, and limited engagement with their surroundings. These behaviors contribute to communication difficulties and slow developmental progress, especially in language acquisition (Ersarina et al., 2020; Zhunusova et al., 2020). The tendency toward passivity and hypersensitivity further complicates their interaction with the environment, making early intervention essential.

These children also struggle with changes in routine, which can trigger emotional distress and behavioral outbursts. Minor disruptions—such as changes in objects, feeding times, or daily transitions—can cause agitation and resistance (Campisi et al., 2018; Hyman et al., 2020). This highlights the need for structured, consistent environments that support learning and reduce barriers to communication development.

Language development plays a crucial role in assessing the overall progress of children with ASD. Receptive and expressive vocabulary skills are widely recognized as reliable indicators of cognitive and communicative functioning (Blume et al., 2021; Hodges et al., 2020). These markers provide valuable insights into the child’s developmental trajectory and inform appropriate intervention strategies.

Among the core challenges in ASD is a significant deficit in functional communication. Delayed or absent speech, limited initiation of conversation, and reliance on stereotyped language often prevent meaningful social integration. Addressing these issues through adapted interventions is vital for improving both communication outcomes and broader developmental success.

Importantly, research suggests that the root of language difficulties in children with ASD lies more in lexical and semantic processing than in phonetics or syntax. That is, these children often struggle with understanding word meanings and semantic relationships (Luyster et al., 2008; Tager-Flusberg & Kasari, 2013). Semantic challenges may include difficulties with categorization, word retrieval, and contextual usage, often varying with the severity of ASD and the child’s cognitive profile. Supporting this, Mercado et al. (2020) note that “children with ASD may learn categories differently because they process sensory patterns in ways that are more strongly shaped by their unique, experience-dependent developmental histories” (p. 696). This altered perceptual and cognitive processing can significantly impact how lexical and semantic information is acquired and organized.

ABA therapy provides a structured approach to addressing lexical and semantic deficits. ABA focuses on the systematic development of socially significant behaviors, including communication and language skills, through the use of reinforcement and measurable behavioral goals. It is widely supported as an effective intervention for children with developmental disorders, including ASD.

From a behavioral perspective, language is a learned skill that can be shaped through evidence-based interventions. Prior studies have shown that ABA techniques—when individualized and applied consistently—can significantly enhance speech and language acquisition in children with ASD (Autaeva & Bekmurat, 2023; Roane et al., 2016). These findings reinforce the importance of ABA-based methods in promoting meaningful communication improvements during early development.

While previous studies have explored lexical and semantic development in children with autism, most have focused on school-aged children or those with high-functioning profiles. Very few have specifically targeted preschool-aged children (ages 3–6), despite this being a critical period for language acquisition. Furthermore, there is a notable lack of research using validated diagnostic tools in the Kazakh or Russian languages to measure changes in lexical and semantic speech development. This linguistic and cultural gap limits the generalizability of findings to local contexts. The present study addresses this gap by focusing on preschoolers with ASD and employing a validated, culturally appropriate assessment tool in Kazakh and Russian.

Research Objective: To develop and scientifically substantiate an adapted ABA therapy program for enhancing the lexical and semantic aspects of speech in children with autism aged 3 to 6 years.

Research Questions:

What are the lexical and semantic characteristics of speech in preschool children with autism aged 3 to 6 years?

How effective is an adapted ABA therapy program in developing the lexical and semantic aspects of speech in these children?

Does the implementation of the adapted ABA therapy lead to measurable improvements in the communicative function of speech in preschool children with autism?

Literature Review

Lexical and Semantic Deficits in Children with ASD

Children with ASD often exhibit atypical development in lexical and semantic domains, which are foundational for functional communication. While some studies suggest pervasive difficulties in these areas, others report preserved or near-typical development, underscoring the heterogeneity of ASD(Sukenik & Tuller, 2023). For instance, Politis et al. (2023) found that some children with ASD struggle to categorize word meanings—a skill that typically developing peers acquire more readily—suggesting fundamental deficits in semantic organization. In contrast, Gladfelter and Barron (2020) demonstrated that high-functioning children with ASD categorized semantically related words similarly to neurotypical peers. This divergence highlights that while semantic processing is often impaired, it may remain intact for some individuals depending on cognitive and developmental factors.

Further complexity is introduced by Bernstein and Tiegerman-Farber (2009), who noted that children with ASD often rely on atypical memory strategies, such as recalling words based on phonetic similarity or superficial semantic links. For example, children might say “nail” instead of “pin,” or “bird” instead of “chicken.” In contrast, neurotypical children interpret unfamiliar words by describing function or use. These findings suggest that even when vocabulary knowledge exists, the underlying processing strategies differ substantially in ASD.

Adding nuance, Barone et al. (2019) found no significant differences between children with ASD and their neurotypical peers in vocabulary knowledge across eleven semantic categories (animals, vehicles, toys, food and drinks, clothing, body parts, furniture and rooms, household items, miscellaneous objects, people, and actions). Interestingly, children with ASD in this study demonstrated vocabulary growth consistent with typical developmental trajectories. Taken together, these studies illustrate the variable lexical-semantic profile in ASD, emphasizing the need for interventions tailored to individual strengths and deficits.

