Introduction

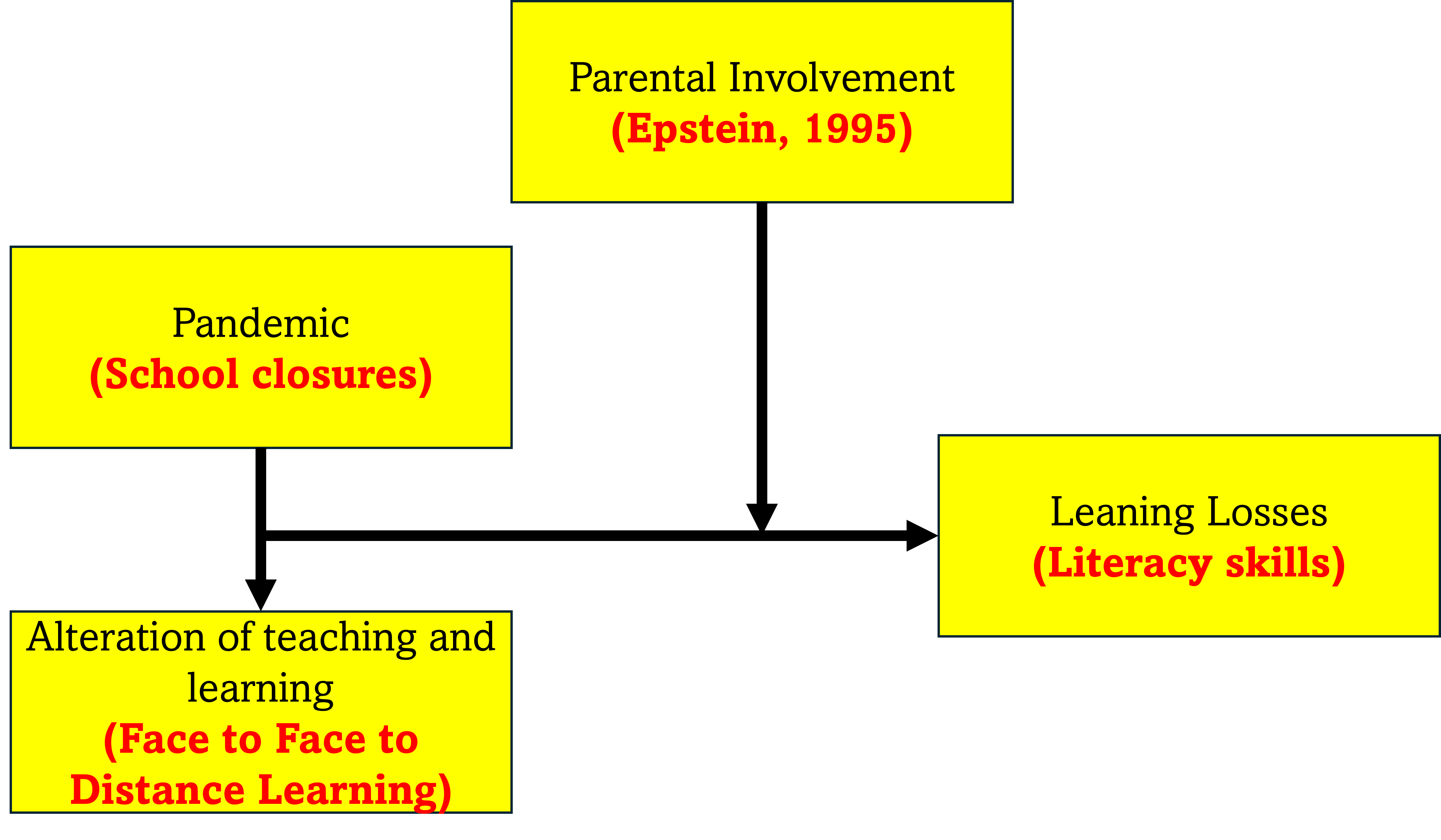

In recent years, the global education sector has faced unprecedented challenges, primarily triggered by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. As shown in Figure 1, the pandemic, which emerged in late 2019, caused significant disruptions to traditional educational norms and practices, forcing a swift and widespread adoption of blended and distance learning models. The closure of educational institutions worldwide and the rapid shift to online learning fundamentally altered how education is delivered (Tadesse &Muluye, 2020). This disruption raised serious concerns about potential learning losses, particularly among children who experienced regular school routine interruptions.

Learning losses, defined as the cognitive decline or regression in knowledge and skills resulting from prolonged interruptions or gaps in a child's regular educational program, have become a critical issue in education. These losses are closely linked to learning poverty, a term that describes the inability of children to attain basic literacy skills by a certain age (Azevedo et al., 2021). The pandemic's global impact has highlighted the urgency of addressing these learning deficits, as many children worldwide have fallen behind academically due to the sudden and prolonged shift to remote learning (Donohue & Miller, 2020).

The widespread closure of schools and universities during the pandemic was necessary to reduce the virus's spread and mortality rates (S.Burgess & Sievertsen, 2020). However, this drastic action had far-reaching consequences for the formal teaching and learning process, compelling educators and children alike to adapt to online learning platforms (Fernández-Bataneroet al., 2022). The abrupt transition to remote education presented numerous challenges, particularly for primary school children, who struggled to keep up with their studies. As a result, a significant proportion of young children were left behind, with many lacking the foundational literacy skills necessary for academic success—an alarming manifestation of learning poverty (Kim et al., 2021).

In the face of these challenges, the role of parental and family involvement in home learning has become increasingly important. Adapting the parental involvement framework by Epstein (2010), research has consistently shown that parental engagement in their children's education is a key factor in mitigating learning losses and promoting academic success. Parental involvement can take various forms, including supporting children's learning at home, participating in school-organized activities, and fostering a positive educational environment (Đurišić&Bunijevac, 2017). Studies have shown that children actively involved in their education tend to achieve higher academic outcomes, as their parents' support enhances learning and motivation (Suizzo, 2007). In the pandemic, the significance of parental involvement has been further amplified, as parents have had to take on a more active role in facilitating their children's learning amidst the disruptions to traditional schooling (Parczewska, 2020).

