Introduction

Critical reading is a skill most individuals require even when juggling so much information today. This does not just involve comprehension but also includes the exanimation, assessment, and filtering of the information provided(Sriwantaneeyakul, 2018).The required critical thinking skill is developed based on this skill, which enables students to engage actively and energetically with information. Engaging with information entails interpretation, questioning, and argument formulation based on what was received(Bobkina & Stefanova, 2016).Still, research shows that a significant number of students have difficulties fostering practical critical reading skills (Ratanaruamkarn et al., 2023). Such a case stems from an educational perspective which relies heavily on context devoid of a critical approach to assessing the student's understanding of the ability to analyze, evaluate, and try to synthesize (Atmazaki et al., 2019). Such an approach is beneficial in tackling the limitations of the reading teacher's pedagogy, which focuses on the development of reading and even memorization at the expense of critical thinking (Quanqin & Cheong, 2023). This results in a lack of comprehension-based discourse and decision-making, which in most cases is shallow. All these professionals and academicians need to be competent with these skills and knowledge (Varaporn & Sitthitikul, 2019).

From a scholarly perspective, the accurate interpretation of reading texts has been a problem for quite some time. In this model, students are advised to work in groups to share their opinions and discuss and analyze the provided reading text, its arguments, and its key ideas (Quanqin & Cheong, 2023). It is well known that cooperative learning improves critical thinking since the students are no longer passive learners; they actively engage in analyzing and evaluating information (Atmazaki et al., 2019). Students are also instructed to learn ways of looking at a given issue from different angles. As well they know how to collaboratively design solutions to problems (Zhang & Wang, 2024). However, the main challenge of this model is that, even with the large number of studies validating this model, there is still a problem of inequality in the use of educational resources across different regions and levels of education (Zhou et al., 2019). This inequality can be in the form of differences in access to teaching materials, technology, and supporting facilities that significantly affect the implementation of optimallearning models (Qaribilla et al., 2024; Zhao, 2024). In many areas, mainly rural or remote areas, limited resources can hinder educators' ability to effectively implement cooperative models, impacting students' critical reading skills (Dong et al., 2022). Therefore, while this model has proven effective in specific contexts, addressing these inequalities is essential in ensuring that all students, regardless of their location or socio-economic status, can benefit from this approach (Dong et al., 2022).

Despite the great promise collaborative learning models hold for improving critical reading skills, many challenges obstruct their practice. As this model has been tested in many research studies, it appears that not all teachers have been adequately trained to employ these strategies (B. Wang et al., 2022). In addition, the practice of cooperative learning is constrained by two factors: inadequate resources and insufficient time (Heo et al., 2014). A great need is to assess this model’s effectiveness across different educational contexts thoroughly. Such assessment can be done through meta-analysis designs that seek to establish the determinants of successful cooperative learning. These determinants are the classroom practices employed, the level of teacher preparedness, and the available classroom and curriculum resources. The results of this meta-analysis study are expected to provide, at best, a deeper understanding and practical suggestions to increase the cooperative learning model's effectiveness in teaching critical reading skills at all education levels.

Even with the implementation of various theories and models intended for improving critical reading skills, research suggests that much remains unknown regarding the most effective practices. A few learning theories, like self-paced or experiential learning, tend to be deficient in providing learners with a socially interactive and collaborative context. For instance, a model that prioritizes personalization or teacher-centred instruction does not always sufficiently encourage students to evaluate and analyse the information given to them actively. Therefore, more effective ways of nurturing critical reading skills in students that enable collaboration must be identified.

This research analyzes the results of scrutinising proficiency understanding of ‘reading’ from 2011-2024.The time range of 2011 to 2024 was chosen for the selection of articles in this study considering that the period reflects the latest developments in applying cooperative learning models in improving critical reading skills. The main focus of this study was to assess the success of cooperative learning models in developing basic reading skills. This model is believed to have great potential in facilitating the development of critical reading skills because of its approach that prioritizes collaboration between students(Ma, 2016). In the cooperative model, students are invited to discuss actively, give each other feedback, and solve problems together, which indirectly improves their ability to analyze and evaluate texts(Hayati et al., 2023). Previous studies using meta-analysis methods have shown that this cooperative-based learning effectively improves reading skills, as it provides more significant opportunities for students to internalize information through social interaction and joint problem-solving. Therefore, the cooperative learning model helps students understand the material and develop critical thinking skills that are essential in reading and processing information.Thus, this study seeks to broaderen our understanding of the effects of cooperative learning models on students’ reading skills and critical thinking indifferent classrooms.

This problem is very relevant because, including other factors, the effective implementation of cooperative learning models requires monitoring critical reading skills to be fully developed and adapted to the needs of students with different cultural and educational backgrounds(Pira & Lisiecka, 2022).Considering critical reading skills' importance to developing one’s ability to think analytically and evaluatively, it is essential to analyse the effectiveness of differentteaching models that promote acquiring these skills. This research aims to provide a solution to how people can counteract these obstacles and coordinate the application for people in authority over the education system. The current studyseeks to find out:

How the cooperative learning model effectively develops learners’ critical reading skills.

The differences between teaching critical reading skills using a cooperative model and teaching critical reading using a cooperative learning model.

Methodology

This study utilised a quantitative method employing a type of meta-analysis. The following steps represent the meta-analytical method asFieldandGillett (2010)Present. The following steps were taken in the course of this study: (a) an existing literature search was conducted, (b) studies were selected for inclusion, (c) the size of the effect was determined, (d) basic meta-analyses were conducted, (e) more complex analyses were conducted to identify moderators and estimate publication bias, and (f) the results were written in article form. The data analysis employed in this study utilised the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V3 (CMA) software, which facilitates the determination of effect size distribution on the forest plot, moderator analysis, and the estimation of publication bias done by the author. The researcher defines the critical reading skills needed as material to select the manuscript to be used in this study. This is because in the selection process using the keywords "critical reading", "critical reading using the koopetarif model", "cooperative model in critical reading" several articles were obtained that substantially did not meet the criteria of "critical reading" by the research theme. The estimated aggregate was calculated as the mean and the difference between groups(Cumming,2012). Therefore, the data utilised in this study are secondary, derived from journal articles published between 2011 and 2024.