Assessment of Lexical and Semantic Language in ASD

Accurately assessing the lexical and semantic abilities of children with ASD is both crucial and challenging due to the diversity of language profiles and behavioral presentation. Standardized tools such as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) and the Mullen Scales of Early Learning have revealed consistent receptive language delays in children with ASD (Kover et al., 2013; Riley et al., 2019). Similarly, Landa and Garrett-Mayer (2006) found that children with ASD performed significantly lower on spoken language assessments compared to children with non-specific language delays. However, traditional tools may underestimate capabilities due to behavioral or attentional difficulties inherent in ASD, indicating the importance of alternative or adapted assessment methods.

One such tool is the Word Finding Vocabulary Test (WFVT), which assesses both recognition and expressive labeling of images from familiar contexts. Vogindroukas et al. (2003) showed that while children with ASD could often describe partial images in detail, they had difficulty retrieving the correct lexical item when viewing the whole image. This disconnect suggests that lexical access, rather than semantic understanding alone, may be a limiting factor.

Although studies using electroencephalography (EEG) and event-related potentials (ERPs) such as the N400 component have provided neurophysiological insights into semantic processing in ASD (Ahtam et al., 2020; DiStefano et al., 2019; Fishman et al., 2011; Friedrich & Friederici, 2010), such techniques were not employed in the present study due to practical constraints in working with preschool-aged children. Nevertheless, prior ERP findings do inform the understanding that semantic processing anomalies in ASD can arise from underlying neural mechanisms, which reinforces the need for behavioral interventions that support language acquisition.

ABA-Based Interventions and Language Development in ASD

ABA is widely recognized as a scientifically grounded approach for addressing developmental challenges in children with ASD, including language delays. Rooted in learning theory, ABA focuses on reinforcing desired behaviors and minimizing maladaptive ones. Pioneering work by Lovaas (1987) demonstrated that intensive ABA-based interventions could produce substantial cognitive and language gains, with nearly half of participating children achieving developmental parity with their typically developing peers.

Subsequent studies have confirmed ABA’s utility in supporting both foundational and complex verbal behaviors. For instance, Sundberg and Michael (2001) and Smith et al. (2015) demonstrated that ABA-based protocols, particularly those incorporating verbal behavior frameworks, effectively promote language acquisition in children with developmental disabilities. Pyles et al. (2021) similarly found positive outcomes in speech and language development following ABA interventions.

However, ABA has not been universally embraced. Critics argue that traditional ABA may overly emphasize compliance, foster dependence on prompts, and fail to respect the individuality of autistic learners (Saar et al., 2023; Sandoval-Norton et al., 2019; Shkedy et al., 2021). These concerns have prompted calls for more flexible and ethical adaptations of ABA that integrate naturalistic teaching, promote autonomy, and prioritize meaningful communication over rote responses.

In response to these criticisms, the present study implemented an adapted ABA protocol that retains core behavioral principles while incorporating developmentally appropriate practices such as visual supports, functional communication training, and preference-based reinforcement. This approach aims to balance structured teaching with individualized engagement, thereby addressing both the linguistic deficits and ethical considerations raised in recent discourse.

Bridging to the Current Study

While prior research has documented both the potential and limitations of ABA in language development, few studies have focused specifically on its application to lexical and semantic development in preschool-aged children with ASD. Furthermore, limited attention has been given to integrating individualized, critique-informed adaptations into ABA frameworks. The present study addresses this gap by evaluating the impact of an adapted ABA intervention targeting lexical-semantic deficits using validated behavioral assessments. By focusing on discrete trial teaching, visual supports, and contextually meaningful vocabulary tasks, this study aims to contribute evidence on how ABA can be ethically and effectively refined to support early language development in ASD.

Methodology

Research Design

This study employed a quasi-experimental, pretest–posttest nonequivalent-groups design to evaluate the effectiveness of Adapted ABA therapy in enhancing the lexical and semantic development of preschool-aged children with ASD. While initially referred to as a "diagnostic experiment," the actual design involved baseline measurement, intervention, and post-intervention assessment in both control and experimental groups. Random assignment was not feasible due to the fixed enrollment of participants in each center. Instead, efforts were made to minimize selection bias by ensuring both groups were equivalent at baseline through independent samples t-testing and by maintaining comparable age ranges, language backgrounds, and developmental profiles.

Participants and Sampling

A total of 60 children aged 3 to 6 years, all diagnosed with ASD, were selected from two rehabilitation centers in Kazakhstan: The Autism Support Center in Kyzylorda (control group, n = 30) and the "RostOK" Rehabilitation Center in Almaty (experimental group, n = 30). The inclusion criteria were: formal ASD diagnosis by a psychological-medical-pedagogical commission, age between 3 and 6 years, and no co-occurring neurological disorders. Stratification by age and language background (Kazakh- vs. Russian-speaking) was implemented to ensure group comparability (Table 1, and 2).

Table 1. Age Range of Children at the Autism Support Center in Kyzylorda

| Age | Exact Age of Children (Years, Months) | Average age range | Total number |

| 3 years old | 3, 3; 3, 8 | 3, 5 | 2 |

| 4 years old | 4, 1; 4, 2; 4, 4(2); 4, 5(3); 4, 6; 4, 7(2); 4, 8; 4, 10(3) | 4, 4 | 14 |

| 5 years old | 5, 4(3); 5, 7(2); 5, 10(2); 5, 11 | 5, 3 | 8 |

| 6 years old | 6, 2(2); 6, 4; 6, 7; 6, 9(2) | 6, 5 | 6 |

| Total | 30 |

At the Autism Support Center in Kyzylorda, among the 30 children, 27 were boys and 3 were girls. Additionally, 27 children were Kazakh-speaking, while 3 were Russian-speaking. The age range of the children in the control group was from 3 years and 3 months to 6 years and 9 months.