Results from the varied past research reflect the implementation of SDG 4 in order to foster better literacy among children through parental involvement. It is due to SDG 4 concentrates on providing particularly children and young people with learning opportunities which cover quality and easy access to education to improve their literacy and numeracy (Fazri, 2024). Therefore, this study aims to comprehensively understand the existing literature on 'Home Learning' using a bibliometric approach as the way to view the children’s literacy and the parental involvement. This study analyses literature related to home learning to achieve this objective. Through applying two distinct bibliometric analyses, the research addresses a critical gap in the field, providing valuable insights into past, present, and future research directions on the role of home learning in mitigating learning poverty. The study objectives, aligned with the specific bibliometric analyses, are as follows:

To assess the most influential past research andanalysecurrent trends in home learning through co-citation analysis.

To identify emerging trends in home learning through co-word analysis.

Figure 1. Justification of Study Through Adaptation of Epstein (2010) Parental Involvement Framework

Methodology

Bibliometric analysis provides a reliable method for understanding and evaluating scholarly communication and research trends. This approach uses statistical and mathematical techniques to quantify and examine elements such as publications, citations, and keywords (Pamuk, 2022). It is valuable for analyzing academic research and addressing learning gaps, as it helps researchers identify important publications, influential authors, and key institutions (Tahiruet al., 2023). Additionally, it provides insights into the evolution and dynamics of the research field while highlighting emerging trends (Wang & Si, 2023)

An important part of bibliometric analysis involves co-citation analysis, which examines how often two documents are cited together (Zhao &Strotmann,2022). The idea is that documents cited together frequently likely share related content, methodologies, or research areas (Rani et al., 2022). This type of analysis can offer valuable insights into the intellectual landscape of home learning and learning loss mitigation. It can help to identify important publications, influential authors, and prevalent research themes in the field (Torres et al., 2022). Additionally, it can reveal connections between different areas of study and highlight emerging and declining topics within the field (Yan &Zhiping, 2023).

One important method is co-word or co-occurrence analysis, which examines how often keywords or terms appear together in publications (L. Zhang et al., 2022). The assumption is that words frequently appearing together are conceptually interconnected (Li et al., 2023). This type of analysis helps identify central themes and concepts in research on home learning and strategies to address learning loss. It visualizes the semantic structure within the field, showing the interconnectedness of different ideas (Sedighi, 2016). Additionally, co-word analysis can reveal emerging trends and shifts in research topics, thus guiding future studies and policy development (Fayzullinaet al., 2023).

By using these bibliometric methods, researchers can gain a comprehensive understanding of the current research landscape, identify knowledge gaps, and evaluate the impact of existing studies (Devi et al., 2024). This information is crucial for making informed decisions about funding, academic progress, and developing effective strategies to support distance learning and address learning challenges (van Eck & Waltman, 2010).

Search String

For the bibliometric analysis, the selection of articles was guided by specific inclusion criteria to ensure a focused and comprehensive review. The Web of Science (WoS) was chosen as the primary database due to its extensive coverage and rigorous indexing standards. WoS covers high-impact journals and offers tools for detailed citation analysis, making it ideal for assessing research trends and scientific impact (Gauri et al., 2023). In Table 1, the bibliometric analysis encompasses all relevant records from 2014 to 2023. The search was conducted using the TS field, which includes the title, abstract, and keywords of the publications, ensuring a thorough capture of pertinent studies. The key terms utilized were“homeliterac*”and“child*”reflecting a broad interest in the literature related to children's home literacy environments.