A Comprehensive Guide to Literature Search, Identification, and Selection

A comprehensive electronic search was conducted using a variety of databases, including Scopus, Google Scholar, EBSCO, Emerald Insight, Science & Direct, SpringerLink, Taylor & Francis, and ProQuest. This search yielded a total of 489 articles from diverse studies. Subsequently, the study results were selected based on their relevance to teaching critical reading skills using a cooperative learning model. This selection process identified 145 relevant studies. This study aimed to select and focus on research using an experimental/quasi-experimental design, and 48 studies were obtained. The experimental design was chosen using a comparative design of the intervention group and the control group, and 28 studies using experimental designs were obtained from the results of this selection, which is further described in Figure 1.

A search was conducted using an electronic database. The search menu for each journal was utilized. The total number of articles included in the analysis was 489.The following data set contains articles published between 2011 and 2024, with a total of 145 articles included in the analysis.The following exclusions were made:The most recent manuscripts, which were published within the last thirteen years (n = 97), were selected for inclusion.The data set is exclusively comprised of research articles (n = 48).The following exclusions have been made:Non-research articles have been excluded from this analysis (N = 20).The selection process is predicated on the theme of "Critical Reading with a Cooperative Learning Model" (n = 35).The following manuscripts have been excluded from consideration due to their non-alignment with the specified theme, "Critical Reading with the Use of Cooperative Learning Model" (n = 13).A search was conducted to ascertain the abstract and text's compatibility with the prevailing theme (n = 28).The identification of studies is to be conducted via databaseIdentificationnScreeningIncluded

Figure 1.Flow Chart for Meta-Analysis Process by PRISMA Guidelines

In the context of this study, a total of 23 journal articles and five proceedings were utilised as research data sources. The effectiveness of the cooperative learning model in enhancing critical reading skills was assessed by calculating a total of 28 effect sizes. These effect sizes were obtained by comparing the subjects’ pre-test and post-test scores in the experimental group or the experimental and control groups' scores. The meta-analysis also synthesises critical reading scores using a cooperative learning model, drawing from 2043 subjects. The descriptive data of the study and its characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.Data on Independent Variables of the Study

| No | Author and Year | Level | Country | Publication | Sampling Number |

| 1 | Aghaei et al. (2014) | College | Iran | Proceedings | 23 |

| 2 | Aghajani and Gholamrezapour (2019) | College | Iran | Journal | 10 |

| 3 | Akın et al. (2015) | Elementary School | Turkey | Proceedings | 8 |

| 4 | Albeckay (2014) | College | Libya | Proceedings | 13 |

| 5 | Allagui (2021) | College | UEA | Journal | 17 |

| 6 | Ardhian et al. (2020) | Elementary School | Indonesia | Journal | 89 |

| 7 | Asmara et al., (2023) | College | Indonesia | Journal | 95 |

| 8 | Bernal et al. (2023) | Primary High School | Colombia | Journal | 79 |

| 9 | Churat et al. (2022) | Secondary High School | Thailand | Journal | 25 |

| 10 | Darvenkumar and Devi (2022) | College | India | Journal | 56 |

| 11 | Halim (2011) | College | Egypt | Journal | 120 |

| 12 | Hariyati and Ahmadi (2019) | College | Indonesia | Proceedings | 34 |

| 13 | Hazaymeh and Alomery (2022) | College | UEA | Journal | 59 |

| 14 | Hromova et al. (2022) | College | Ukraine | Journal | 138 |

| 15 | Khamkhong (2018) | College | Thailand | Journal | 12 |

| 16 | Khonamri and Karimabadi (2015) | College | Iran | Proceedings | 2 |

| 17 | Koray and Çetinkılıç (2020) | Primary High School | Turkey | Journal | 6 |

| 18 | Lee (2015) | College | Taiwan | Journal | 1 |

| 19 | Lee (2017) | College | Taiwan | Journal | 5 |

| 20 | Mekuria et al. (2024) | College | Ethiopia | Journal | 33 |

| 21 | Moghadam et al. (2021) | College | Iran | Journal | 24 |

| 22 | Mulcare and Shwedel (2017) | College | United States | Journal | 63 |

| 23 | Shalaby (2021) | College | Egypt | Journal | 46 |

| 24 | Shokrpour et al. (2013) | College | Thailand | Journal | 50 |

| 25 | Sultan et al. (2017) | College | Indonesia | Journal | 70 |

| 26 | Varaporn and Sitthitikul (2019) | College | Thailand | Journal | 87 |

| 27 | Yang et al. (2022) | Primary High School | Thailand | Journal | 92 |

| 28 | Yulian (2021) | College | Indonesia | Journal | 126 |

The characteristics of the 28 studies on critical reading using a cooperative model can be analyzed based on the level of essential reading application at the level of education, country, and type of publication. First, in terms of critical reading application levels, most studies focused on primary and secondary education levels. These studies identified that cooperative models are highly effective at increasing students' engagement in reading activities and discussions, which can hone their critical reading skills. At the primary and secondary education levels, skills such as text analysis, questioning information, and composing arguments cooperatively are strengthened through collaboration between students. Meanwhile, studies at the college level show that this model effectively deepens students' understanding of complex academic texts, especially in the context of critical analysis and argument evaluation.

Second, these studies are spread across different countries, with most of the research conducted in countries with advanced education systems, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. These countries have better educational support, so the cooperative model can be implemented more comprehensively with adequate resources. Meanwhile, although there is less research from developing countries, some studies from regions such as Asia and Africa suggest that applying cooperative models in local education can improve students' critical reading skills. However, they often face the challenge of lacking facilities and access to adequate materials. Therefore, although countries with more resources were more dominant in this study, the application of cooperative models in developing countries also showed positive results despite specific barriers.

Third, the types of publications in this study are diverse, ranging from journal articles published in educational journals and educational psychology to conference proceedings and research reports. Published journal articles generally focus on the methods used in research and the results obtained from experiments conducted in various educational settings. Publications in conference proceedings often provide a preliminary view of the effectiveness of cooperative models in more specific countries or regions. In addition, several research reports and dissertations give an in-depth analysis of the impact of this model on critical reading skills, often focusing on teaching techniques and student interaction. This type of publication shows the diversity in the way research is published. It shows that the theme of critical reading with a cooperative model remains a growing and highly relevant area of education research.

