Introduction

In education, emotions are central to the relationships teachers build with students, families, and the wider learning community (Frenzel et al., 2021; Stark & Cummings, 2023). For early childhood educators (ECE), nurturing close emotional ties is essential for fostering young children’s social-emotional development (Curby et al.,2022; Hatton-Bowers et al., 2023). Within this context, emotional labor refers to the deliberate management of feelings and emotional expressions to meet professional role expectations (Hochschild, 1983). Although emotional labor can sustain positive classroom climates, mounting evidence indicates that continual suppression or surface acting may erode teachers’ psychological well-being and increase the risk of burnout (Chang, 2020; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017).

Despite a growing body of international research, three critical lacunae persist. Primary attention has been devoted to primary- and secondary-level teachers; the distinctive emotional burden confronting early childhood educators—who concurrently fulfill caregiver, pedagogue, and family-liaison roles—remains sufficiently explored (Purper et al., 2023). Second, empirical evidence specific to collectivist contexts such as Indonesia is scarce. Existing studies (Novianti, 2018; Ramadhanti et al., 2023) describe broad cultural norms favouring harmony, yet provide little insight into how these norms shape daily emotional regulation strategies among ECE teachers. Third, prior investigations have rarely differentiated emotional labor directed at children versus parents, preventing a nuanced understanding of interpersonal sources of strain.

In collectivist cultures like Indonesia, where community and harmony are highly valued, teachers may experience an even greater emotional burden(Hofstede, 2001a; Triandis, 1995). These cultural values add another layer to how emotional responsibilities play out in schools, particularly in the context of school-parent cooperation. Gokalp et al. (2021) highlight communication barriers that can arise in such interactions, further complicating the emotional labor experienced by teachers. Additionally, Yasar and Demir (2015)have shown that emotional labor can lead to increased levels of depression and burnout among teachers, emphasizing the need for a deeper understanding of the emotional burden placed on educators in different cultural contexts.

To address these gaps, the present study poses the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the relative intensity of emotion suppression and surface acting experienced by Indonesian ECE teachers in interactions with (a) children and (b) parents?

RQ2: To what extent do demographic characteristics (generation, teaching experience, education level, salary, certification) and emotional labor dimensions predict teachers’ emotional well-being?

Based on the Job Demands–Resources model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) and cross-cultural emotional labor research (Grandey et al., 2013), we hypothesize that (H1) emotion suppression will be more prevalent than surface acting, especially in parent interactions; and (H2) higher levels of emotion suppression will negatively predict emotional well-being.

Literature Review

In early childhood classrooms, emotions are at the heart of every interaction. Teachers not only guide children’s learning but also help shape how young minds understand and express feelings. This emotional work, often described as emotional labor, involves managing one’s own emotions and expressions to meet professional expectations (Gabriel et al., 2023; Hochschild, 1983).

For early childhood educators, emotional labor is more than just maintaining a pleasant tone—it’s part of building safe, supportive environments where children feel secure. Several strategies come into play here, including surface acting (displaying a smile even in challenging circumstances), deep acting (attempting to genuinely feel the expected emotions), suppressing unwanted emotions, and expressing emotions that are authentic (Farah, 2023; Lee & Madera, 2019). These strategies affect teachers in different ways. While deep acting and authenticity can support positive relationships and job satisfaction (Alabak et al., 2020; Humphrey et al., 2015), surface acting and suppression are often linked to emotional fatigue and burnout (Brotheridge & Lee, 2003; Grandey et al., 2013).

In Indonesia, cultural expectations add another layer of complexity. As a collectivist society, there’s a strong emphasis on maintaining group harmony and emotional balance, even when it means putting personal feelings aside (Novianti, 2018; Ramadhanti et al., 2023). For early childhood educators, emotional expression is not merely a professional expectation—it is often intertwined with how society perceives their role. These teachers are frequently regarded as warm, nurturing figures who provide care that echoes the support children receive at home (Pratiwi et al., 2023; Souto-Manning & Mitchell, 2010). In practice, this perception can translate into a continuous expectation to remain calm, patient, and emotionally available, regardless of the internal pressures they may be experiencing.