Table 2. Age Range of Children at the 'RostOK' Rehabilitation Center in Almaty

| Age | Exact Age of Children (Years, Months) | Average age range | Total number |

| 3 years old | 3, 2; 3, 3; 3, 10(2) | 3, 1 | 4 |

| 4 years old | 4, 3(2); 4, 4; 4, 5; 4, 7(2); 4, 10(3) | 4, 3 | 9 |

| 5 years old | 5, 1; 5, 2; 5, 3; 5, 4(2); 5, 5(2); 5, 7(2); 5, 8; 5, 9; 5, 10 | 5, 4 | 12 |

| 6 years old | 6; 6, 3; 6, 4; 6, 7; 6, 11 | 6, 3 | 5 |

| Total | 30 |

At the 'RostOK' Rehabilitation Center in Almaty, the number of participants was 30, all diagnosed with ASD. Among them, 25 were boys and 5 were girls. Additionally, 22 children were Kazakh-speaking, while 8 were Russian-speaking. The age range of the participants was from 3 years and 2 months to 6 years and 11 months

The sample size of 60 was informed by prior research on behavioral interventions in children with ASD (Peters-Scheffer et al., 2011). A priori power analysis using G*Power (version 3.1) indicated that a sample of 54 would be sufficient to detect a medium effect (d = 0.6) with 80% power at α = .05. Thus, a final sample of 60 was chosen to maintain statistical power while accounting for potential attrition.

Assessment Tool

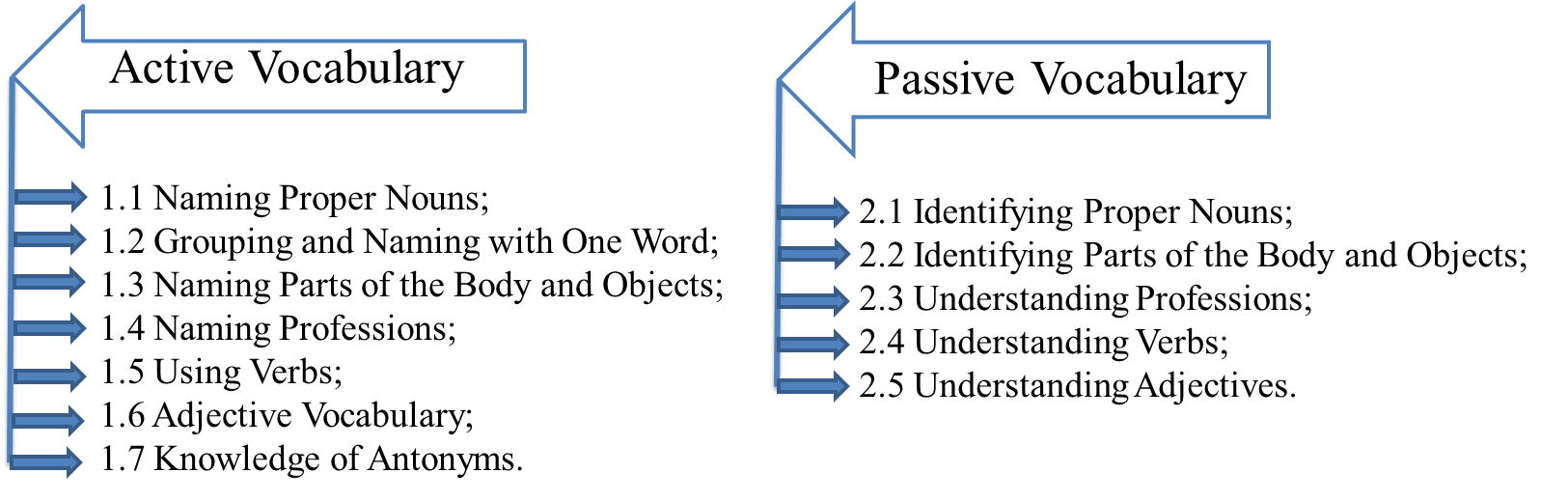

Lexical and semantic abilities were assessed using the Methodology for Assessing the Volume and Quality of Lexicon and Semantics (Serebryakova & Solomakhova, in Balobanova et al., 2000), a diagnostic protocol evaluating active vocabulary (naming, grouping, word classes) and passive vocabulary (object recognition, verb and adjective comprehension). The instrument includes 13 subtests, producing a cumulative score ranging from 0 to 160, with interpretive bands: high (108–160), medium (54–107), and low (0–53).

To streamline the presentation, the full scoring rubric is presented in Appendix. Figure 1 summarizes the structure of the assessment tool.

Figure 1. Assessing the Volume and Quality of Lexicon and Semantics

Reliability and Validity

Internal consistency for the scale was measured using Cronbach’s α in our sample, yielding α = 0.91, indicating excellent reliability. Inter-rater reliability was assessed in 20% of sessions using independent coders and Cohen’s κ = 0.88, reflecting strong agreement. The instrument’s construct validity and clinical utility have been previously supported in Russian-language populations with developmental delays (Balobanova et al., 2000).

Intervention Procedure

The adapted ABA therapy program was implemented over the course of 9 months, corresponding to one full academic year (September to May). This extended duration allowed for a more sustained and comprehensive intervention targeting the lexical and semantic development of children with ASD.