Selection Criteria for Included Studies

The criteria for selecting the manuscript used by the researcher to include this study in the meta-analysis are as follows. First, the manuscript must be the result of empirical research relevant to the topic and purpose of this study and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Second, the selected manuscript must present quantitative data that can be extracted for statistical analysis, such as effect size, sample count, and standard deviation or p-value explicitly reported; the complete instrument is as follows.

Table 2. Selection Criteria for the Study Analyzed

| No | Criteria | Study Taken | Eliminated Study |

| 1 | Publication Type | Peer-to-peer review journal article | Journal article publication and peer-to-peer review exchange are integral components of the scholarly communication process. |

| 2 | Year of Publication | The period under consideration extends over thirteen years, commencing in 2011 and concluding in 2024. | Before 2011 |

| 3 | Languages Spoken | English | Languages other than English |

| 4 | Research Design | The following experiments and quasi-experiments utilise control groups and employ critical reading learning models based on cooperative learning models. | Qualitative studiesAction ResearchNon-experimental researchNon-control group experimental research |

Final Selection and Data Extraction

The selected study records were subsequently extracted with data to address the previously posed inquiries. The extracted data comprised the following: author, year of publication, average score of critical reading learning ability using cooperative learning model, standard deviation, sample size, t-count value, and effect sizes. All data collected through data collection instruments is then extracted using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V3 (CMA) software. This extraction process is essential for analyzing and organizing data from the various studies that have been selected, allowing researchers to obtain more comprehensive and accurate results. Data were obtained based on the data extraction results from 28 studies, including complete mean, standard deviation, and sample size data.

Data Analysis

The data analysis from this study used Comprehensive Meta-Analysis V3 (CMA) software, which is equipped with various tests to ensure the findings' robustness. The first test is the heterogeneity test, which evaluates how uniform or varied the results of the analysed studies are. Furthermore, the most suitable effect model for the data, whether the fixed or random effect model, is selected to produce more precise and valid estimates. In the meta-analysis process, several vital calculations are performed, such as calculating effect sizes by standardizing mean differences using Hedges' g bias correction and calculating standard error effect sizes and mean standard differences to understand variability between studies. In addition, calculating the effect of the standard error summary, the lower and upper limits, the Z-value, and the hypothesis test is carried out to confirm the results obtained and ensure that the observed effects are not caused by mere coincidence. The summary effect was interpreted by describing the results in forest plots, which provided a clear visualization of the impact distribution between studies. This process also includes publication bias correction through plot funnel diagrams, which help identify whether there are publication biases that affect research outcomes(Borenstein et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2010)As a data analyst, the author is responsible for ensuring that all stages of this analysis are carried out appropriately, interpreting and presenting valid and reliable results, and ensuring that the conclusions drawn accurately reflectthe data collected.

Findings/Results

The results of the analysis conducted by the researcher with the help of the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) program have been compiled and presented in the form of a precise tabulation. This analysis involves various statistical calculations to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the findings of the multiple studies. Using CMA, researchers can systematically organise the data, provide a more comprehensive picture of the diverse research results, and assess the significance of the observed effects. The results can now be found in Table 3 below, which provides detailed and easy-to-understand information about the study's main findings.

Table 3. Meta-Analysis Results

| Model | Effect size and 95% confidence interval | Test of null(2-tail) | ||||||

| Number Studies | Point estimate | Standard error | Variance | Lower limit | Upper limit | Z-value | p-value | |

| Fixed | 28 | 0.784 | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.689 | 0.880 | 16.164 | 0.000 |

| Random | 28 | 0.939 | 0.192 | 0.037 | 0.563 | 1.315 | 4.893 | 0.000 |

The fixed model demonstrated a mean overall standard difference of 0.784 (95% CI, 0.689 to 0.880) with ap-value of 0.00 (<.05). The effect sizes derived from the random model revealed an overall standard difference in the mean of 0.939 (95% CI, 0.563 to 1.315), accompanied by a p-value of 0.00, which is also less than 0.05. When employing a cooperative learning model, these two meta-analyses suggest a positive association between effect sizes and critical reading learning. Consequently, critical reading learning utilising the collaborative learning model is more effective than critical reading learning that does not employ the cooperative learning model. Additionally, the study reported a substantial effect, given that the magnitude of both effect sizes exceeded 0.6. To observe the considerable impact of the two class models employed and the effect sizes greater than 0.6, the data from each study are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Study Effect Measures Included in the Study Studied

| Author and Year | Effect Size (d) | Standard error | Variance | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | Z-value | p-value |

| Aghaei et al. (2014) | 1.252 | 0.309 | 0.096 | 0.646 | 1.858 | 4.047 | 0.000 |

| Aghajani and Gholamrezapour (2019) | 0.249 | 0.151 | 0.023 | -0.048 | 0.545 | 1.644 | 0.100 |

| Akın et al. (2015) | 0.916 | 0.286 | 0.082 | 0.355 | 1.477 | 3.202 | 0.001 |

| Albeckay (2014) | 0.301 | 0.297 | 0.088 | -0.280 | 0.882 | 1.016 | 0.310 |

| Allagui (2021) | 2.431 | 0.362 | 0.131 | 1.721 | 3.141 | 6.709 | 0.000 |

| Ardhian et al. (2020) | 1.586 | 0.242 | 0.058 | 1.113 | 2.060 | 6.563 | 0.000 |

| Asmara et al. (2023) | 0.163 | 0.317 | 0.100 | -0.458 | 0.784 | 0.514 | 0.607 |

| Bernal et al. (2023) | 1.459 | 0.163 | 0.027 | 1.140 | 1.778 | 8.960 | 0.000 |

| Churat et al. (2022) | 1.218 | 0.385 | 0.148 | 0.463 | 1.972 | 3.164 | 0.002 |

| Darvenkumar and Devi (2022) | 2.828 | 0.246 | 0.061 | 2.346 | 3.311 | 11.488 | 0.000 |