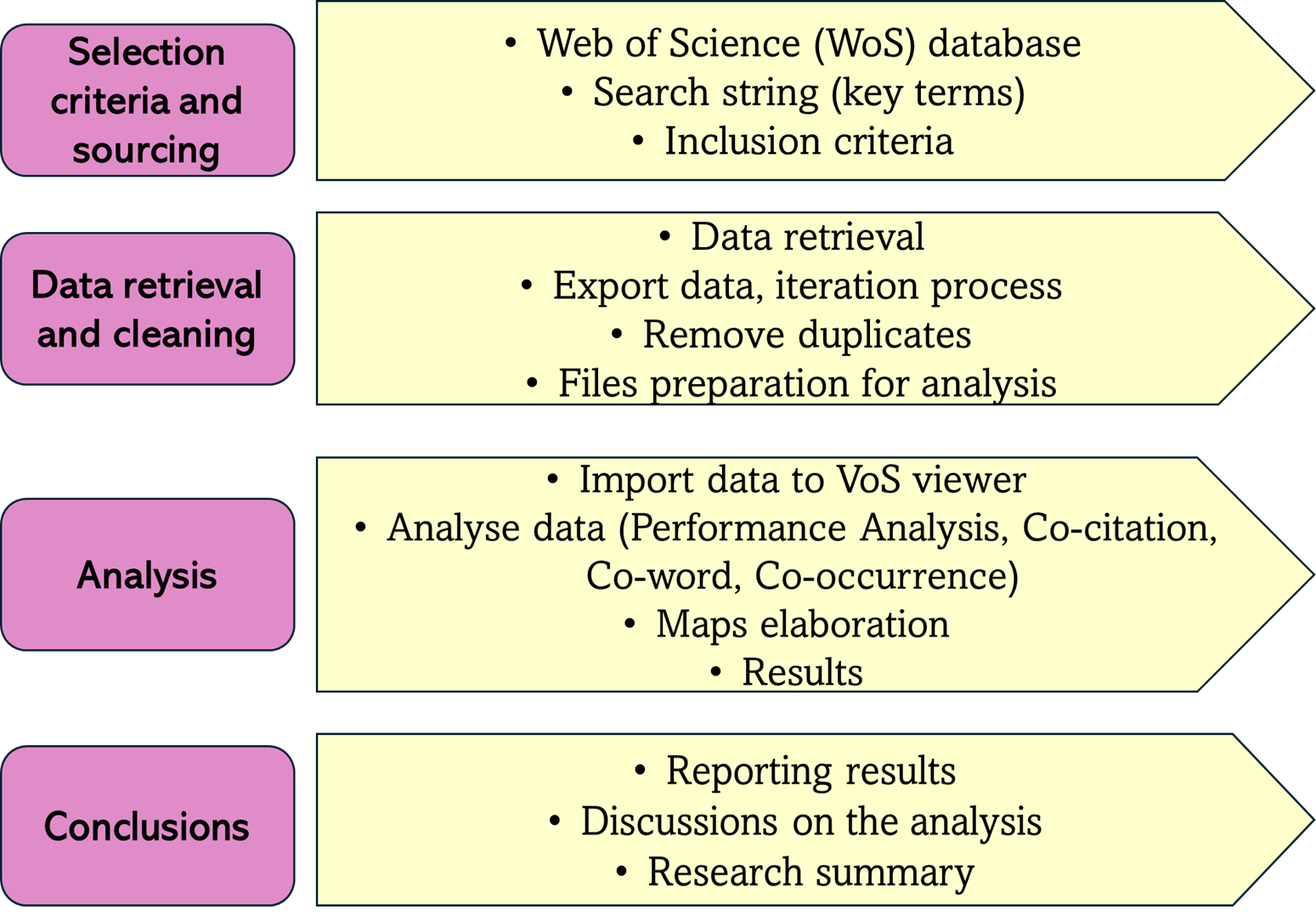

Furthermore, all Meso-level citation topics associated with these keywords were included, providing a detailed analysis of the thematic connections within the literature. Only articles and review articles published in English were considered, ensuring the selection of high-quality, peer-reviewed sources. This rigorous selection process ensures that the analysis provides a well-rounded and current overview of the research landscape in the chosen field (Georgiou et al., 2021; Suhaimi & Mahmud, 2022), which is visualised in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Bibliometric Analysis Methodology Framework (Adapted fromDanvila-del-Valle et al., 2019)

Table 1. Inclusion Criteria for Bibliometric Analysis

| WoS Database | ALL |

| Time period | 2014 to 2023 |

| Search field | TS |

| Search keywords | "home literac*" and "child*" |

| Citation Topics Meso | ALL |

| Document type | Article or Review Article |

| Language | English |

Results

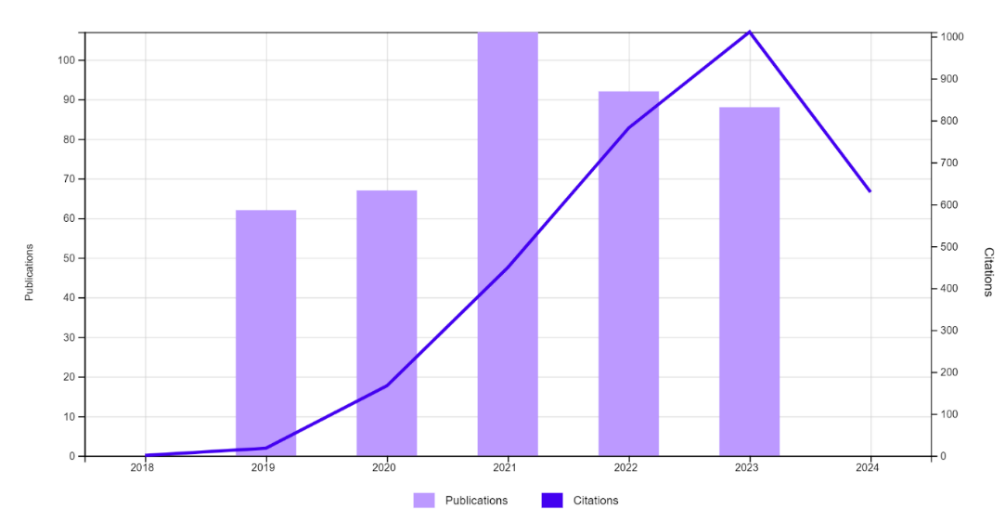

Bibliometric analysis of "Home Literacy" research using data from the Web of Science (Figure 3) reveals significant trends and impact in this evolving field. The analysis identified 416 relevant works, totaling 3,057 citations, resulting in an average of 7.35 citations per item. This moderate citation rate suggests each publication contributes meaningfully to academic discussions on home learning. The h-index of 25 indicates that at least 25 articles have been cited 25 times or more, highlighting key influential papers in the field. The interdisciplinary research encompasses education, psychology, sociology, and technology, reflecting the complex challenges and opportunities in home literacy. Although the existing research base is substantial, the trends in citations and h-index suggest the field remains active with room for further exploration. This growing academic interest aligns with global shifts towards remote and hybrid education models,emphasisingthe need for continued study in this area.

Figure 3.Quantity of Publications and Citations between 2014 and 2023

Performance Analysis

Of the 416 documents, 60 meet the threshold for selection in theVOSvieweron the most influential papers related to home literacy. Table 2 shows the top-ranked paper by Barger et al. (2019) on the relationship between parental involvement in schooling and children's adjustment leads to 151 citations. Other notable works include studies bySusperreguyet al. (2020) and Tan et al. (2020), which investigate parental attitudes and socio-economic factors in education. The prominence of these papers highlights the critical role of home environments and parental involvement in children's academic success, as evidenced by their high citation counts and broad scholarly influence.

In terms of leading journals (Table 3) in the field of home literacy, "Frontiers in Psychology" tops the list with 23 documents and 262 citations, indicating its central role in disseminating research on home learning. Journals like "Early Childhood Research Quarterly" and "Reading and Writing" also feature prominently, reflecting their significant contributions to early childhood education literature. These journals serve as essential platforms for researchers to share findings on the impact of home environments on children's literacy and overall academic development.

From Table 4 the most prolific authors in the field of home literacy, withTorppaMinna leading with 11 documents and 181 citations. Authors like Inoue Tomohiro andLerkkanenMarja-Kristiinaalso stand out for their substantial contributions. These researchers have significantly influenced the understanding of home literacy practices and their effects on children's reading skills. Their work, characterized by high citation counts and strong link strength, underscores the importance of ongoing research in this area to inform educational practices and policies.