Each child in the experimental group received:

5 sessions per week

4 hours per session

Total dosage: approximately 720 hours over the academic year

Sessions were delivered in both one-on-one and small group formats, depending on the individual needs of the child. Each session followed a structured plan grounded in ABA principles, incorporating discrete trial training (DTT), visual supports, functional communication training, differential reinforcement strategies, and techniques for generalization. Instructional content focused on enhancing vocabulary, word categorization, naming, and the appropriate contextual use of language.

Therapist Qualifications and Fidelity

All intervention sessions were administered by certified special educators with a minimum of two years of experience in implementing ABA-based therapies for children with developmental disorders. Prior to the start of the program, all therapists completed a 10-hour refresher course specifically focused on the adapted protocol used in this study. The course incorporated modules from regionally approved ABA training frameworks, emphasizing language development, discrete trial teaching, and individualized instructional strategies. To ensure fidelity of implementation, supervisors conducted structured observations during 25% of all sessions using a standardized 10-item checklist. Fidelity scores averaged 93%, indicating a high level of adherence to intervention procedures and confirming procedural reliability across therapists.

The study adhered to the ethical standards outlined by the Republic of Kazakhstan, ensuring the protection of participants' rights throughout the research process. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participants, ensuring they were fully aware of the study's purpose, procedures, and potential risks. Confidentiality was maintained rigorously, with all data anonymized to prevent any identification of individual participants. Ethical oversight was provided to guarantee that the study adhered to all relevant regulations and guidelines.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (v26). The following steps were performed:

Normality of pre- and post-test scores was tested using Shapiro–Wilk tests (p > .05 for both groups), confirming normality.

Homogeneity of variances was assessed using Levene’s test (p > .05), satisfying assumptions for t-tests.

Within-group changes were evaluated using paired-samples t-tests.

Between-group differences were examined using independent samples t-tests.

Cohen’s d was calculated to determine effect size.

To control for baseline differences and improve precision, an ANCOVA was performed with post-test scores as the dependent variable and pre-test scores as a covariate.

Findings/Results

Pre-Intervention Group Comparison

Before assigning participants to control and experimental groups, an independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the lexical-semantic scores of children from the Autism Support Center and the "RostOK" Rehabilitation Center. Table 3 provides descriptive statistics and group comparison results.

Table 3. Pre-Intervention Group Comparison Using Independent Samples t-Test

| Group | N | Mean Score | SD | SE Mean |

| Autism Support Center | 30 | 64.3 | 29.6 | 5.4 |

| RostOK Center | 30 | 60.8 | 29.2 | 5.3 |

| Test Statistic | Value | 95% CI for Mean Difference | p-value | |

| t | .47 | (-11.66, 18.72) | .643 |

No statistically significant difference was found (p = .643), confirming baseline equivalence across groups. Based on logistical feasibility and center preferences, the Autism Support Center was assigned as the control group and the RostOK center as the experimental group.

Descriptive Statistics: Pre- and Post-Test

Table 4 summarizes the lexical-semantic development scores (mean ± SD) before and after the intervention for both groups.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for Pre- and Post-Intervention Scores

| Group | Time Point | Mean Score | SD |

| Control Group | Pre-Test | 64.3 | 29.6 |

| Control Group | Post-Test | 84.2 | 28.4 |

| Experimental Group | Pre-Test | 60.8 | 29.2 |

| Experimental Group | Post-Test | 115.6 | 26.1 |

These values show a substantial increase in scores post-intervention, particularly in the experimental group.