| Halim (2011) | 7.544 | 0.520 | 0.270 | 6.525 | 8.563 | 14.506 | 0.000 |

| Hariyati and Ahmadi (2019) | 0.748 | 0.244 | 0.059 | 0.270 | 1.226 | 3.067 | 0.002 |

| Hazaymeh and Alomery (2022) | 0.068 | 0.309 | 0.095 | -0.537 | 0.673 | 0.222 | 0.824 |

| Hromova et al. (2022) | 1.049 | 0.218 | 0.047 | 0.623 | 1.476 | 4.820 | 0.000 |

| Khamkhong (2018) | 0.960 | 0.249 | 0.062 | 0.472 | 1.448 | 3.856 | 0.000 |

| Khonamri and Karimabadi (2015) | 0.093 | 0.316 | 0.100 | -0.527 | 0.713 | 0.295 | 0.768 |

| Koray and Çetinkılıç (2020) | 0.161 | 0.286 | 0.082 | -0.400 | 0.722 | 0.562 | 0.574 |

| Lee (2015) | 0.494 | 0.233 | 0.054 | 0.037 | 0.950 | 2.121 | 0.034 |

| Lee (2017) | 0.012 | 0.239 | 0.057 | -0.456 | 0.481 | 0.052 | 0.959 |

| Mekuria et al. (2024) | -0.408 | 0.249 | 0.062 | -0.895 | 0.080 | -1.639 | 0.101 |

| Moghadam et al. (2021) | 0.182 | 0.283 | 0.080 | -0.374 | 0.737 | 0.641 | 0.521 |

| Mulcare and Shwedel (2017) | 0.050 | 0.267 | 0.071 | -0.474 | 0.574 | 0.186 | 0.853 |

| Shalaby (2021) | 0.576 | 0.263 | 0.069 | 0.060 | 1.092 | 2.186 | 0.029 |

| Shokrpour et al., (2013) | 0.050 | 0.258 | 0.067 | -0.456 | 0.556 | 0.195 | 0.846 |

| Sultan et al. (2017) | -0.038 | 0.267 | 0.071 | -0.561 | 0.486 | -0.140 | 0.888 |

| Varaporn and Sitthitikul (2019) | 0.241 | 0.254 | 0.065 | -0.257 | 0.740 | 0.949 | 0.343 |

| Yang et al. (2022) | 1.705 | 0.330 | 0.109 | 1.058 | 2.352 | 5.162 | 0.000 |

| Yulian (2021) | 1.545 | 0.265 | 0.070 | 1.026 | 2.064 | 5.831 | 0.000 |

Based on the description in Table 4, it can be seen that the effect size of the 28 articles analyzed showed two studies with negative results. In comparison, the other 13 articles had a lower limit that was also negative, and two articles showed negative results on Z-Value. As illustrated in Table 4, these results provide an overview of the effect size and p-values for each study analyzed. This data is an essential basis for conducting further analyses in this study. In addition, the data presented in Table 4 will be used to examine the heterogeneity between studies to understand how critical reading learning using a cooperative learning model affects the results obtained. The results of this heterogeneity test, which measures the variation between the studies used in the analysis, can be found in Table 5, which will be the primary reference in the subsequent analysis process.

Table 5. Results of Effect Size Heterogeneity Analysis

| Heterogeneity | Tau-Squared | ||||||

| Q-value | df (Q) | p-value | I-Squared | Tau Squared | Standard Error | Variance | Tau |

| 413.089 | 27 | 0.000 | 93.464 | 0.931 | 0.299 | 0.089 | 0.965 |

| p<.05 |

The I2 statistic for heterogeneity was determined to be 93.464 (93.46%), p = 0.000 (p < 0.05), indicating that the alternative hypothesis was accepted. The findings of this study demonstrate significant variation among the studies selected for this investigation. Consequently, estimating the average impact size of the 28 studies investigated using random effects is more appropriate. These findings imply that further investigation into the moderate factors influencing the Y variable may be advantageous.

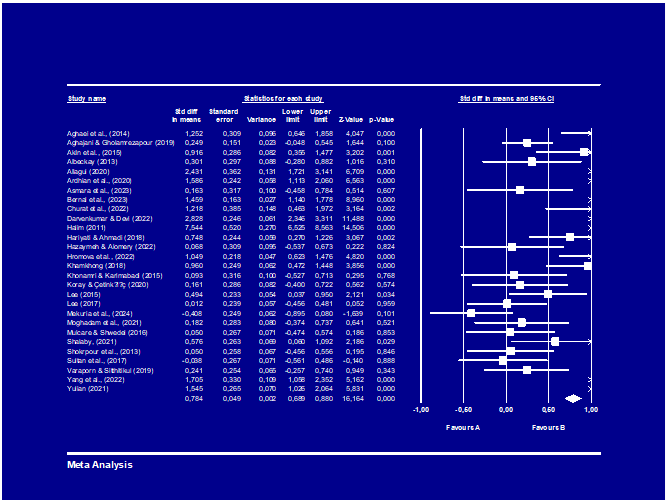

As illustrated in Figure 2, a forest plot for critical reading learning employing a cooperative learning model is presented. Given the continuous variation in critical reading ability outcomes, this forest plot features an unaffected line designated as 0. The average effect sizes can be summarised on the treatment side by utilising critical reading learning and employing a cooperative learning model towards the positive side of the graph, according to the direction of the set effect sizes. The forest plot in Figure 2 reveals that, among the 28 studies conducted, two exhibit a less significant influence measure or negative z-value. The remaining 26 studies demonstrate a significance of <0.05 and a positive z-value. This observation suggests that the majority of studies exhibit consistent effect sizes.

Figure 2. Forest Plot

Publication Bias

As illustrated in Figure 3, the funnel plot for critical reading learning using a cooperative learning model demonstrates a symmetrical distribution of the estimated effect around the centerline. This suggests the possibility of including related trials in the analysis. The symmetry of the funnel plot findings on the axis remains uncertain, necessitating the application of Egger's test for further testing.

