Introduction

In the Indonesian higher education landscape, faculty turnover remains a serious concern due to its impact on academic continuity, institutional reputation, and long-term development. A recent report from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology of the Republic of Indonesia stated that some public and private universities have annual faculty turnover rates of 8% to 15% due to early retirements, contract-based job uncertainty, and lack of career progression(Banata et al., 2023). Similarly, a global study estimates that faculty turnover rates in developing countries are approximately 21% (Rahman et al., 2025). Certainly, these statistics underscore the urgent need to enhance faculty retention in Indonesia, particularly in light of the growing demand for educators to meet the increasing number of higher education institutions and enrolled students.

Despite the implementation of various human resource initiatives, many universities continue to face challenges in maintaining faculty stability, which in turn impacts their competitiveness and quality assurance. This highlights the need to study the more deeply rooted, internal psychological drivers of the faculty’s intention to stay, which have been little studied in the Indonesian context(Kristanti et al., 2021).

While research from a more global perspective has focused on external factors, such as compensation, workload, or organizational policies, to explain turnover, relatively few studies have explored intrinsic factors, including workplace spirituality (WPS) or person-organization fit (POF). These factors reflect the convergence of personal principles with an organization’s culture as well as the purpose and connection employees feel toward their workplace.Due to the value-driven nature of academic professions, it is particularly crucial for educational institutions to examine these internal factors.

Faculty turnover results in more than just administrative concerns. Losing experienced faculty members results in the loss of institutional memory, disruption of the learning process, and increased costs associated with recruitment and training. Such losses, particularly in Indonesia, where there is a shortage of faculty, can significantly hinder an institution’s ability to meet national standards and achieve accreditation. Little is known about the psychological and relational factors that contribute to faculty retention.

Workplace spirituality refers to the integration of meaning, purpose, community, shared values, or culture within an organization, which can strengthen organizational commitment while reducing turnover(Charoensukmongkol et al., 2016). Along the same lines, when faculties experience high alignment (fit)between their personal values and the university's mission, they tend to stay engaged and committed to their work. According to social exchange theory, alignment cannot be created without mutual trust, which forms strong emotional bonds to the organization and its members. While existing studies have documented a positive relationship between POF and WPS, with outcomes such as job satisfaction and organizational commitment (Ghadi, 2017; Milliman et al., 2018), the indirect pathways through which they impact turnover, particularly through engagement, remain understudied. In addition, the academic environment in Indonesia presents an interesting context for studying these relationships, given the normative and value-driven expectations of faculty members.

This research aims to bridge the gap by examining the impact of WPS and POF on the turnover intentions of Indonesian faculty members, with employee engagement serving as a mediating factor. Thus, the research seeks to make a new contribution by emphasizing workplace effectiveness and sustainability in a competitive academic setting. To describe the problem in a more structured manner, this research draws on two guiding theories: the Social Exchange Theory (SET) and the Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory. According to SET, employees form reciprocal exchanges with their organizations, either staying or leaving based on their perception of the organization’s support and value alignment. On the other hand, COR theory elaborates on how people aim to protect their valuable psychological and emotional resources, such as purpose, fit, and engagement, which tend to be strained when there is misalignment with the organization. This research aims to investigate how intangible and workplace attributes influence turnover intentions among academic staff in Indonesia, drawing on these theories.

Literature Review

Workplace Spirituality (WPS)

Workplace Spirituality refers to employees' experience of meaningful work within a value-driven organizational setting that nurtures their inner growth and emotional well-being(Ashmos & Duchon, 2000; Vasconcelos,2023). Rather than being tied to religion, WPS involves the pursuit of purpose, ethical behavior, and connection with others at work(Singh & Singh, 2022). Most scholars identify three primary dimensions of WPS: a) meaningful work, employees feel that their tasks have a deeper purpose; b) a sense of community, relationships in the workplace are supportive and respectful; and c) value alignment, personal and organizational values are perceived as congruent(Milliman et al., 2018; Petchsawang & McLean, 2017). These dimensions contribute to greater satisfaction, engagement, and emotional attachment to the organization. Numerous studies have demonstrated that WPS yields various positive outcomes, including reduced turnover intention (Beehner & Blackwell, 2016), enhanced mental well-being (Jnaneswar & Sulphey, 2023), stronger job commitment (Saks, 2011), and higher organizational performance (Sharma & Singh, 2021). Due to these benefits, WPS has emerged as botha significant academic concept and a practical approach to enhancingworkplace culture andemployee retention. Through the lens of Social Exchange Theory (SET), WPS fosters reciprocal relationships in which meaningful work and shared values are exchanged for commitment and loyalty. As such, WPS not only directly enhances retention but also increases employee engagement (EE), which in turn reduces turnover intention(Beehner & Blackwell, 2016; Saks, 2011).