Such emotional burden rarely occurs in isolation. Teachers must navigate a range of external challenges, including limited institutional support, high expectations from families, and financial constraints. These systemic issues often exacerbate the emotional burden associated with the role. Teachers bring their own life stories into the classroom, and aspects such as age, teaching experience, and upbringing can influence the way they respond to emotional burden (García-Arroyo et al., 2019).

In this context, emotional intelligence becomes a valuable asset. It equips educators with the capacity to recognize, regulate, and respond to emotions—both their own and those of others—in a way that maintains the emotional safety of the classroom (Pekrun, 2021; Samnøy et al., 2023). As the emotional landscape of early education becomes more complex, these skills are becoming increasingly essential for fostering a positive and stable learning environment.

This research explores how Indonesian early childhood teachers navigate the emotional aspects of their daily interactions with young learners and their families, and how these experiences shape their sense of well-being. Rather than merely measuring how often teachers regulate their emotions, the research considers how these efforts shape their overall well-being. By bringing attention to these lived experiences, the study aims to inform more responsive and culturally grounded support systems—ones that recognize emotional labor as a fundamental part of teaching and provide meaningful strategies to help educators thrive in their roles.

Methodology

ResearchDesign

This study employed a quantitative approach with a descriptive-correlational design to examine the relationship between emotional labor and various demographic and professional factors among ECE teachers. This method enabled the analysis of measurable patterns within systematically collected data. The approach was chosen to identify trends across a large sample, offering insights that can inform teacher training, emotional support strategies, and policy development in early childhood education.

Variables and Participants

The dependent variables in this study are the emotional labor dimensions measured by the Teacher Emotional Labor Toward Students (TEL-S) scales. These dimensions include Surface Acting and Emotion Suppression, which are hypothesized to be associated with various demographic characteristics of the teachers and to predict their work satisfaction and performance. To prepare the data for regression analysis, each variable was coded according to specific schemes. The detailed coding schemes for all variables used in the regression analysis are presented in Table 1.

From an initial pool of 500 invited educators, 397 Indonesian early-childhood teachers(with at least one year of teaching experience and who provided voluntary consent) were recruited via purposive sampling (Elvira et al., 2023). Underpinned by Hofstede’s (2001b) collectivism framework, the purposive approach secured cultural coherence and, in line with the JD-R model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), enhanced construct validity for this occupational cohort. Although non-random, its pragmatic design is justified under resource constraints; detailed demographics appear in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Profile and Operational Coding of Study Variables

| Variable | Operational Definition | Scale and Categories Code | Freq. | Percent. (%) |

| Gender | Identification of the respondent's gender. | Nominal | ||

| 0 = Female | 372 | 93.7 | ||

| 1 = Male | 25 | 6.3 | ||

| Age | Age group of the respondent, categorized by generational cohorts. | Ordinal | ||