Figure 3. Funnel Plot of Precision by Std.diff.in the sense of and with Standard Error

The regression test findings demonstrate a substantial, albeit less pronounced, deviation from zero, as indicated by the P value 0.05 for both the one-tailed and two-tailed tests. The researcher will consider the P value of 0.05 for the two-tailed test, which supports the null hypothesis and suggests the presence of significant asymmetry, thereby ensuring the result is not biased. Furthermore, publication bias was identified by implementing the Begg and Muzambdar rating correlation and the classic fail-safe N, as demonstrated in Tables 6 and 7.

Table 6. Results of Begg and Muzambdar Rank Correlation

| Kendall`s S statistic (P-Q) | Kendall`s tau without continuity correction | Kendall`s tau with continuity correction | ||||||

| Tau | z-value for tau | p-value (1- tailed) | p-value (2- tailed) | Tau | z-value for tau | p-value (1- tailed) | p-value (2- tailed) | |

| 56.00000 | 0.14815 | 1.10637 | 0.13428 | 0.26857 | 0.14550 | 1.08661 | 0.13860 | 0.27721 |

Table 7. Hasil N fail-safe classic

| Z-value for observed studies | The p-value for observed studies | Alpha | Tails | Z for alpha | Number of observed studies | Number of missing studies that would bring p-value to > alpha |

| 17.04203 | .00000 | 0.5000 | 2 | 1.95996 | 28 | 2089 |

The missing study score was recorded in 2089; this figure indicates the existence of potential research that may not be published or detected in this analysis, which could lead to bias. This suggests that some relevant studies may not be represented in the data analyzed, which often influences the results of meta-analyses. However, the significance value of Kendall from the correlation of the Begg and Muzambdar ratings exceeding 0.5000 on both sides provides evidence that there was no significant bias in this study. Based on these parameters, it can be concluded that the studies used in this meta-analysis do not show substantial bias, so the results obtained can be considered valid and trustworthy.

Moderator Analysis

Education Level Moderator Analysis

Based on the analysis, the effect sizes obtained are known to be heterogeneous. The effect sizes included in the study are then calculated and compared according to the level of education, starting from elementary school, junior high school, high school, and university. The results of this comparison are given in Table 8.

Table 8. Results of Moderator Analysis with Random Effects Model for Education Level

| Confidence Interval (95%) | |||||||||||

| Moderator (Education Level) | Number of Study (k) | Effect Size (d) | Standard error | Variance | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | z | p | Q | Df(Q) | p |

| Primary School | 2 | 1.307 | 0.185 | 0.034 | 0.945 | 1.669 | 7.079 | 0.000 | 3.204 | 1 | 0.073 |

| Middle School | 2 | 1.142 | 0.142 | 0.020 | 0.864 | 1.419 | 8.066 | 0.000 | 15.537 | 1 | 0.000 |

| High School | 2 | 1.498 | 0.251 | 0.063 | 1.007 | 1.990 | 5.978 | 0.000 | 0.922 | 1 | 0.337 |

| University | 22 | 0.649 | 0.055 | 0.003 | 0.541 | 0.757 | 11.784 | 0.000 | 363.938 | 21 | 0.000 |

| Between Groups | 412.115 | 27 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Total | 28 | 0.784 | 0.049 | 0.002 | 0.689 | 0.880 | 16.164 | 0.000 |

The effect sizes (d = 1.307) of the study on critical reading learning using a cooperative learning model, in which student research subjects in elementary school (k = 2) were involved, were categorized as high and did not show statistical significance (z = 7.079, p <.05). Additionally, the effect size score (d = 1.142) from the study conducted with middle school students (k = 2) was also high and showed statistical significance (z = 8.066, p <.05). Conversely, the effect size score (d = 1.498) from the study conducted with students in high school (k = 2) was included in the high category and did not show statistical significance (z = 5.978, p <.05). The subsequent data, pertaining to the highest level of education, exhibited an effect size score (d = 0.649) for studies conducted with students at universities (k = 22), which fell within the intermediate range and demonstrated statistical significance (z = 11.784, p <.05). The results of the analysis between groups demonstrated that the score of the influence of research with different levels of education in critical reading learning using the cooperative learning model was statistically significant (QBG = 412.115, sd = 27, p = 0.000).

Analysis of the State Moderator Study

A quantitative analysis was conducted to calculate and compare the effect sizes for the data of each study included in the study, with the analysis performed according to the author's country of origin. The results of the comparison that were analysed are presented in Table 9.

Table 9. Results of Moderator Analysis with Random Effects Model of Countries Where the Study Was Conducted

| Confidence Interval (95%) | |||||||||||

| Moderator (Education Level) | Number of Study (k) | Effect Size (d) | Standard error | Variance | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | z | p | Q | Df(Q) | p |

| Colombia | 1 | 1.453 | 0.162 | 0.026 | 1.135 | 1.771 | 8.960 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Ethiopia | 1 | -0.403 | 0.246 | 0.060 | -0.885 | 0.079 | -1.639 | 0.101 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 |

| India | 1 | 2.812 | 0.245 | 0.060 | 2.332 | 3.291 | 11.488 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Indonesia | 5 | 0.859 | 0.116 | 0.014 | 0.631 | 1.087 | 7.382 | 0.000 | 32.270 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Iran | 4 | 0.352 | 0.113 | 0.013 | 0.130 | 0.573 | 3.107 | 0.002 | 9.927 | 3 | 0.019 |

| Libya | 1 | 0.296 | 0.291 | 0.085 | -0275 | 0.0867 | 1.016 | 0.310 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Mesir | 2 | 1.969 | 0.232 | 0.054 | 1.513 | 2.424 | 8.475 | 0.000 | 143.393 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Taiwan | 2 | 0.257 | 0.165 | 0.027 | -0067 | 0.580 | 1.554 | 0.120 | 2.084 | 1 | 0.149 |

| Thailand | 5 | 0.692 | 0.125 | 0.016 | 0.448 | 0.937 | 5.552 | 0.000 | 21.644 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Turkey | 2 | 0.530 | 0.199 | 0.040 | 0.140 | 0.921 | 2.661 | 0.008 | 3.488 | 1 | 0.062 |

| UEA | 2 | 1.042 | 0.231 | 0.053 | 0.589 | 1.494 | 4.510 | 0.000 | 24.723 | 1 | 0.000 |

| Ukraina | 1 | 1.041 | 0.216 | 0.047 | 0.618 | 1.464 | 4.820 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 |

| United States | 1 | 0.049 | 0.264 | 0.069 | -0.468 | 0.566 | 0.186 | 0.853 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Between Groups | 413.089 | 27 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Total | 28 | 0.774 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.680 | 0.868 | 16.134 | 0.000 |