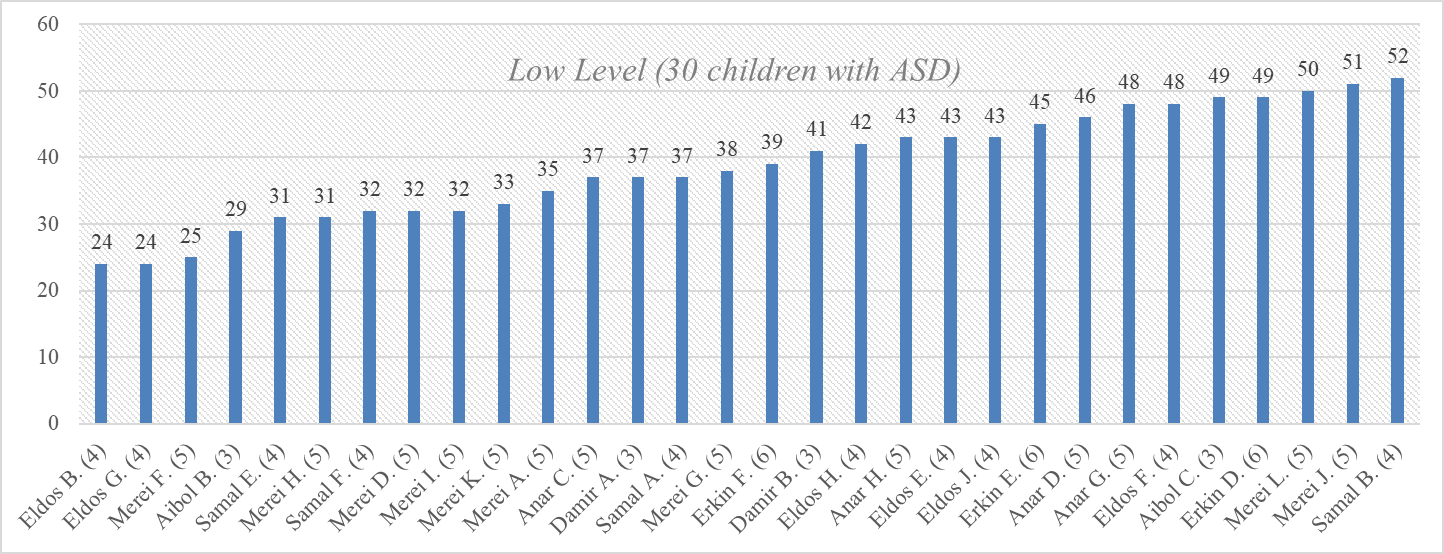

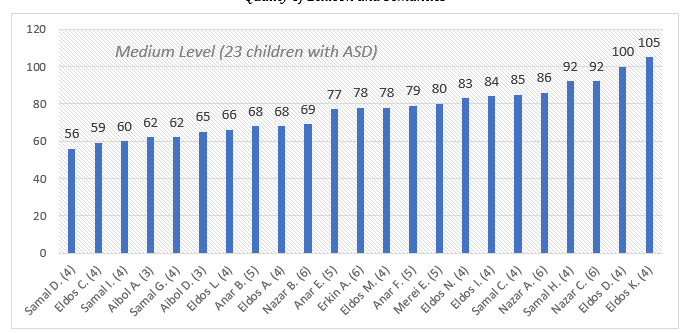

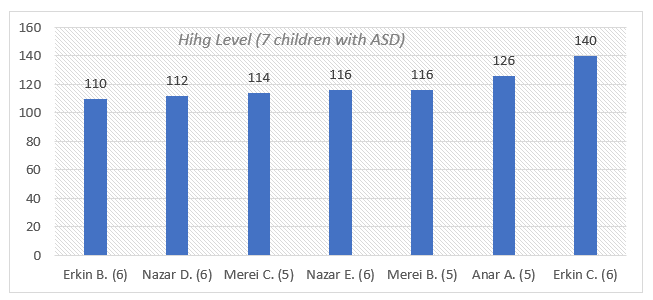

Figure 2, 3, 4 illustrate the number of children who scored in low, medium, and high bands at baseline based on the assessment tool.Levels determined using validated scoring bands: Low (0–53), Medium (54–107), High (108–160).

Figure 2. Indicator of Low Level in Children with Autism Based on the Methodology for Assessing the Volume and Quality of Lexicon and Semantics

Figure 3. Indicator of Medium Level in Children with Autism Based on the Methodology for Assessing the Volume and Quality of Lexicon and Semantics

Figure 4. Indicator of High Level in Children with Autism Based on the Methodology for Assessing the Volume and Quality of Lexicon and Semantics