| 1 = ≤28 (Z Gen 1997-2012) | 103 | 25.94 | ||

| 2 = 29–44 (Milenial Gen 1981-1996) | 187 | 47.1 | ||

| 3 = 45–60 (X Gen 1965-1980) | 104 | 26.2 | ||

| 4 = ≥61 (Boomers Gen <1965) | 3 | 0.76 | ||

| Teaching Experience | Years of teaching experience. | Ordinal | ||

| 1 = < 2 years | 46 | 11.59 | ||

| 2 = 2-5 years | 91 | 22.92 | ||

| 3 = 5-10 years | 92 | 23.17 | ||

| 4 = > 10 years | 168 | 42.32 | ||

| Education Level | Highest level of education attained. | Ordinal | ||

| 1 = High School | 77 | 19.4 | ||

| 2 = Diploma | 4 | 1.01 | ||

| 3 = Bachelor's Degree | 39 | 9.82 | ||

| 4 = Bachelor's Degree in Education | 58 | 14.61 | ||

| 5 = Bachelor's Degree in Early Childhood Education | 138 | 34.76 | ||

| 6 = Master's Degree | 11 | 2.77 | ||

| Monthly Salary Range | Monthly salary range of the respondent. | Ordinal | ||

| 1 = Rp 0 - 500,000 | 222 | 55.92 | ||

| 2 = Rp 500,001 - 1,000,000 | 113 | 28.46 | ||

| 3 = Rp 1,000,001 - 2,000,000 | 29 | 7.3 | ||

| 4 = Rp 2,000,001 - 3,000,000 | 24 | 6.05 | ||

| 5 = Rp 3,000,001 - 5,000,000 | 8 | 2.02 | ||

| Teaching Certificate | Whether the respondent possesses a teaching certificate. | Nominal | ||

| 1 = No | 203 | 51.13 | ||

| 2 = Yes | 194 | 48.87 | ||

| Teacher Emotional labor toward Students (TEL-S) | Emotional labor exhibited by teachers toward students. | Ordinal | ||

| 1 = Extremely Burdened | 77 | 19.40 | ||

| 2 = Burdened | 94 | 23.68 | ||

| 3 = Moderately Burdened | 132 | 33.25 | ||

| 4 = Slightly Burdened | 57 | 14.36 | ||

| 5 = Not Burdened at All | 37 | 9.32 | ||

| Teacher Emotional Labor Toward Parents (TEL-P) | Emotional labor exhibited by teachers toward parents. | Ordinal | ||

| 1 = Extremely Burdened | 82 | 20.65 | ||

| 2 = Burdened | 128 | 32.24 | ||

| 3 = Moderately Burdened | 139 | 35.01 | ||

| 4 = Slightly Burdened | 36 | 9.07 | ||

| 5 = Not Burdened at All | 12 | 3.02 |

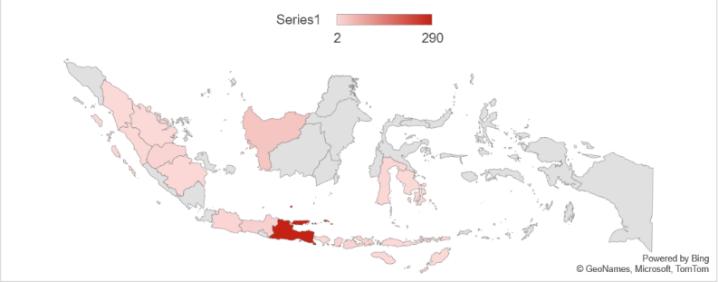

The spatial distribution of the study participants was depicted through a choropleth map (Figure 1), wherein deeper hues represented regions with elevated respondent densities.

Figure 1. Geographic Distribution of Respondents

The respondents constitute a representative sample of Indonesian early-childhood educators whose demographic configuration both mirrors the sector’s structure and foreshadows region-specific emotional challenges. Gender: 93.7% are female, evidencing the pronounced gender imbalance in Indonesian ECE and amplifying emotional pressure through the dual roles frequently attached to female educators (Hofstede, 2001b). Geographic distribution: 73% are located in East Java, underscoring the concentration of the educator workforce in this province. Meanwhile, West Java, NTB, Sulawesi, Kalimantan, Jambi, and Bali collectively account for the remainder. In Hofstede’s (2001b)collectivistic culture framework, densely populated regions are characterized by stricter harmony norms, which heighten emotional display demands on educators.

Age cohorts :The largest group (47.1%) falls within the 29–44-year-old range (Millennials), a career stage typically associated with peak professional responsibility, followed by Gen X (26.2%). Only 0.76% are aged 61 years or older (Boomers), indicating minimal participation.