An examination of the data presented in Table 9 reveals that the effect size (d = 1.453) of the study conducted in Colombia (k = 1) employing a cooperative learning model for critical reading instruction attained a high level, demonstrating statistical significance (z = 8.960, p < .05). Conversely, the study conducted in Ethiopia (k = 1) exhibited an effect sizes score (d = -0.403), which was classified as low and did not demonstrate statistical significance (z = -1.639, p <.05). Subsequent research undertaken in India yielded a score of effect sizes (d = 2.812) with (k = 1), and the findings were classified within the high category, demonstrating statistical significance (z = 11.488, p <.05). A parallel study undertaken in Indonesia yielded an effect sizes score (d = 0.859) with a total of five studies (k = 5). The results were classified within the high category. They demonstrated statistical significance (z = 7.382, p <.05). Research conducted in Iran demonstrated that the effect sizes score (d = 0.352) with the number of studies as many as 4 (k = 4) and the results were in the intermediate category and showed statistical significance (z = 3.107, p > 0.05). Subsequent research conducted in Libya yielded an effect size score (d = 0.296) with the number of 1 study (k = 1). The study results were included in the intermediate category and were not statistically significant (z = 1.016, p > 0.05). A similar study conducted in Egypt demonstrated that the effect sizes score (d = 1.969) with the number of studies as many as 2 (k = 2), the results of the study were interpreted in the high category and showed statistical significance (z = 8.475, p > 0.05).

Meanwhile, subsequent research in Taiwan demonstrated that the effect size score (d = 0.257) corresponded to several studies of 2 (k = 2). The study findings indicated that the intermediate category did not demonstrate statistical significance (z = 1.554, p > 0.05). Similar studies conducted in Thailand yielded an effect size score (d = 0.692) with five studies (k = 5). The results were included in the high category and showed statistical significance (z = 5.552, p>0.05). Research conducted in Turkey yielded an effect size score (d = 0.530) with two studies (k = 2). The data were interpreted into the intermediate category and showed statistical significance (z = 2.661, p > 0.05). Concurrent studies have been conducted in the UAE, yielding an effect size score (d = 1.042) of 2 (k = 2). The findings of these studies were classified within the high category and demonstrated a level of statistical significance (z = 4.510, p > 0.05). A similar study in Ukraine showed the effect size score (d = 1.041) with several studies of 1 (k = 1). The data were interpreted into a high category and showed statistical significance (z = 4.820, p > 0.05). In contrast, the most recent study undertaken in the United States yielded an effect size score (d = 1.041) with several studies of 1 (k = 1). The data were classified within the vertical category and did not demonstrate a level of statistical significance (z = 0.186, p > 0.05). The results of the inter-group analysis revealed that the effect sizes scores of studies conducted in various countries in critical reading learning using the cooperative learning model were statistically significant (QGB = 413.089, sd = 27, p = 0.000).

Some studies conducted in Ethiopia, Libya, and the United States showed a P value of 1,000, indicating that applying cooperative learning models in such contexts had a weak or negative effect on improving critical reading skills. This high P-value indicates no significant difference or substantial relationship between using cooperative models and improving critical reading skills in students in these regions. This phenomenon raises the question of why models proven effective in many studies show suboptimal results in these countries. To answer this, it is important to understand that the effectiveness of a learning model does not solely depend on the method itself but is also highly determined by the social, cultural, and educational context surrounding it.

In Ethiopia, the main challenges faced in the world of education are closely related to limited resources, both in terms of infrastructure, learning materials, and training for teachers (Ghoulam et al., 2024; X. Wang et al., 2023). Cooperative learning models require active student involvement, good teacher facilitation, and a classroom atmosphere conducive to collaboration (Keramati & Gillies, 2022) However, in crowded school conditions, lack of facilities, and a low teacher-to-student ratio, this strategy often does not work as expected. Teachers may not have adequate training to implement this approach effectively, so the learning process becomes directionless and the goal of improving critical reading skills is not optimally achieved. Therefore, the local context, such as in Ethiopia, is a key factor in understanding the results shown by the P value.

Meanwhile, in Libya, the volatile socio-political dynamics of recent decades have had a significant impact on the Education sector (Eren, 2021; Şener et al., 2023) Prolonged conflicts, inconsistent curriculum changes, and lack of institutional stability cause the educational process to run suboptimally. In such a situation, the cooperative learning model, which requires stability of the classroom environment as well as continuity in implementation (Subiyantari & Muslim, 2019) is very likely not to be implemented effectively. In addition, uncertainty in the education system can make it difficult for teachers and students to follow new learning structures or those that require active participation, as with cooperative learning. Therefore, it is natural that research in Libya shows low effectiveness in improving critical reading skills, reflected in the high P value.

Unlike the previous two countries, the results of a study in the United States that also showed a P value of 1,000 seemed to be influenced by the complexity of the highly diverse and fragmented education system. Although America is known for having an advanced education system, the variation in teaching approaches between states, districts, and even between schools makes the consistency of the implementation of cooperative learning models a challenge (Eren, 2021; Şener et al., 2023) In some cases, schools place more emphasis on standardized test results than the development of critical thinking skills, so there is limited space for the application of collaboration-based learning models. In addition, the individualization factor in learning is very high in America can cause students to be less accustomed to working in teams, so the effectiveness of cooperative models in shaping critical reading skills is not fully achieved. Therefore, negative or weak results in American research must be understood in that context.

Thus, high P values in studies from Ethiopia, Libya, and the United States do not solely reflect the ineffectiveness of cooperative learning models universally, but rather reflect the complexity of the local challenges faced in their implementation. Geographical, social, cultural, and educational policy contexts greatly influence the extent to which a model can work optimally. Therefore, the results of the meta-analysis must be comprehensively understood, taking into account contextual differences between countries and regions. This understanding is important so that the conclusions drawn are not misleading generalizations, but are reflective and adaptive to the reality on the ground.