In addition to the institutions that have made significant contributions to home learning research, the Chinese University of Hong Kong leads with 15 documents and 140 citations, followed by the University of Jyväskylä with 14 documents and 203 citations. The prominence of these institutions, especially those in China and Finland, reflects a global interest in understanding and improving home learning environments. These universities are pivotal in advancing research that informs educational practices and supports children's academic development across various contexts (refer Table 5).

Lastly, ranks countries by their contributions to home literacy research (Table 6), where the USA dominates with 161 documents and 1,151 citations, showcasing its leading role in this field. China and Canada follow, reflecting significant research activity in these regions. The global spread of influential research, particularly in developed nations, indicates widespread recognition of the importance of home learning environments. These countries' contributions are vital in shaping educational policies and practices that support children's learning and development worldwide.

Table 2. Performance Analysis by Documents

| Rank | Authors | Title | Citations |

| 1 | Barger et al. (2019) | The Relation Between Parents' Involvement in Children's Schooling and Children's Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis | 151 |

| 2 | Susperreguy et al. (2020) | Expanding the Home Numeracy Model to Chilean children: Relations among parental expectations, attitudes, activities, and children's mathematical outcomes | 74 |

| 3 | Tan et al. (2020) | Academic Benefits from Parental Involvement are Stratified by Parental Socioeconomic Status: A Meta-analysis | 68 |

| 4 | Lehrl et al. (2019) | Long-term and domain-specific relations between the early years home learning environment and students' academic outcomes in secondary school | 65 |

| 5 | Snowling and Hulme (2020) | Annual Research Review: Reading disorders revisited - the critical importance of oral language | 58 |

| 6 | Carroll et al. (2019) | Literacy interest, home literacy environment and emergent literacy skills in preschoolers | 50 |

| 7 | Catts and Petscher (2021) | A Cumulative Risk and Resilience Model of Dyslexia | 49 |

| 8 | Silinskas et al. (2020b) | The Home Literacy Environment as a Mediator Between Parental Attitudes Toward Shared Reading and Children's Linguistic Competencies | 42 |

| 9 | Niklas et al. (2020) | Home Literacy Activities and Children's Reading Skills, Independent Reading, and Interest in Literacy Activities From Kindergarten to Grade 2 | 42 |

| 10 | S.-Z. Zhang et al. (2024) | How does home literacy environment influence reading comprehension in Chinese? Evidence from a 3-year longitudinal study | 41 |

Table 3 Performance Analysis by Sources

| Rank | Journals | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | Frontiers in Psychology | 23 | 262 | 121 |

| 2 | Early Childhood Research Quarterly | 20 | 251 | 70 |

| 3 | Early Education and Development | 20 | 166 | 58 |

| 4 | Reading and Writing | 18 | 151 | 93 |

| 5 | Journal of Early Childhood Literacy | 18 | 77 | 19 |

| 6 | Early Childhood Education Journal | 12 | 85 | 25 |

| 7 | Journal of Research in Reading | 8 | 69 | 31 |

| 8 | Early Child Development and Care | 7 | 42 | 7 |

| 9 | Education Sciences | 6 | 22 | 24 |

| 10 | Scientific Studies of Reading | 6 | 28 | 20 |

Table 4. Performance Analysis by Authors

| Rank | Authors | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | Torppa, Minna | 11 | 181 | 194 |

| 2 | Inoue, Tomohiro | 10 | 122 | 147 |

| 3 | Lerkkanen, Marja-Kristiina | 9 | 130 | 183 |

| 4 | Georgiou, George K | 8 | 119 | 126 |

| 5 | Niklas, Frank | 7 | 98 | 35 |

| 6 | Wirth, Astrid | 7 | 98 | 35 |

| 7 | Parrila, Rauno | 6 | 77 | 86 |

| 8 | Ma, Minjie | 6 | 12 | 63 |

| 9 | Wang, Qianqian | 6 | 12 | 63 |

| 10 | Wang, Tingzhao | 6 | 12 | 63 |

Table 5. Performance Analysis byOrganisations

| Rank | Organisation | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | Chinese Univ Hong Kong | 15 | 140 | 162 |

| 2 | Univ Jyvaskyla | 14 | 203 | 120 |

| 3 | Univ Hong Kong | 12 | 133 | 68 |

| 4 | Univ Alberta | 10 | 132 | 159 |

| 5 | Univ Cincinati | 10 | 83 | 26 |

| 6 | Univ Houston | 9 | 52 | 31 |

| 7 | Beijing Normal Univ | 8 | 71 | 71 |

| 8 | Univ Stavanger | 8 | 105 | 49 |

| 9 | Univ British Columbia | 8 | 18 | 34 |

| 10 | Purdue Univ | 8 | 89 | 19 |

Table 6. Performance Analysis by Countries

| Rank | Country | Documents | Citations | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | USA | 161 | 1151 | 358 |