Teaching experience: 42.3 % have > 10 years of service—a cohort that, per the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), generally possesses mature emotion-regulation strategies—yet 11.6 % have < 2 years, thereby facing elevated emotional-load risk. Educational attainment: Bachelor’s degrees in Early Childhood Education (34.8%) dominate, whereas 19.4% hold only high school qualifications, revealing qualification heterogeneity that may influence regulatory quality.

Monthly salary: 55.9 % earn ≤ Rp 500,000; such limited financial resources constitute a depleted external resource that, according to JD-R, intensifies emotional burden. Teaching certification: only 48.9 % possess a formal teaching certificate, leaving nearly half without the protective training that mitigates burnout risk. Consequently, the respondent profile—predominantly female, Millennial, East-Javanese, low-paid, and variably certified—constitutes a unique context in which demographic variables must be integrated into predictive models of teacher emotional labor in Indonesian ECE.

Data Collection

The methodology for data collection encompassed multiple phases: the formulation of the questionnaire, its online dissemination, and the oversight of the amassed responses. The survey was conducted using Google Forms, which provided extensive accessibility to participants nationwide (Sainuddin et al., 2022). Before filling out the questionnaire, participants were clearly informed about the study's purpose and provided their informed consent willingly.

The stages of data collection included:

Instrument Preparation –Survey instruments were meticulously constructed and evaluated to guarantee clarity and pertinence.

Distribution –Questionnaires were disseminated through electronic mail and on social media platforms commonly utilized by early childhood education professionals.

Data Handling –All responses were securely stored in encrypted files to protect participant privacy and confidentiality.

Instrument Development and Validation

Data were collected using two main instruments: the Teacher Emotional Labor toward Students (TEL-S) and the Parent–Teacher Emotional Labor (TEL-P) scales. Both tools were adapted to fit the Indonesian educational and cultural context. TEL-S focused on teacher interactions with students, while TEL-P measured emotional labor in dealings with parents. Each scale assessed two main dimensions:

Surface Acting–the extent to which teachers display emotions inconsistent with their internal states.

Emotion Suppression–the capacity to withhold or restrain emotional expressions in professional settings.

Both instruments used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from "strongly disagree" to "strongly agree."

Table 2. Emotional Labor Instrument Blueprint

| Variable | Indicator | Item Numbers | Total Items |

| Teachers Emotional labor toward Students (TEL-S) | Surface Acting (TSA-S) | 01, 02, 03 | 3 |

| Emotion Suppression (TES-S) | 04, 05, 06, 07 | 4 | |

| Subtotal | 7 | ||

| Teachers Emotional Labor Toward Parents (TEL-P) | Surface Acting (TSA-P) | 17, 18, 19 | 3 |

| Emotion Suppression (TES-P) | 20, 21, 22, 23 | 4 | |

| Subtotal | 7 | ||

| Total | 14 |

Data were collected with the 14-item Teacher Emotional Labor toward Students (TEL-S) and Parent–Teacher Emotional Labor(TEL-P) scales. Each instrument contains two dimensions measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree): Surface Acting (displaying emotions incongruent with inner feelings) and Emotion Suppression (withholding or restraining emotional expression). Table 2 presents the item allocation: TEL-S comprises three Surface-Acting items (01–03) and four Emotion-Suppression items (04–07); TEL-P mirrors this structure with items 17–19 and 20–23, respectively, yielding seven items per scale anda total of14 items overall. The instruments were culturally adapted through translation, expert review, and pilot testing to ensure linguistic and contextual relevance for Indonesian ECE teachers.

For the main study (N = 397), the questionnaire was disseminated via Google Forms through ECE professional networks after securing informed consent; all responses were encrypted and anonymized. Reliability analyses yielded Cronbach’s α = .723 and ordinal α = .771 for TEL-S, and α = .678 and ordinal α = .739 for TEL-P; composite reliability reached .85 and .82, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis produced acceptable fit indices and all standardized factor loadings ≥ 0.546 (p <.001; see Table 3), confirming the two-factor structure for both scales. Thus, the adapted TEL-S and TEL-P are linguistically, culturally, and psychometrically validated instruments for Indonesian early-childhood educators.