Publication Type Moderator Analysis

Effect sizes for research data included in various forms of publications, such as scientific articles and proceedings, serve as a metric for conducting comparative analyses of research findings. The results of these comparative analyses are presented in Table 10.

Table 10. Results of Moderator Analysis with Random Effects Model for Publication Types

| Confidence Interval (95%) | |||||||||||

| Moderator (Education Level) | Number of Study (k) | Effect Size (d) | Standard error | Variance | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | z | p | Q | Df(Q) | p |

| Journal | 23 | 0.792 | 0.052 | 0.003 | 0.691 | 0.894 | 15.274 | 0.000 | 402.937 | 22 | 0.000 |

| Proceding | 5 | 0.666 | 0.126 | 0.016 | 0.419 | 0.914 | 5.278 | 0.000 | 9.300 | 4 | 0.054 |

| Between Groups | 413.089 | 27 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Total | 28 | 0.774 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.680 | 0.868 | 16.134 | 0.000 |

As illustrated in Table 10, the critical reading learning study employing the cooperative learning model, disseminated through scientific articles (k = 23), demonstrates a substantial effect size (d = 0.792). This study exhibits statistical significance (z = 15.274, p < .05), suggesting a high level of efficacy. The results of the effect sizes score (d = 0.666) from the study published in proceedings (k = 5) were included in the intermediate category. They showed statistically significant results (z = 5.278, p <.05). The findings of the inter-group analysis demonstrated that the score of the influence of research with different types of publications in critical reading learning using the cooperative learning model was statistically significant (QGB = 413.089, df = 27, p = 0.000).

Moderator Analysis of Types of Learning Models

The effect sizes for the research data incorporated into the learning model, which encompasses direct learning, conventional learning, cooperative learning, scientific learning, and traditional learning, serve as a metric for comparative analysis. Table 11 elucidates the outcomes of this comparative analysis.

Table 11. Results of Moderator Analysis with Random Effect Model on Learning Model

| Confidence Interval (95%) | |||||||||||

| Moderator (Education Level) | Number of Study (k) | Effect Size (d) | Standard error | Variance | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | z | p | Q | Df(Q) | p |

| Direct Learning | 7 | 0.562 | 0.103 | 0.011 | 0.360 | 0.764 | 5.455 | 0.000 | 59.867 | 6 | 0.000 |

| Conventional | 5 | 0.798 | 0.104 | 0.011 | 0.594 | 1.002 | 7.665 | 0.000 | 187.933 | 4 | 0.000 |

| Cooperative | 13 | 0.848 | 0.075 | 0.006 | 0.702 | 0.994 | 11.364 | 0.000 | 127.339 | 12 | 0.000 |

| Scientific | 2 | 0.073 | 0.181 | 0.033 | -0282 | 0.428 | 0.401 | 0.688 | 0.158 | 1 | 0.691 |

| Traditional | 1 | 1.453 | 0.162 | 0.026 | 1.135 | 1.771 | 8.960 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0 | 1.000 |

| Between Groups | 413.089 | 27 | 0.000 | ||||||||

| Total | 28 | 0.774 | 0.048 | 0.002 | 0.680 | 0.868 | 16.134 | 0.000 |

As demonstrated in Table 11, the critical reading learning study employing a cooperative learning model, which was taught using a direct learning model (k = 7), exhibited a substantial effect size (d = 0.562). This effect size was categorized within the high category and demonstrated statistical significance (z = 5.455, p < .05). The results of the effect sizes score (d = 0.798) from the research on critical reading learning using the conventional learning model (k = 5) were included in the high category and showed a statistically significant level (z = 7.665, p <.05). Additionally, the results of the effect sizes score (d = 0.848) from the research on critical reading learning using the cooperative learning model (k = 13) were interpreted in the high category and showed a statistically significant level (z = 11.364, p <.05). Conversely, the results of the research on critical reading learning taught using the scientific method yielded an effect sizes score (d = 0.073) with a total of 2 (k = 2). The analysis results of the effect sizes score were included in the intermediate category. They did not show a statistically significant level (z = 0.401, p <.05). On the other hand, results about the conventional model of teaching critical reading showed an effect size score (d = 1.453) with a total of 1 (k = 1). The effect sizes score analysis indicated a high category which showed significance at the level of (z = 8.960, p <.05). The results of the inter-group analysis revealed that learning model of the study and determination of the achievement of critical reading learning through the cooperative learning model was significant (QGB = 413.089, df = 27, p = 0.000).

Conclusion

This meta-analysis reveals that the cooperative learning model significantly impacts the improvement of critical reading abilities(Khonamri & Karimabadi, 2015).The reviewed studies from 2011 to 2024 show how the cooperative learning model has been effective in promoting higher order thinking skills and text analysis amongst students(Harefa, 2020; Setiawan et al., 2023; Subiyantari & Muslim, 2019).The result shows that there is a positive improvement in the students’ cognitive engagement with the reading materials when cooperative learning is used. Thus, the students' critical reading skills are improved(Jufrida et al., 2021; Safi’i et al., 2021).Extant literature, including that gathered for this study and prior reports, demonstrates supporting evidence for effectiveness of the cooperative learning model towards instruction on critical reading skills. These studies seeking to measure the impact of this learning model on the cognitive skills of students reported more or less consistent findings though differed in the sum of data and diversity of methods that this study utilized. Making use of an expanded temporal scope allows for a more comprehensive understanding of how cooperative learning can be used in different contexts. It provides a wider angle at its effectiveness for the development of students' critical reading skills.

This study’s findings show that the application of the cooperative learning model improves students’ social(Çepni & Öner, 2015; Durlak et al., 2011; Keramati & Gillies, 2022),as well as cognitive skills(Viado& Jo A. Espiritu Department, 2023).Students' social skills in articulating and critiquing readings have been shown to be enhanced through group discussions and collaborative activities(Abdelhalim, 2017; Fatemipour & Hashemi, 2016; Wanzek et al., 2010).The development of a broad perspective concerning the text is one of the most important goals(Alghonaim, 2020; Mete, 2020).These outcomes commendably corroborate that advocacy of collaboration-based learning is in its potential to improve critical reading skills, which this study aims to achieve.