| 2 | People R China | 58 | 411 | 395 |

| 3 | Canada | 44 | 434 | 348 |

| 4 | England | 33 | 365 | 191 |

| 5 | Germany | 26 | 349 | 168 |

| 6 | Netherlands | 16 | 147 | 131 |

| 7 | Australia | 15 | 191 | 143 |

| 8 | Norway | 15 | 237 | 140 |

| 9 | Finland | 14 | 203 | 164 |

| 10 | Israel | 14 | 89 | 61 |

Co-Citation Analysis

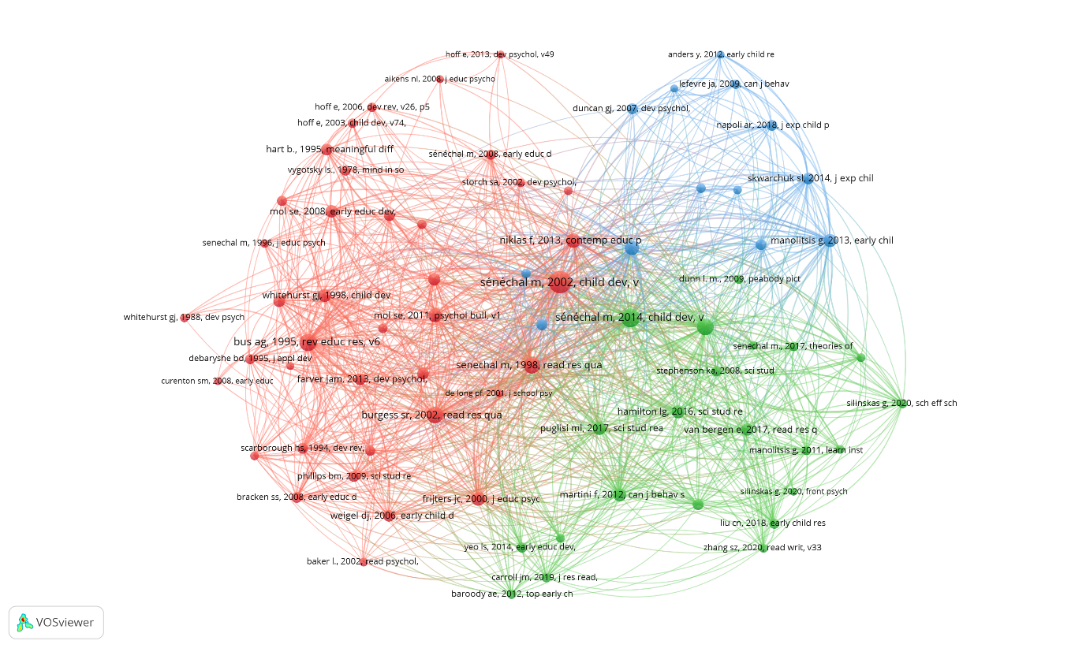

The co-citation analysis data fromVOSviewerin Figure 4 provides a detailed insight into the scholarly influence and interconnectedness of key articles related to home literacy. The data highlights the most influential articles in the domain of home literacy, withSénéchaland LeFevre's works standing out prominently. Their 2002 study, as shown in Table 7, "Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five‐year longitudinal study," is the most co-cited, with 168 citations and a total link strength of 1908. This indicates that their research on parental involvement and its longitudinal effects on children's reading skills is foundational in the field, shaping subsequent studies and theories.

Similarly, their 2014 article, "Continuity and change in the home literacy environment as predictors of growth in vocabulary and reading," with 114 citations and a link strength of 1292, furtheremphasisesthe evolving understanding of the home literacy environment's role over time. The recurrent appearance ofSénéchaland LeFevre’s studies among the top-cited articles suggests that their research provides critical frameworks for understanding the dynamics of home learning, particularly in literacy development. Other notable studies includeS. R.Burgess et al. (2002) examining the impact of the home literacy environment on reading-related abilities. In comparison, Bus et al. (1995) conducted a meta-analysis on intergenerational literacy transmission through joint book reading, which has significantly influenced educational research.

Table 7. Co-citations (Top 10 Articles)

| Rank | Authors | Citations | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | Sénéchal and LeFevre (2002) | 168 | 1908 |

| 2 | Sénéchal and LeFevre (2014) | 114 | 1292 |

| 3 | Sénéchal (2006) | 96 | 1240 |

| 4 | S. R. Burgess et al. (2002) | 91 | 1091 |

| 5 | Sénéchal et al. (1998) | 89 | 1062 |

| 6 | Bus et al. (1995) | 99 | 999 |

| 7 | Hood et al. (2008) | 69 | 971 |

| 8 | Niklas and Schneider (2013) | 73 | 929 |

| 9 | Frijters et al. (2000) | 64 | 771 |

| 10 | Manolitsis et al. (2013) | 58 | 768 |

The cluster analysis in Table 8 further refines our understanding of the research landscape by grouping related studies based on co-citation patterns:

Cluster1 (Red): This cluster, consisting of 39 articles, is heavily influenced bySénéchaland LeFevre’s early works, such as their 2002 and 1998 studies. This cluster emphasizes research investigating the direct impact of home literacy activities and parental involvement on children’s literacy outcomes. It also includes foundational meta-analyses like Bus et al. (1995), which underscore the importance of joint book reading.

Cluster 2 (Green): Comprising 22 articles, this cluster builds on the continuity of literacy practices at home, withSénéchaland LeFevre’s (2014) study leading the group. The research focuses on the persistence of home literacy effects over time and their differential impacts on various literacy skills. It includes studies exploring how home literacy practices evolve and influence children’s development beyond the early years.

Cluster3 (Blue): This smaller cluster of 13 articles includes studies like Hood et al. (2008) andManolitsiset al. (2013), which delve into the specific practices of home literacy and their longitudinal effects. This cluster focuses on preschool and early childhood settings, investigating how early home literacy environments shape future academic outcomes.

Figure 4. Co-CitationAnalysis (VOSviewerVisualization)

The co-citation analysis underscores the centrality of parental involvement and the home literacy environment in the research on home learning. The high citation and link strength of articles bySénéchaland LeFevre suggest that any contemporary study on home learning must consider the foundational frameworks established by these researchers. The clustering of studies indicates that while the field is united in its focus on home literacy, distinct research threads explore different aspects of how home environments contribute to children's educational outcomes.

Table 8. Co-Citation Cluster on Home Literacy

| Cluster No and Colour | Cluster Labels | No. of Articles | Representative Publications |

| Cluster 1 (Red) | Impact of Home Literacy Activities and Parental Involvement | 39 | Sénéchal and LeFevre (2002); Bus et al. (1995); Sénéchal et al. (1998); Niklas and Schneider (2013); Frijters et al. (2000); Whitehurst and Lonigan (1998); Mol and Bus (2011); Phillips and Lonigan (2009); Weigel et al. (2006); Van Steensel (2006) |

| Cluster 2 (Green) | Continuity of Literacy Practices at Home | 22 | Sénéchal and LeFevre (2014); Sénéchal (2006); Hamilton et al. (2016); Martini and Sénéchal (2012); van Bergen et al. (2017); Puglisi et al. (2017); Carroll et al. (2019); Silinskas et al. (2020) |

| Cluster 3 (Blue) | Home Literacy and Longitudinal Effects | 13 | Hood et al. (2008); Manolitsis et al. (2013); Skwarchuk et al. (2014); Duncan et al. (2007); Napoli and Purpura (2018) |

In conclusion, theVOSviewerco-citation analysis provides a clear map of the most influential studies in home learning, emphasizing the significance of parental involvement and the home literacy environment in shaping children's literacy development. This analysis highlights key studies and reveals the thematic clusters that define the research landscape, offering a roadmap for future research in this domain.