Table 3. Factor Loadings for Emotional Labor Dimensions

| Latent | Observed | Estimate | Standard Estimate (factor loadings) | z | p |

| TEL_S | SSA01 | 1.000 | 0.664 | ||

| SSA02 | 0.973 | 0.646 | 14.4 | < .001 | |

| SSA03 | 0.895 | 0.594 | 14.8 | < .001 | |

| SES01 | 0.847 | 0.562 | 14.6 | < .001 | |

| SES02 | 0.91 | 0.604 | 14.9 | < .001 | |

| SES03 | 0.969 | 0.643 | 15.9 | < .001 | |

| SES04 | 0.923 | 0.613 | 15.6 | < .001 | |

| TEL_P | PSA01 | 1.000 | 0.546 | ||

| PSA02 | 1.041 | 0.568 | 12.8 | < .001 | |

| PSA03 | 1.091 | 0.596 | 12.7 | < .001 | |

| PES01 | 1.215 | 0.663 | 13.8 | < .001 | |

| PES02 | 1.112 | 0.608 | 13.6 | < .001 | |

| PES03 | 1.136 | 0.62 | 13.8 | < .001 | |

| PES04 | 1.131 | 0.618 | 13.9 | < .001 |

Data Collection

Data collection was carried out online using Google Forms. From 500 distributed questionnaires, 397 valid responses were obtained. Respondents were provided with clear instructions and information regarding the study's aims and confidentiality practices. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

DataAnalysis

Data were analyzed using JAMOVI and Microsoft Excel. The analysis included:

Descriptive Statistics– to describe participant characteristics and summarize emotional labor scores.

Inferential Statistics–including regression analysis to assess the relationships between demographic/professional variables and emotional labor dimensions.

Regression Assumptions Check

Normality of Residuals: The Shapiro-Wilk test indicates slight deviation from normality (p =.021). However, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (p =.589) and Anderson-Darling test (p =.054) do not indicate significant violations of normality assumptions.

Heteroscedasticity: Results from the Breusch-Pagan (p =.669), Goldfeld-Quandt (p =.865), and Harrison-McCabe (p =.878) tests indicate that residual variance remains constant, supporting the validity of the regression model.

Autocorrelation of Residuals: The Durbin-Watson test (DW =1.98,p =.824) indicates no autocorrelation in the residuals, suggesting that the prediction errors in the model are independent.

Multicollinearity: The VIF statistics for all variables are below the 10 threshold, and tolerance values are above .5, indicating no significant multicollinearity issues in the model.

Findings/Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for Emotional Labor Dimensions

| Descriptive Statistics | TEL-S | TEL-P |

| Mean | 2.33 | 2.17 |

| Median | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Mode | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.10 | 1.05 |

| Minimum | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Maximum | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Range | 3.00 | 3.00 |

| Variance | 1.21 | 1.11 |

Table 4 summarizes the descriptive statistics for TEL-S and TEL-P, showing moderate levels of emotional labor overall, with slightly less variability in parent interactions.

Distribution of Teacher Emotional Labor

Table 5. Distribution of Teacher Emotional Labor toward Students (TEL-S)

| Category | TEL-S | TSA-S | TES-S |

| Not Burdened at All | 9% | 29% | 8% |

| Slightly Burdened | 14% | 14% | 11% |

| Moderately Burdened | 33% | 21% | 17% |

| Burdened | 24% | 13% | 26% |

| Extremely Burdened | 19% | 23% | 38% |

Table 6. Distribution of Teacher Emotional Labor Toward Parents (TEL-P)

| Category | TEL-P | TSA-P | TES-P |

| Not Burdened at All | 3% | 29% | 2% |

| Slightly Burdened | 9% | 17% | 3% |

| Moderately Burdened | 35% | 23% | 9% |

| Burdened | 32% | 14% | 33% |

| Extremely Burdened | 21% | 17% | 53% |

Tables 5 and 6 show that emotion suppression toward parents has the highest proportion of 'extremely burdened' responses, while surface acting tends to be less burdensome.