The findings of this research are important when considering how policies related to educational provisions can be constructed towards supporting the development of critical reading skills. This illustrates the need to adopt a cooperative learning model into the teaching curriculum, especially on high order critical subjects(Kim, 2020).Thus, this study richly adds to the already existing efforts towards the improvement of academic instructional quality through a more participatory and collaborative style(Azizah et al., 2024; Bermillo & Merto, 2022).The results of the study confirmed the validity of the cooperative learning model in developing critical reading skills which stemmed from the social interaction of the study group(Ahmadishokouh et al., 2024).Such interactions have been shown to increase students’ participation in the learning process, stimulate the sharing of ideas, and encourage positive critiques among classmates.

These aspects have improved students' understanding and ability to assess texts(Jufrida et al., 2021).This model's social and collaborative aspects have been pointed out as the significant reasons for improving students’ intellectual engagement(Khonamri & Karimabadi, 2015).Upon reviewing these discoveries, it is evident that there is a need for the adoption of more cooperative learning models in teaching critical reading. Teachers need to be included in the processes of training and development of the appropriate competencies to allow effective cooperative learning facilitation. Besides, there has to be a change on the allocation of time so that students would have enough time to work together in analyzing and discussing literary texts. With these approaches, it is expected that students will improve in their critical reading abilities over time.

The focal results of this research show that the cooperative learning model has a more significant relative impact on the development of critical reading skills than other models of learning. The meta-analysis study showed that using this model goes beyond helping students understand textual materials. It also helps actively engage them to argue, make inferences, and evaluate the materials received. Such meta-cognition processes of information comprehension supporting the notion of critical reading skills as sophisticated skills are best trained in inter-student cooperation. These outcomes suggest a new perspective regarding the strength of cooperative learning which has been overlooked.

The approach that integrates information technology into education as a science, specifically the theory of cooperative learning and critical reading skills, has dramatically advanced due to this research.Theoretically, this study enhances the existing knowledge on the effectiveness of cooperative learning models in the context of critical reading skills. This subject has been extensively explored in the realm of higher education. From a practical standpoint, this study offers empirical evidence that can serve as a reference for educators in designing more interactive and collaborative learning strategies, which, in turn, can enhance the quality of student literacy. Consequently, the cooperative learning model is applicable in formal education settings and can be adapted to various other learning contexts.

Nonetheless, this study's findings are very promising, but some limitations must be observed. For example, the study only examines previously published studies and has not directly tested the application of cooperative learning models in the field. Therefore, further development can focus on research that implements the model at different levels of education and cultural contexts. More in-depth studies on the inhibiting factors in the application of this model can also provide more comprehensive insights to improve its effectiveness in the future.

This study accommodates the diversity of findings arising from various cooperative learning strategies, differences in contexts in the education system, variations in instructional designs, and the heterogeneity of the sample used in the studies analyzed. The cooperative learning model is not a single approach, but consists of various strategies such as Jigsaw, Think-Pair-Share, Student Teams-Achievement Divisions (STAD), and Numbered Heads Together (Capar & Tarim, 2015; Gull & Shehzad, 2015) each of which has unique characteristics and varying levels of effectiveness depending on how they are applied (Hayati et al., 2023; Keramati & Gillies, 2022). Some strategies show high effectiveness in improving critical reading skills, while others have only a moderate or even weak impact. This suggests that the effectiveness of the cooperative model is highly dependent on the suitability between the strategies used with the needs and characteristics of the learners, as well as the supportive learning environment (Chen et al., 2020; Varvarigou,2014) Differences in the context of education systems in different countries are also important factors that affect the results of the research (Bajrami, 2019)because factors such as curriculum policies, teacher capacity, and learning culture can shape the way cooperative models are applied in the classroom (Nieto & Ramos, 2015) In addition, variations in instructional design—including the duration of implementation, technology integration, and the form of assessment used—can also affect learning outcomes (Efremova et al., 2020; Morris et al., 2021), particularly in critical reading skills that are complex and require deep understanding (Shalaby, 2021). The heterogeneity of the sample used in the study, both in terms of age, education level, and socio-economic background, also contributed to the diversity of results found in this meta-analysis (Cummins et al.,2018). Therefore, going forward, further research is strongly recommended to explore differences in cooperative learning methods in more depth, paying attention to contextual and individual variables that can moderate the effectiveness of learning strategies. Future research may also focus on the development of adaptive instructional designs that take into account the specific needs of students as well as the application of cooperative models in various educational ecosystems, both in developing and developed countries. Thus, a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics of the effectiveness of cooperative learning can be achieved and become the basis for more targeted education policy making.

Recommendation

The findings of this study offer several significant recommendations for developing critical reading skills through a cooperative learning model. Educators are advised to adopt this model more broadly, given its effectiveness in improving student participation and critical reading and thinking skills.Moreover, teachers are required to undergo specific training on the implementation of cooperative learning models which includes practical approaches and evaluation of their effectiveness. It is also essential to further examine the different contexts within which different cooperative learning models are implemented to determine their applicability and effectiveness across all educational spheres.

Limitation

Notwithstanding, it is critical to note the limitations of the study. First, the analysis was based on existing literature which does not allow for inclusion of any unpublished work. Second, the diversity in research methods and designs of the provided literature make synthesizing an overarching conclusion infeasible. Moreover, the study did not incorporate all possible learning environments, so the findings may not be completely applicable across different settings. These shortcomings are bound to be encountered in the future and will hopefully allow the issue of the effectiveness of cooperative learning models to be more comprehensively understood.

This research received support from the Center for Higher Education Funding and Assessment (PPAPT) and the Education Fund Management Institute (LPDP) through the Indonesian Education Scholarship (BPI) of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, with the scholarship recipient's identification number 202329112981.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that neither real nor perceived conflicts of interest exist. Artificial intelligence was not used in the preparation of this paper.

Generative AI Statement

The author has not used generative AI or AI-supported technologies.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Setiawan: Conceptualization, design, analysis/interpretation, and writing. Suwandi: conceptualization, final approval, reviewing, and supervision. Rohmadi: reviewing and critical revision of the manuscript.