Co-Occurrence Analysis Overview

The co-occurrence analysis in Table 9 reveals the frequency and interconnectedness of keywords in the research on home learning, highlighting the primary themes and focal points in this field.

Dominance of "Home Literacy Environment": The term "home literacy environment" is the most frequentlyoccurringkeyword, with 183 mentions and a total link strength of 994. This dominance indicates that a significant body of research focuses on how the home environment influences children's literacy development. The home literacy environment includes factors such as the availability of books, parental reading habits, and the overall encouragement of literacy activities at home.Sénéchaland LeFevre's longitudinal studies emphasize that a rich home literacy environment positively impacts children's reading development and vocabulary growth.

Language and Vocabulary: "Language" (116 occurrences) and "vocabulary" (107 occurrences) are also central keywords, highlighting the emphasis on language acquisition and vocabulary development in home learning research. Studies have shown that children's exposure to language-rich environments at home significantlyboosts their language skills, foundational for later academic success. For instance, Hart and Risley (1995) demonstrated that the quantity and quality of language spoken at home are critical determinants of children's vocabulary growth.

Skills and Emergent Literacy: The prominence of "skills" (108 occurrences) and "emergent literacy" (86 occurrences) points to a focus on the early literacy skills that children develop before they begin formal schooling. These include print awareness, letter knowledge, and phonological awareness, which are critical for successful reading acquisition. Whitehurst and Lonigan (1998) argued that emergent literacy skills developed through home learning activities strongly predict later reading achievement.

Socio-economic Status (SES): "Socio-economic status" (SES) is another frequently mentioned keyword, with 65 occurrences. Research consistently shows that SES impacts the quality and quantity of literacy experiences that children receive at home. For example, Bradley and Corwyn (2002) found that children from higher SES families typically have access to more educational resources, leading to better literacy outcomes. The co-occurrence of SES with home literacy environment and parental involvement underscores the complex interplay between economic factors and educational practices at home.

Preschool and Kindergarten Focus: Keywords like "kindergarten" (68 occurrences) and "preschool-children" (62 occurrences) suggest that much of the research is focused on the early years of education, where foundational literacy skills are developed. This focus aligns with studies like those of Storch and Whitehurst (2002), which found that the skills children acquire in preschool significantly impact their later reading abilities.

Table 9. The 15 Most Frequent Keywords in the Co-Occurrence Analysis

| Rank | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | Home literacy environment | 183 | 994 |

| 2 | Language | 116 | 680 |

| 3 | Skills | 108 | 657 |

| 4 | Vocabulary | 107 | 687 |

| 5 | Home literacy | 106 | 568 |

| 6 | Emergent literacy | 86 | 516 |

| 7 | Children | 81 | 425 |

| 8 | Environment | 71 | 461 |

| 9 | Kindergarten | 68 | 473 |

| 10 | Socioeconomic-status | 65 | 389 |

| 11 | Involvement | 64 | 423 |

| 12 | Preschool-children | 62 | 381 |

| 13 | Phonological awareness | 54 | 330 |

| 14 | Achievement | 54 | 314 |

| 15 | Literacy | 46 | 278 |

Co-Word Analysis

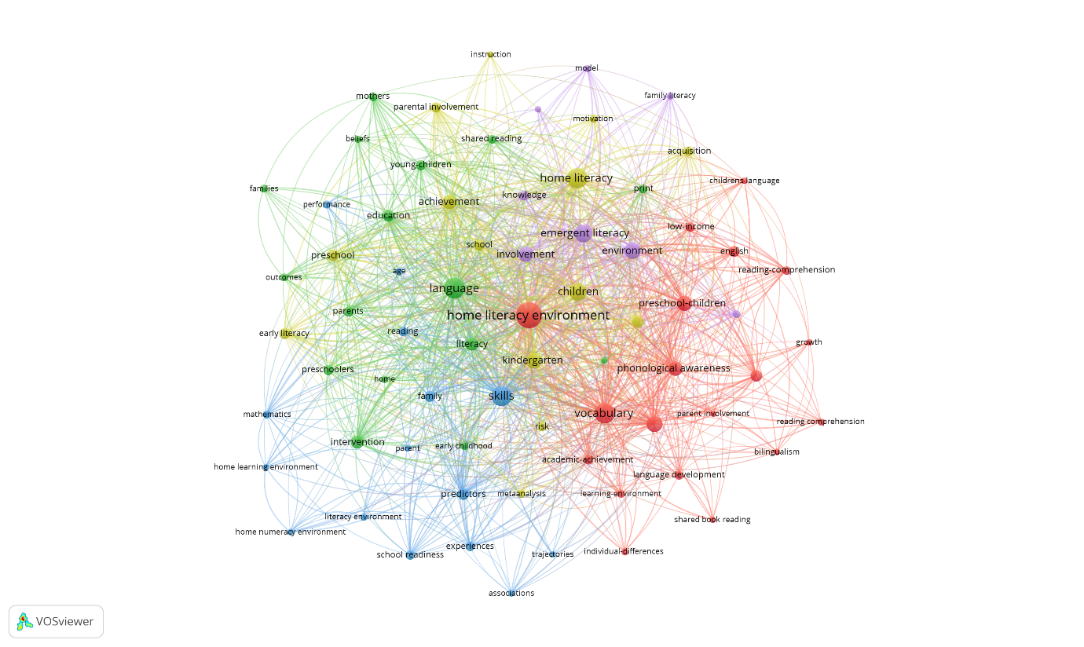

The co-word analysis in Figure 5 groups keywords into clusters, revealing thematic concentrations within the research on home learning. The analysis uncovers five distinct clusters characterized by a specific theme, as seen in Table 10. These clusters represent groups of publications that are interconnected and share a common thematic focus. Below is a description of each cluster along with its corresponding label.