For instance, surface acting (TSA-S)reveals a higher proportion of teachers (29%) who reportno emotional burden at all, suggesting that some teachers may find it relatively manageable to adopt outward emotional displays in the classroom. In contrast, Emotion Suppression (TES-S) appears to pose a more significant challenge, with 38% of respondents identifying as extremely burdened—the highest proportion in that category.

This contrast highlights how different emotion regulation strategies impact teachers in unique ways. While surface acting may be more tolerable or perhaps even normalized in some educational settings, the intensity of suppressing genuine emotions can take a greater psychological toll.

Inferential Analysis

Table 7. Model Fit Measures

| Model | R | R² | Adj. R² | F | df1 | df2 | p |

| 1 | 0.432 | 0.187 | 0.174 | 14.9 | 6 | 390 | < .001 |

Table 7 presents the model fit measures for the linear regression analysis. While the model's contribution to the variance in the dependent variable is relatively modest (R² = .187), it remains statistically significant (p <.001). This indicates that, despite explaining only a small proportion of the variance, the model provides meaningful insights into the relationships among the variables analyzed.

Table 8. Model Coefficients

| Predictor | Estimate | SE | t | p | Std. Estimate |

| Intercept | 1.1827 | 0.2382 | 4.966 | < .001 | - |

| Generation | 0.1197 | 0.1006 | 1.190 | .235 | 0.0740 |

| Teaching Experience | -0.0714 | 0.0735 | -0.972 | .332 | -0.0628 |

| Education Level | 0.1249 | 0.0375 | 3.327 | < .001 | 0.1646 |

| Salary Range | -0.0367 | 0.0600 | -0.611 | .541 | -0.0300 |

| Teaching Certification | -0.1451 | 0.1218 | -1.191 | .234 | -0.0604 |

| TEL-P | 0.4811 | 0.0549 | 8.764 | < .001 | 0.4044 |

Table 8 shows the coefficients of the regression model, highlighting the relationships between the predictors and the dependent variable. Among all predictors analyzed, Teacher Emotional labor toward Parents (TEL-P) exhibits the strongest impact, as reflected in its high standardized coefficient (0.4044) and strong statistical significance (p <.001). This suggests that TEL-P is a key determinant of variations in the dependent variable. Additionally, Education Level shows a significant positive relationship (p <.001, standardized coefficient = 0.1646), indicating that higher educational attainment is correlated with improved outcomes in the dependent variable.

Conversely, Generation, Teaching Experience, Salary Range, and Teaching Certification do not demonstrate significant effects, as indicated by their high p-values and relatively small standardized coefficients. This suggests that other dominant factors might better explain the variability in the dependent variable or that the measurement of these predictors does not fully capture their potential influence.

Table 9. Correlation Matrix

| Variables | TEL-S | Gen | TE | EL | SR | TC | TEL-P |

| TEL-S | — | ||||||

| Generation (Gen) | .071 | — | |||||

| Teaching Experience (TE) | .025 | .656*** | — | ||||

| Education Level (EL) | .121* | .092 | .273*** | — | |||

| Salary Range (SR) | .014 | .201*** | .220*** | .276*** | — | ||

| Teaching Certification (TC) | -.038 | .356*** | .385*** | .067 | .225*** | — | |

| TEL-P | .398*** | .125* | .06 | -.052 | .026 | .038 | — |

Note. *p <.05, **p <.01, ***p <.001

Table 9 presents the correlation matrix for all variables, providing a clearer picture of the relationships between variables. The asterisks (*) denote statistically significant correlations at the 0.05 level, indicating that some variables are moderately related. For instance, TEL-S has a significant positive correlation with Education Level (0.121) and Teaching Certification (0.038), suggesting that teachers with higher education and certification might experience different levels of emotional labor toward students. Similarly, TEL-P is significantly correlated with Education Level (0.1646), indicating that higher educational attainment might be associated with different emotional labor experiences in interactions with parents.