Person-Organizational Fit (POF)

Person-Organizational Fit refers to the perceived alignment between a company's values and the values of its employees and workplace characteristics(Kristof-Brown et al., 2023). Employees' values, goals, and characteristics are an expression of their identity and integrity(Siyalet al., 2020). Aligning POF can generate reciprocal advantages when employee needs and organizational demands intersect (Kristof-Brown et al., 2023), and it tends to be positively related to work contentment and job satisfaction(Risman et al., 2016). Therefore, building a positive perceived alignment enhances the organization's ability to impel, empower, and nurture high-performing talent. POF is measured by asking about individual and organizational values(Roczniewska et al., 2018). POF is supported by three main dimensions between employees and the organization: similarity of characteristics, consistency of objectives, and balance between values(Tugal & Kilic, 2015). According toKristof (1996), the indicator variables of POF include: a) value compatibility is the balance between employee and organizational intrinsic values; b) goal congruence is the consistency between employee and organizational goals, comprising leaders and coworkers; c) employee need fulfilment includes achieving equilibrium between the strengths inherent in the work environment with organizational systems and structures; and d) culture-personality congruence emphasizes the compatibility between an employee's personality traits and organization ideology. From a SET perspective, POF fosters mutual understanding between the employee and the organization. This reciprocity strengthens emotional ties, which translates into higher engagement and a decreased desire to leave. Several studies have confirmed that the relationship between POF and turnover intention is mediated by engagement(Biswas & Bhatnagar, 2013; Peng et al., 2014).

Employee Engagement

Employee engagement is crucial for driving organizational growth and achieving a competitive advantage. Engaged employees are more focusedon and dedicatedto business management(Khajuria & Khan,2022). Initially, the term ‘employee engagement’ became popular in the 1990s and was used by psychologist Kahn. Kahn defined engagement as the ability to bring your whole self, authentically, to work, and the three identified indicators include physical, cognitive, and emotional(Decuypere & Schaufeli, 2020). Ngozi and Edwinah (2022)defined the variable as the level of commitment individuals possess toward their work, encompassing cognitive, emotional, and behavioral aspects. According toSahni (2021), employee engagement leads to productive work outcomes and has a positive impact on the organizational environment. This included physical, psychological, and emotional enthusiasm. Shuck et al. (2017)described employee engagement as a positive mental statein which employees bring astrong cognitive investment, emotional connection, and motivated behaviors to their work. In the business world, this variable is a combination of job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and extra-role behavior(Schaufeli, 2013). Engaged employees, who are less distracted by personal issues due to their focus on tasks, tend to demonstrate increased productivity . In addition, prioritizing tasks can also lead to greater productivity and job satisfaction, resulting in decreased turnover (Le et al., 2023).This results in increased employee retention with decreased turnover intention.

Turnover Intention

Turnover intention refers to an employee's intention and willingness to voluntarily quit their job within a specified period. It is asignificant issue for organizations, affecting both performance and company continuity, as well asthe associated costs of recruiting staff(Fattah et al., 2022). A combination of psychological and organizational factors influences this intention, affecting employee perceived job satisfaction, pay and benefits, leadership style,and company support (Chatzoudes & Chatzoglou, 2022; Kanchana & Jayathilaka, 2023; Li et al., 2022) .Typically, this intent is due to voluntary choices, such as seeking a better job; however, it can also be guided by a perceived lack of a good fit with the organizational culture. Understanding these contributors is crucial to effective retention planning, particularly in the increasingly competitive higher education sector.

Hypotheses Development

The Effect of Workplace Spirituality and Turnover Intention

One significant area of academic inquiry is the effect of workplace spirituality on voluntary turnover. While research in Western contexts has identified negative associations between WPS and turnover intention(Cortese et al., 2014; Ghadi, 2017; Janik & Rothmann, 2015), this mechanism remains underexplored in Indonesia, where spirituality is often more deeply embedded in daily and professional life. Beehner and Blackwell (2016)found that enhanced WPS leads to lower turnover intentions, with similar findings from Ghayas and Bhutto (2020)in Turkey. Korkmaz and Menge (2018)emphasize that workplace spirituality significantly contributes to increased organizational commitment in educational settings, demonstrating that spiritual experiences in the workplace enhance teachers' sense of belonging and meaning in their work. This study also indicates that the dimension of workplace spirituality can serve as a binding force between individuals and educational organizations. However, scholarssuch as Kaymaz et al. (2014) emphasize the need for a deeper understanding of theemotional factors underlying this relationship. In Indonesia, the intertwining of spirituality with work ethics and social relationships is quite profound. In this context, employees tend to have a deeper moral and social connection to their organizations, making WPS especially pertinent. The prevailing corporate culture in Indonesia, which focuses on WPS, may have a stronger impact compared to individualistic Western cultures because Indonesia is more collectivistic, values social harmony, and is more religiously pluralistic. Therefore, the influence of WPS on employees' decisions to leave may be compounded by the culture's WPS relationships.