Cluster 1 (Red), Home Literacy and Socio-economic Factors, contains 19 keywords, including "home literacy environment," "vocabulary," and "socio-economic status." The emphasis on these terms suggests a research focus on how the home literacy environment, shaped by factors like SES, affects vocabulary development and other literacy outcomes. Research byS. R.Burgess et al. (2002) found that children from higher SES backgrounds typically have more enriched home literacy environments, leading to stronger vocabulary and reading skills.

Figure 5. Co-Word Analysis of Home Literacy (VOSviewerVisualisation)

Cluster 2 (Green), Language and Literacy Interventions, contains 16 keywords such as "language," "intervention," and "education," which indicate a focus on literacy interventions, particularly in early childhood settings. This cluster likely includes studies on the effectiveness of programs designed to enhance language and literacy skills in young children. For example, Lonigan et al. (2008) reviewed interventions to improve early literacy and found that parent-focused interventions were particularly effective in boosting children's literacy outcomes.

Cluster 3 (Blue), Skills Development and School Readiness, includes 15 keywords, with "skills," "predictors," and "home learning environment" being prominent. The research in this area focuses on how early home learning experiences contribute to developing skills necessary for school readiness. Studies by Duncan et al. (2007) have shown that early math and literacy skills are strong predictors of later academic success, emphasising the importance of home learning environments in preparing children for school.

Cluster 4 (Yellow), Achievement and Motivation, comprises 14 keywords which focus on "achievement," "early literacy," and "motivation." The research here likely explores how home learning influences children's literacy achievement and the motivational factors that drive learning. For instance, Wigfield and Eccles (2000) discussed how children's motivation for learning is shaped by early home experiences, which affects their literacy achievement and academic success.

Cluster 5 (Purple), Emergent Literacy and Family Dynamics, comprises the smallest cluster, with eight keywords,centersaround "emergent literacy," "involvement," and "family literacy." The focus is on how family dynamics, including parental involvement and family literacy practices, contribute to emergent literacy skills. Research by Bus et al. (1995) highlighted the importance of parent-child interactions, such as shared book reading, in promoting emergent literacy.

Table 10. Co-Word Analysis of Home Literacy

| Cluster No and Colour | Cluster Label | Number of Keywords | Representative Keywords |

| 1 (Red) | Home Literacy and Socio-economic Factors | 19 | “home literacy environment,” “vocabulary,” “socio-economic status,” “phonological awareness,” “preschool-children,” “bilingualism,” “growth,” “English,” “individual-differences,” “low-income,” “parent involvement,” “shared book reading” |

| 2 (Green) | Language and Literacy Interventions | 16 | “language,” “intervention,” “education,” “families,” “literacy,” “parents,” “preschoolers,” “shared reading,” “young-children” |

| 3 (Blue) | Skills Development and School Readiness | 15 | “skills,” “predictors,” “family,” “experiences,” “associations,” “home learning environment,” “school readiness,” “performance” |

| 4 (Yellow) | Achievement and Motivation | 14 | “achievement,” “home literacy,” “early literacy,” “children,” “motivation,” “acquisition,” “instruction” |

| 5 (Purple) | Emergent Literacy and Family Dynamics | 8 | “emergent literacy,” “involvement,” “environment,” “model,” “family literacy,” “behavior” |

Conclusion

The co-occurrence and co-word analyses provide a detailed map of the current research landscape in home literacy, highlighting the critical role of the home literacy environment, the impact of socio-economic factors, and the importance of early interventions. The data suggests that future research should continue to explore these themes, particularly in diverse and economically challenged populations. Additionally, the focus on early literacy and the development of language and vocabulary skills underscores the need for targeted interventions that support these foundational aspects of education.

Theoretical Implications

The findings from the bibliometric analysis provide robust theoretical implications for the field of educational research, particularly in the context of early literacy development. The prominence of keywords such as "home literacy environment," "vocabulary," "emergent literacy," and "parental involvement" in the co-occurrence analysis underscores the critical role that the home environment plays in shaping early literacy outcomes (Inoue et al., 2020).

The strong presence of the "home literacy environment" as a central theme in home literacy research aligns closely with Bronfenbrenner's Ecological Systems Theory, which posits that different environmental systems influence human development. As part of the microsystem, the home is the most immediate environment influencing a child's development. This theoryemphasisesthat the family environment, including the availability of literacy resources and the quality of parent-child interactions, directly impacts children's cognitive and literacy development (Niklas et al., 2020). The co-occurrence analysis reinforces the idea that the home is not just a passive setting for learning but an active contributor to literacy development. For example, research has shown that children who grow up in homes with rich literacy environments—where books are readily available and parents regularly engage in literacy activities—tend to have better literacy skills and school readiness (Altun et al.,2022).

Vygotsky's Social Development Theory is also a critical theoretical framework in home literacy. Vygotsky argued that social interaction plays a fundamental role incognitive development, and this is particularly evident in the context of early literacy development. The frequent appearance of keywords such as "parental involvement" and "shared reading" in the co-word analysis suggests that parents are seen as primary educators in the home environment, providing the scaffolding necessary for children to develop literacy skills (Penderiet al., 2023). As highlighted by the analysis, parental involvement is not merely a supportive factor but a critical component of effective home learning. According to Vygotsky, children learn andinternalisenew concepts and skills through guided interactions with more knowledgeable others, often their parents (Meng, 2021).

Another significant theoretical implication of the analysis is the relationship between socio-economic status (SES) and educational attainment. The frequent co-occurrence of SES with keywords related to literacy outcomes suggests that SES remains a powerful determinant of children's literacy development. This relationship is well-documented in the literature, with numerous studies showing that children from higher SES backgrounds have better literacy outcomes due to greater access to educational resources, more enriched home environments, and higher levels of parental involvement (Andersenet al., 2020). The analysis supports the theoretical framework that integrates social and economic factors into models of educational attainment. For instance, the Family Stress Model posits that economic hardship can lead to stress and reduce the quality of the home environment, thereby negatively affecting children's cognitive and emotional development (Bigozziet al., 2023). The bibliometric data reinforces this theory by showing that SES is closely linked with the quality of the home literacy environment and, consequently, literacy outcomes (S.-Z. Zhang et al.,2024).