Discussion

The present findings are best understood when read through three mutually reinforcing theoretical lenses introduced earlier: the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), Emotional Labor Theory (Grandey et al., 2013), and research on collectivistic display rules (Hofstede, 2001a). From a JD-R perspective, emotion suppression toward parents functions as a chronic job demand that erodes the finite self-regulatory resources of early childhood educators. The regression coefficient for Teacher Emotional labor toward Parents (β = 0.404,p <.001) indicates that a one-standard-deviation increase in suppression burden corresponds to a 0.404-standard-deviation decrease in emotional well-being—an effect size Cohen (1992) classifies as medium-to-large. Translated into the 5-point well-being scale used in this study, this β translates into an expected shift of roughly 0.4 scale points—large enough to move a teacher from “quite satisfied” to “somewhat dissatisfied,” a difference that interviewees themselves describe as meaningful in daily practice.

At the same time, education level exerts a modest protective effect (β = 0.165, p <.001). Rather than implying that schooling directly lowers emotional burden, this result is more plausibly interpreted through JD-R as a resource paradox: advanced qualifications raise institutional expectations (higher demands) yet simultaneously furnish cognitive reappraisal skills, social legitimacy, and access to professional networks (augmented resources). The net outcome remains positive for well-being, but the pathway is nuanced and warrants longitudinal examination.

Emotional labor Theory clarifies why suppression is more depleting than surface acting. Suppression requires continuous self-monitoring to inhibit genuine affect, consuming limited regulatory resources without offering any expressive “shield” to the outside world. Surface acting, by contrast, allows the teacher to display socially expected emotions while keeping inner feelings private; although not cost-free, the strategy is less psychologically invasive. Descriptive findings reinforce this theoretical distinction: 53% of respondents report feeling “extremely burdened” by suppression during parent interactions, whereas only 29 % report “no burden at all” from surface acting. The asymmetry underlines the theoretical contention that suppression is the more toxic component of emotional labor (Brotheridge & Lee, 2003).

Collectivistic display-rule research further illuminates why suppression is especially pronounced in parent-directed interactions. Indonesian society values harmony and respect for elders; parents are not merely clients but community stakeholders whose opinions significantly influence a teacher’s reputation (Triandis, 1995). Although cross-cultural comparisons remain scarce, a meta-analysis across 36 societies by García-Arroyo et al. (2019) suggests that collectivistic cultures tend to amplify the strain of emotion suppression, supporting the pattern observed here.

Importantly, the modest predictive power of the regression model (R² = 18.7 %) is explicitly acknowledged. While statistically significant, the model captures only a modestportion of the phenomenon, indicating that unmeasured variables—such as principal support, emotional intelligence, workload intensity, and community socioeconomicstatus—likely account for the remaining variance (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017). Moreover, the sample is restricted to currently practicing teachers; individuals who have exited the profession due to emotional overload are excluded, which attenuates the observed relationships. Future mixed-methods and longitudinal designs are needed to test causal pathways and capture the dynamic fluctuations in emotional labor that occur throughout the school year.

The positive, albeit small, effect of education level warrants closer scrutiny. Rather than speculating, we offer three empirically grounded hypotheses drawn from the literature. First, resource augmentation: advanced teacher-education programs in Indonesia now embed emotional-intelligence modules that enhance cognitive reappraisal skills (Brackett et al., 2011). Second, selection effects: individuals who persist through higher education may possess pre-existing dispositional resilience. Third, role expansion: better-educated teachers are often appointed to curriculum leadership positions, increasing both the emotional burden and the status-based resources. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive; qualitative follow-up could illuminate which pathway dominates. Collectively, these results underscore the need to transcend generic prescriptions and to implement context-sensitive, partnership-based initiatives that acknowledge educators as integral members of culturally bound communities.