H1: WPS Negatively Affects Faculties' Turnover Intention

Person-Organization Fit and Turnover Intention

Person-Organization Fit (POF)refers to the alignment between an individual's and an organization's work values, goals, and practices. Many studies have documented its particular impact on job satisfaction and retention(Cennamo & Gardner, 2008; Verquer et al., 2003). Margaretha et al. (2023)reported a notable association between POF and turnover intention in a study with 366 employees. Research from other countries, such as Korea (Jung & Yoon, 2013) and Taiwan (Peng et al., 2014), also highlights that the POF enhances feelings of belonging and reduces turnover. POF’s effects, however, might differ from one culture to another. Within the collectivist framework of Indonesia, the culture places a strong emphasis on loyalty to the workplace and social harmony. There is greater employee loyalty to the group than to individual preferences. This suggests that POF is likely stronger in Indonesian universities, where alignment with institutional values, leadership, and collegial support is crucial. Therefore, perceived misalignment may result in a greater mismatch in anger and dissatisfaction compared to individualistic cultures.

H2: POF Negatively Affects Faculty Turnover Intention

The Mediating Role of Employee Engagement

Employee Engagement (EE) is defined as the level to which an employee is cognitively, emotionally, and behaviorally involved in their work (Schaufeli, 2013). The retention and productivity of the organization deeply rely on engaged employees who display enthusiasm, focus, and stamina. WPS aids in EE through meaningful and purposeful work experiences, whereas POF enhances EE through congruence of values and psychological safety (Biswas & Bhatnagar, 2013; Garg, 2017). Hence, engagement serves as a key mediator, transforming intangible motivational factors into behavioral outcomes, in this case, reduced turnover intention. In Indonesian workplaces, where emotional bonds, loyalty, and spiritual meaning hold immense value, EEserves as a strong mediator of intangible motivations for retention. This aligns with Social Exchange Theory and Conservation of Resources Theory, which suggest that individuals are more likely to remain committed when organizations reciprocate their psychological and emotional investment(Hobfoll, 1989; Saks, 2011). Thus, within the framework of Indonesian culture, engagement serves the purpose of connecting internal motivational elements with the intention to leave the job; however, in this case, it may also be heightened by social expectations and group standards.

H3: Employee Engagement Mediates the Effect of WPS on Faculty Turnover Intention

H4: Employee Engagement Mediates the Effects of POF on Faculty Turnover Intention

Figure 1. Research Model

Methodology

Research Sample

The study collected data from 1026 faculty members employed at Indonesian public and private universities. It was mandatory for faculty to have at least one year of teaching experience. Participants were from various regions, including Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Eastern Indonesia, to ensure diverse institutional coverage. The sampling method used was purposive, focused on gaining relevant scholarly teaching faculty within and across geographic and organizational boundaries. Data collection was conducted through self-administered questionnaires. The questionnaires were administered in two ways: through in-person visits to the institutions and electronic channels via communication applications.Although the sampling was not entirely random, efforts were made to ensure proportional representation from various types and areas of institutions, thereby strengthening the reliability of the study.

Research Instruments

Each variable was measured using instruments developed in previous research. The Workplace Spirituality (WPS) questionnaire consisted of 21 items adapted from Ashmos and Duchon (2000). One example statement is: "The spirit I have energizes the work I do". Person-Organization Fit (POF) was measured using a three-item scale adapted from(Tugal & Kilic, 2015), with a sample item such as: "My values match those of the organization I work for". The Turnover Intention (TOI) scale, adapted from Kim (2018), consisted of five items. One example statement is as follows: "If I had the opportunity, I would leave my job at any time". Lastly, the Employee Engagement (EE) questionnaire was developed based on the questionnaire prepared by Decuypere and Schaufeli (2020), which included 17 items. One example item is: "At work, I always feel full of energy". All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree.

To mitigate the risk of common method bias (CMB) associated with the self-reported nature of the data, several procedural remedies were implemented during the data collection phase. First, the procedures were designed to protect anonymity and confidentiality, thereby limiting social desirability bias and evaluation apprehension. Second, the survey was pretested to prevent ambiguity and overlap between items. Third, predictor and criterion variables were grouped in such a way that they were in different sections of the survey to prevent consistency motifs. Moreover, following the guidelines of Podsakoff et al. (2003), Harman’s single-factor diagnostic test was performed, and the results showed that no single factor accounted for most of the variance, suggesting that common method bias was not a serious issue. Further, collinearity checks using VIF values confirmed that all values were below the conservative cut-off of 3.3, which supports the absence of multicollinearity that could suggest common method bias in PLS-SEM models(Hair et al.,2021).