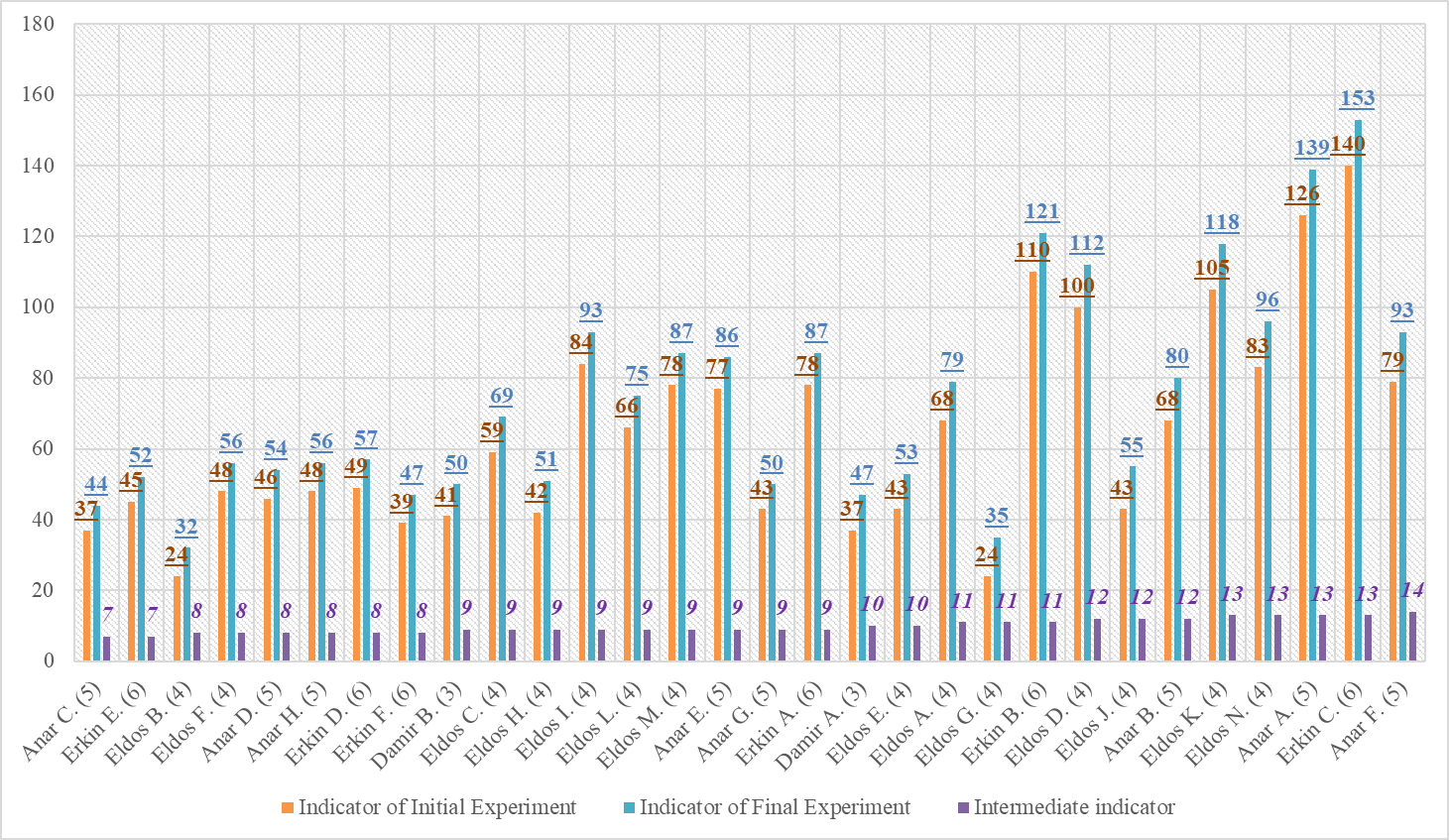

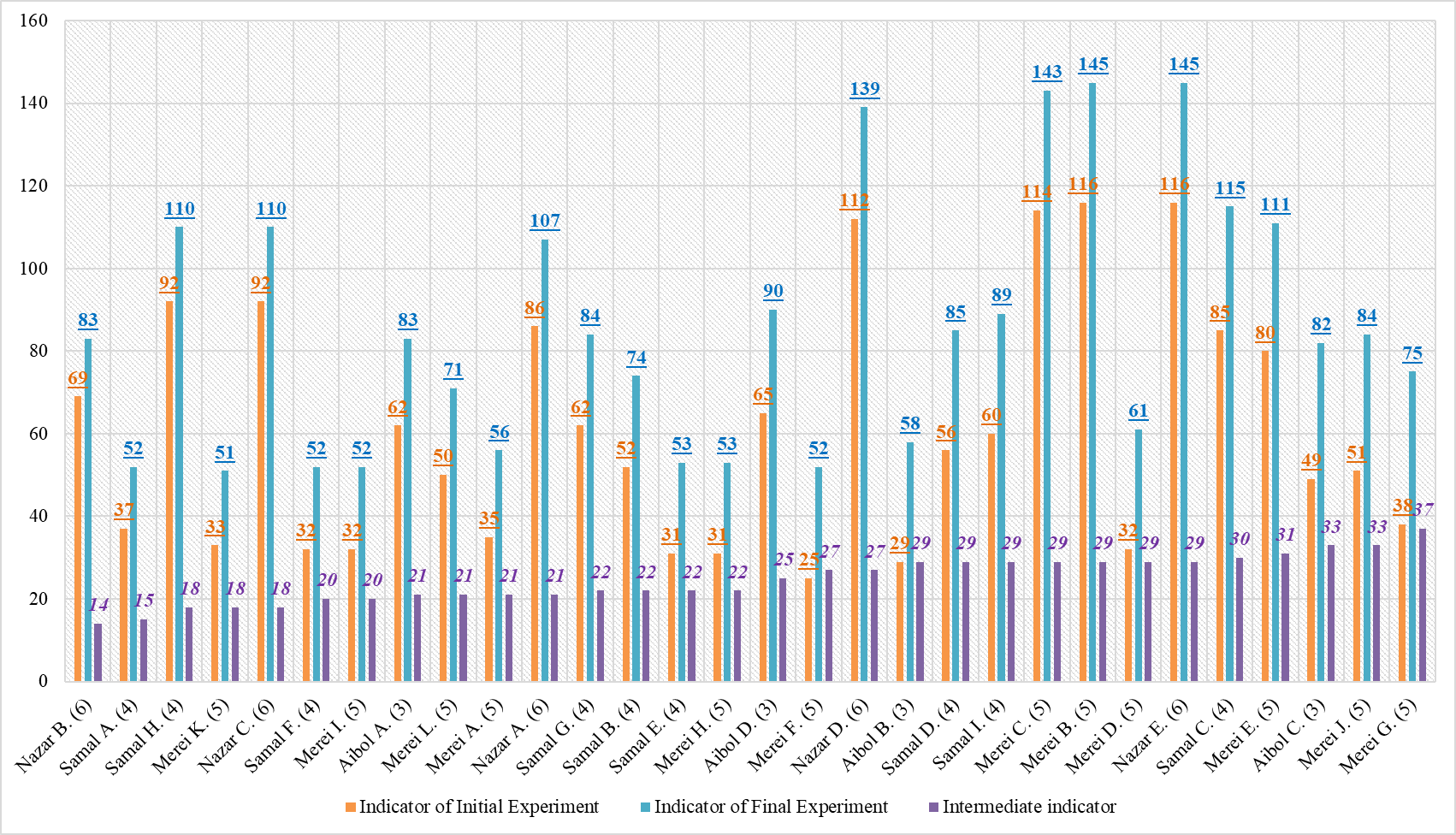

Figures 5 and 6 illustrate the pre- and post-test score distributions in the control and experimental groups, respectively.

Figure 5. Pre- vs. Post-Intervention Score Changes in the Control Group

The histogram shows average score improvement for the control group. Some gains were observed without specific lexical-semantic programming.