Conclusion

This correlational study demonstrates that parent-directed emotion suppression is the strongest predictor of reduced emotional well-being among Indonesian early childhood educators (β = 0.404). Education level offers a modest buffer (β = 0.165), likely via enriched coping resources rather than lighter demands. Collectivistic norms intensify expectations of suppression, especially during parent-child interactions. These findings refine JD-R applications in collectivist settings and foreground suppression as a culturally scripted risk factor. Practically, suppression-management workshops co-designed with parents and peer-reflective professional learning communities are warranted, but their causal efficacy awaits longitudinal evaluation.

Recommendations

For researchers: Future investigations should adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to test the causal pathways implied by the present correlational evidence. Mixed-methods studies that combine physiological stress indicators with ethnographic classroom observations are needed to illuminate the micro-processes through which emotion suppression unfolds during parent–teacher interactions. Expanding the predictor set to include principal support, emotional intelligence, and community-level socioeconomic stressors is likely to increase the currently modest explanatory power of the model (R² = 18.7%) and refine predictive accuracy.

For practitioners and policymakers: First, co-design brief suppression-management modules collaboratively with parents and teachers; Early pilot work in two East-Javanese districts suggests a measurable reduction in self-reported suppression burden; formal evaluation is required. Second, allocate protected time for monthly peer-reflective professional learning communities in which educators rehearse culturally consonant scripts for challenging conversations. Third, embed explicit emotional labour literacy within pre-service teacher education curricula to ensure that graduates possess adaptive regulation strategies prior to entering classrooms. Each recommendation is explicitly linked to the finding that parent-directed emotion suppression is the strongest correlate of diminished well-being.

Limitations

In addition to cultural specificity, three methodological constraints merit explicit acknowledgment. First, reliance on self-report instruments entails the risk of social desirability bias; future studies should incorporate multi-source ratings from principals or parents to triangulate emotional labor experiences. Second, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference; subsequent waves should capture seasonal fluctuations in parent-meeting intensity. Third, the present model omits emotional intelligence and institutional support, variables that have been previously demonstrated to moderate strain within the JD-R framework.

Ethics Statements

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the relevant institutional ethics committee, ensuring compliance with established ethical guidelines for social science research. Participants were fully informed of the study's objectives, procedures, and their right to voluntary participation. They were assured that their involvement was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw at any stage of the research without any negative consequences. All data collected was anonymized and used solely for academic purposes, ensuring confidentiality and the protection of participants' identities..

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to Universitas Islam Negeri Maulana Malik Ibrahim Malang for its invaluable institutional support, which was essential in facilitating the successful completion of this research. Special thanks are extended to the early childhood educators who participated in this study. Their openness, insights, and willingness to contribute were crucial in enriching the data and guiding the direction of this work. The author would also like to acknowledge their colleagues and mentors for their constructive feedback and encouragement throughout the research process. Their guidance has been greatly appreciated.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Generative AI Statement

As the authors of this work, we utilized the AI tool ChatGPT to translate the manuscript from its original Indonesian version into English. After using this AI tool, we reviewed and verified the final version of our work. We, as the authors, take full responsibility for the content of our published work.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Mukhlis: Conceptualization, design, data analysis/interpretation, drafting manuscript, final approval. Elvira: Conceptualization, design, writing, critical revision of manuscript, supervision, final approval. Santoso: Data acquisition, analysis, drafting manuscript,andcritical revision of manuscript. Sainuddin: Statistical analysis, data interpretation, critical revision of manuscript, supervision, and final approval.