Emergent Literacy Theory, which posits that literacy development begins long before formal schooling, is also supported by the findings of the co-occurrence and co-word analyses. The frequent mention of "emergent literacy" and "skills" indicates that researchers view early literacy development as a continuous process that starts in infancy and is nurtured by the home environment (Inoue et al., 2020). According to this theory, children's experiences with spoken and written language in the home setting lay the foundation for formal reading and writing instruction later on. The analysis suggests that activities such as reading aloud, storytelling, and engaging in conversations with children are critical in fostering emergent literacy skills such as phonemic awareness, vocabulary development, and print knowledge (Strauss &Bipath, 2021).

Practical Implications

The practical implications of bibliometric analysis are significant for educators, policymakers, and parents. Given the central role of the home literacy environment in shaping literacy outcomes, several actionable steps can be taken to enhance home learning and mitigate the effects of socio-economic disparities.

One of the most direct practical implications is enhancing the home literacy environment for all children, particularly those from low-income families. Research consistently shows that children who have access to books and other literacy materials at home and regularly engage in literacy activities with their parents tend to have better literacy outcomes (Nuswantaraet al., 2022). Therefore, interventions aimed at improving home literacy environments should be a priority. Programs such as Reach Out and Read, which provide books to low-income families and encourage parents to read aloud to their children, effectively enhance home literacy environments and improve children's literacy skills (Mendelsohn et al., 2020). These programs could be expanded and adapted to meet the needs of diverse communities, ensuring that all children have access to the resources and support they need to develop strong literacy skills.

The analysis also underscores the importance of early literacy interventions. The co-word analysis strongly focuses on early childhood, with keywords like "preschool" and "kindergarten" appearing frequently. This suggests that early interventions targeting preschool and kindergarten children are crucial for ensuring school readiness and academic success (Penderiet al., 2023). In addition to formal early childhood education programs, there is also a need for community-based interventions that support literacy development in informal settings. For example, libraries and community centers can play a vital role in providing literacy resources and programs for families, particularly in underserved areas (Sun & Ng, 2021).

Given the strong link between SES and literacy outcomes, addressing socio-economic disparities is a critical practical implication of the analysis. Policymakers should consider strategies to reduce economic inequality and provide targeted support to low-income families. This could include providing financial assistance to families to purchase books and other literacy materials and offering free or low-cost access to early childhood education programs (Bigozziet al., 2023). Furthermore, schools and communities should work together to provide additional support to children from low-income families, such as after-school tutoring programs and summer reading initiatives. These programs can help bridge the gap between children from different socio-economic backgrounds and ensure that all children can develop strong literacy skills (Korosidouet al., 2021).

The analysis also highlights the importance of promoting parental involvement in children's literacy development. Given that parental involvement is a critical component of effective home learning, schools and educators should work to engage parents in their children's education. This could include providing parents with resources and training on how to support their children's literacy development at home and creating opportunities for parents to participate in school-based literacy activities (Chand & Chand, 2025). Programs promoting parent-child interactions around literacy, such as family literacy programs, have effectively improved children's literacy outcomes. These programs typically involve parents and children in literacy activities, helping to strengthen the home literacy environment and enhancing literacy skills (Niklas et al., 2020).

Thus, the bibliometric analysis of home learning highlights the significant impact of the home literacy environment on children's literacy development, with particular emphasis on the roles of parental involvement, socio-economic status, and early intervention. These findings align with the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 4: Quality Education, and SDG 10: Reduced Inequalities, emphasizing the need for inclusive and equitable education opportunities for all children. The results reinforce theoretical frameworks such as Ecological Systems Theory, Social Development Theory, and Emergent Literacy Theory, which suggest that the home is a critical environment for early literacy development.

The analysis suggests that enhancing home literacy environments, providing early literacy interventions, addressing socio-economic disparities, and promoting parental involvement are essential steps in improving literacy outcomes. These efforts not only support SDG 4 by fostering quality education from the early stages but also contribute to SDG 10 by addressing the educational needs of disadvantaged groups. By implementing these strategies, educators, policymakers, and parents can collaborate to create a more equitable and supportive environment for children's literacy development, ensuring that all children have the opportunity to succeed in school and beyond, ultimately contributing to a more inclusive and sustainable future.

Policymakers are urged to develop guidelines that balance the risks and benefits of home literacy,emphasisingthe importance of quality content and parental involvement. These policies should be informed by ongoing research and tailored to meet the needs of diverse cultural and socio-economic contexts. Additionally, educators are encouraged to design interactive activities that foster interaction, learning, and language development, contributing positively to children’s cognitive and socio-emotional growth.

The study’s findings advocate for a balanced and informed approach to a home literacy environment. Moving forward, further research will be essential in refining our understanding of how parental participation in home literacy development affects child growth, guiding the creation of effective interventions to mitigate learning losses. By fostering collaboration among all stakeholders, we can ensure that children’s interactions support their development and prepare them for a future where learning is crucial.

We would like to express our sincere appreciation to the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2023/SSI07/UNISEL/03/1) and the Selangor State Government under the Geran Penyelidikan Negeri Selangor (GPNS Nos. SUK/GPNS/2023/PKS/08).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The authors would like to thank INTI International University for its continuous support of academic research and publication funding.

No ethical approval was sought as the article does not present any study of human or animal subjects.

Data sharing is not applicable as no new data was created or analyzed in the presented study.

Generative AI Statement

The author has not used generative AI or AI-supported technologies.

AuthorshipContributionStatement

Pek: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data; Wrote the paper.Mee: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data; Wrote the paper.Nallisamy: Proofread and formatted the paper to match the journal requirements.Yob: Performed the Analysis usingVOSviewerand worked on the formatting. Miftah: Analyzed and interpreted the data. Elfi: Analyzed and interpreted the data.