Figure 6. Pre- vs. Post-Intervention Score Changes in the Experimental Group

The histogram illustrates a larger score shift in the experimental group, reflecting targeted intervention impact.

ANCOVA Results

An analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was conducted to evaluate the effect of the adapted ABA intervention on post-test scores, using pre-test scores as a covariate to control for baseline differences. The results revealed a statistically significant difference between groups on post-intervention scores after adjusting for pre-intervention performance.

The ANCOVA demonstrated that the adapted ABA intervention had a significant and independent effect on children’s lexical-semantic development, F(1, 57) = 16.87, p < .001, with a large effect size (partial η² = .23). The covariate (pre-test scores) was also a significant predictor, F(1, 57) = 32.74, p < .001, partial η² = .37.

This indicates that the adapted ABA intervention had a strong, independent effect on post-test outcomes after adjusting for pre-test scores.

Summary of Key Findings

Baseline comparisons confirmed no significant differences between the control and experimental groups in lexical-semantic skills prior to the intervention. Following the adapted ABA program, both groups showed statistically significant improvements; however, the experimental group demonstrated substantially greater gains. Effect size analysis revealed a large effect (Cohen’s d = 1.55) in the experimental group compared to a moderate effect (Cohen’s d = 0.75) in the control group. ANCOVA further validated the intervention's impact, showing that post-test differences remained significant after adjusting for baseline scores. These findings support the effectiveness of the adapted ABA intervention in improving lexical and semantic development in preschool-aged children with ASD.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that an adapted ABA intervention significantly improved the lexical and semantic language skills of preschool-aged children with ASD over a nine-month period. These results are consistent with prior findings supporting the efficacy of behavioral interventions in promoting verbal development. The large effect size observed in the experimental group suggests that the adapted ABA components – such as discrete-trial repetition, functional communication strategies, and structured visual support – played a substantial role in facilitating lexical retrieval and semantic organization.

This study adds to the growing body of evidence supporting individualized, language-focused adaptations of ABA therapy. Repeated exposure through discrete trials likely strengthened lexical associations and retrieval fluency, while visual prompts and reinforcement strategies may have supported both word recognition and semantic categorization. By explicitly targeting lexical-semantic domains—rather than broad linguistic functioning—the intervention more precisely addressed the communicative deficits most commonly observed in children with ASD.

These outcomes are consistent with the view that the development of lexical and semantic systems is a gradual and multifactorial process. Researchers such as Ellis Weismer and Kover (2015), Rescorla and Safyer (2013) have emphasized that children with ASD often exhibit atypical language trajectories characterized by slower vocabulary growth, challenges in semantic organization, and limited generalization of word knowledge. Language acquisition in this population is influenced by a range of factors, including the enrichment of sensory experiences, increased interaction with the environment, cognitive development, and engagement in object-based and symbolic play.

Empirical studies (Arunachalam & Luyster, 2018; Bekmurat et al., 2024; Gladfelter & Goffman, 2018) have documented distinctive quantitative and qualitative features of lexical-semantic development in children with ASD. These include difficulties in vocabulary use, word substitutions, prolonged and non-automated word retrieval, incomplete semantic field formation, random associations, verbal paraphasia, and misuse of lexical opposites such as synonyms and antonyms. The structured, repetitive, and visually supported nature of the adapted ABA intervention used in the current study may have mitigated several of these difficulties by providing consistent retrieval practice and scaffolding semantic connections in a developmentally appropriate manner.

However, it is important to situate these results within the broader, sometimes inconsistent literature. For example, Haebig et al. (2015) and Yu et al. (2020) reported less robust or slower vocabulary gains in children with ASD following early intervention. One reason for this discrepancy may lie in methodological differences: their interventions were not ABA-based or did not use focused lexical-semantic tasks, instead emphasizing broader social or syntactic development. In contrast, our program provided frequent, highly structured, and semantically grounded practice, which may better support initial vocabulary acquisition. Additionally, our sample received intensive therapy (4 hours/day, 5 days/week), whereas the intensity in some prior studies was lower.

Despite the promising results, generalization of learned language to natural contexts remained a challenge, echoing concerns from previous studies. Although improvements were evident within therapy settings, spontaneous use of new vocabulary across environments was more limited. This suggests that while adapted ABA can promote lexical-semantic acquisition, further strategies are needed to support generalization. Future adaptations should consider embedding language practice in more naturalistic or peer-based activities to encourage carryover beyond structured sessions.

Moreover, these findings should not be generalized beyond the specific population studied. All participants were preschool-aged Kazakh and Russian-speaking children enrolled in specialized rehabilitation centers. The structured, center-based environment and high therapist-to-child ratio may not reflect broader community or inclusive educational settings. Therefore, claims about the universal applicability of adapted ABA must be made cautiously. Replication with more diverse samples, settings, and languages is needed.

In summary, this study supports the efficacy of adapted ABA in promoting lexical-semantic growth in children with ASD, particularly when interventions are intensive, individualized, and semantically focused. However, limitations in generalization, sample diversity, and conflicting findings in the literature call for ongoing refinement of therapy design and expanded research.

Conclusion

The findings of this study provide strong support for the use of an adapted ABA intervention in fostering lexical and semantic language development in preschool-aged children with ASD. Unlike standard ABA protocols that often focus broadly on behavior management or general language acquisition, the adapted model employed here emphasized individualized instruction in specific lexical-semantic domains. It incorporated discrete-trial repetition, visual supports, and functional communication strategies—elements carefully selected to align with the unique linguistic and cognitive profiles of children with ASD.

The necessity of this adaptation stems from both clinical observation and research literature indicating that many children with ASD struggle not with lexical memory, but with challenges in word classification, contextual application, and semantic comprehension. While expressive language development in ASD is highly variable, approximately 25–30% of children remain minimally verbal, relying on single words or formulaic phrases for interaction (Pickles et al., 2014; Sibuea et al., 2024). Even with early intervention, speech impairments frequently persist. Semantic difficulties—including delayed word retrieval, incomplete semantic field formation, and inappropriate word substitutions—are well documented and vary depending on both autism severity and cognitive ability (Zarokanellou et al., 2024).

By directly addressing these lexical-semantic challenges, the adapted ABA protocol used in this study produced meaningful gains in vocabulary acquisition and semantic organization. These improvements likely result from the structured repetition of discrete trials, which provide children with repeated opportunities for lexical retrieval, supported by consistent reinforcement and multimodal cues. The intervention’s success further confirms the broader body of evidence supporting the long-term efficacy of ABA-based strategies (Choi et al., 2022; Du et al., 2024), while demonstrating that strategic modification can optimize language outcomes in populations with complex developmental profiles.

From a practical standpoint, these findings advocate for the integration of adapted ABA strategies into early intervention frameworks specifically targeting language development. Educational and clinical professionals should be encouraged to adapted ABA-based instruction not only to general behavioral goals but also to the nuanced semantic and expressive needs of children with ASD. At the policy level, these results point to the need for expanding access to specialized training for therapists and the development of culturally and linguistically responsive intervention tools.

Future research should examine the long-term impacts of adapted ABA on functional communication and vocabulary generalization beyond the therapy setting. Additionally, comparative trials across traditional and adapted ABA approaches in varied linguistic, cultural, and service delivery contexts will be critical to defining best practices and ensuring equitable application of evidence-based interventions across populations.

Recommendations

Given the inherent variability of ASD, it is essential to recognize that no two children with ASD develop in the same way. Intervention strategies must be highly individualized, ensuring that each child receives support tailored to their unique abilities, challenges, and strengths.

Educational and therapeutic interventions should be adapted based on the child's specific cognitive and linguistic capabilities, ensuring meaningful progress in lexical-semantic development. ASD interventions should continuously evolve by incorporating the latest findings in education, psychology, and neuroscience, allowing for evidence-based adaptations that enhance language acquisition outcomes.

The successful implementation of ASD interventions depends on the competency and expertise of professionals. It is essential to develop comprehensive training programs that equip specialists with the necessary skills to deliver high-quality, individualized interventions. Given that ASD-related interventions are pedagogical in nature (Barton & Smith, 2015; Hume et al., 2021; Odom et al., 2021), educational frameworks should be continuously updated and refined to align with the evolving needs of children with ASD, ensuring that teaching methodologies remain effective and research-driven.

A holistic approach to intervention requires active coordination and communication among teachers, speech therapists, behavioral analysts, and parents. This ensures consistency in learning strategies and reinforces progress in multiple environments. By implementing these approaches, intervention efforts can be more effective, sustainable, and responsive to the diverse needs of children with ASD, ultimately enhancing their linguistic, cognitive, and communicative competencies.

Limitations

Despite the well-documented benefits of adapted ABA therapy, several critical limitations must be considered. While substantial advancements in lexical and semantic development were evident, the extent of progress exhibited considerable heterogeneity across individuals, underscoring the necessity for long-term, highly individualized intervention frameworks that accommodate the diverse cognitive and linguistic profiles of children with ASD. Furthermore, the transferability and generalization of acquired skills across varied communicative and social contexts remained a persistent challenge, necessitating continuous reinforcement strategies and structured, multi-environmental support systems to ensure sustained developmental gains.

The efficacy of ABA therapy is also inherently contingent upon a range of extrinsic variables, including the availability and expertise of trained professionals, the level of parental engagement, and the consistency of intervention implementation. Additionally, the heterogeneous symptomatology of ASD, coupled with variability in cognitive capacities, significantly modulates therapeutic outcomes, necessitating further empirical investigation into differential response patterns and optimization strategies for distinct subgroups within the ASD population.

Ethics Statements

The scientific and practical work was conducted in accordance with the ethical requirements of the legislative foundations of the Republic of Kazakhstan, including the Law on Education and the Law on the Rights of the Child. Permission was obtained from the institution's administrators and the children's parents or legal guardians for the research. The names of the children have been changed.

The author would like to thank the administration of the research institution and the dedicated teachers working with children with ASD for their invaluable contributions, commitment, and collaboration in facilitating this study. Lastly, profound gratitude is expressed to all the children with ASD and their families, whose participation and cooperation were instrumental in the completion of this study.

Conflict of Interest

No discrepancies or misunderstandings arose among teachers, parents, or other stakeholders within the research setting throughout the study's implementation and the subsequent preparation of this article.

Funding

This research is funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (Grant No. BR28712661 – National system for comprehensive continuous support of students with autism spectrum disorder)

Generative AI Statement

As the authors of this work, we used the AI tool [Chat GPT] for the purpose of [translation and improving fluency]. After using this AI tool, we reviewed and verified the final version of our work. We, as the authors, take full responsibility for the content of our published work.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Bekmurat: Conceptualization, design, analysis, writing. Autayeva: Editing/reviewing, supervision.