Respondent Characteristics

To efficiently gather data, researchers employed a dual distribution strategy for the questionnaires, using both direct and mail surveys. In this context, respondents were asked to fill out the questionnaire online. The survey was conducted over three months, with 1,026 faculty members from public and private universities participating in completing the questionnaire. Table 1presents the respondent profile, with 60.5% of the respondents being female and an average age of 36.3 years, ranging from 30 to 39 years old .Additionally, 65.2% held master's degrees, and 22.8% had 1-5 years of work experience. A total of 73.8% of the attendees were from private universities in Indonesia, and 73.8% of the faculty were married.

Table 1. Respondents Characteristics

| Dimensions | Category | Total | Percentage |

| Gender | MaleFemale | 405621 | 39.5%60.5% |

| Type of University | State UniversitiesPrivate Universities | 330696 | 26.2%73.8% |

| Age | <30 years oldAges 30-39 Ages 40-49 Ages 50-59 >=60 years old | 14237230417236 | 14.0%36.3%29.5%16.7%3.5% |

| Marital Status | UnmarriedMarried | 191835 | 18.6%81.4% |

| Last Education | S1S2S3 | 66669291 | 6.4%65.2%28.4% |

| Years of experience | <5 years tenure5-10 years tenure10-15 years tenure16-20 years tenure20-25 years tenure>25 years tenure | 23425316312218272 | 22.8%24.7%15.9%11.9%17.7%7.0% |

| Faculty | Economics and BusinessSocial Science & Political ScienceEngineeringLanguage and CultureInformation Technology Math and ScienceArt and DesignTeachingAgriculturePsychology Others | 67781873231681361075 | 66.0%7.9%8.5%3.1%3.0%.60%0.8%1.3%.60%1.0%7.3% |

Data Analysis and Hypothesis Testing

Data analysis was conducted to evaluate the validity and reliability of the instruments. Subsequently, Smart PLS 4 was used to run the model and test the hypothesis. To ensure the instrument's validity and reliability, a rigorous outer model evaluation was conducted. There were two evaluations of validity: convergent and discriminant. Convergent validity was evaluated using the loading factor and average variance extracted (AVE) values. Discriminant validity was obtained from the Fornell-Larcker criterion and cross-loading.To examine the strength of the relationships among the measurement and latent variables in the path analysis, a critical evaluation of the loading factors was undertaken, as presented in Table 2.Themanifest variables withan outer loading of .70 or higherwere pleasing beyond expectations. Henseler et al. (2009)mentioned that variables with loading values between 0.40 and .70 should be re-examined before being eliminated. In this research, items with values less than or greater than .60 were eliminated or evaluated. Testing revealed that several questions did not meet the required criteria and had to be eliminated for further stages. For employee engagement (EE), there were 11 valid questions, comprising three, four, and six for POF, turnover intention (TOI), and WPS, respectively.

Table 2. Loading Factors

| Items | Loading factors | Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite reliability (rho_a) | Composite reliability (rho_c) | AVE |

| EE1 | .701 | .912 | .917 | .926 | .534 |

| EE10 | .727 | ||||

| EE11 | .805 | ||||

| EE13 | .656 | ||||

| EE2 | .779 | ||||

| EE3 | .665 | ||||

| EE4 | .745 | ||||

| EE5 | .817 | ||||

| EE7 | .768 | ||||

| EE8 | .636 | ||||

| EE9 | .710 | ||||

| POF1 | .876 | .895 | .905 | .935 | .827 |

| POF2 | .944 | ||||

| POF3 | .906 | ||||

| TOI1 | .777 | .876 | .900 | .915 | .729 |

| TOI3 | .862 | ||||

| TOI4 | .892 | ||||

| TOI5 | .879 | ||||

| WPS10 | .736 | .825 | .829 | .873 | .533 |

| WPS16 | .713 | ||||

| WPS17 | .767 | ||||

| WPS18 | .682 | ||||

| WPS3 | .729 | ||||

| WPS7 | .752 |

Another parameter used to evaluate the consistency of the measurement instrument is theAVE. The value examines whether a latent variable accounts for a significant portion (over 50%) of the variance on average. Therefore, a latent variable has good convergent validity when theAVEvalue is greater than .50. Table 2 shows that all four variables meet the criteria (AVEvalue > .50).Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability (CR) values were evaluated to determine the effects ofthe manifest variableson measuring latent constructs.Compared to Cronbach's alpha, composite reliability is considered amore robust measure of internal consistency due to itsuse of standardized loadings of manifest variables.The testing results in Table 2 showed that the variables have satisfactory Cronbach's alpha values (EE = .912; POF = .895; TOI = .876; WPS = .825), andCRvalueswere greater than .70. The subsequent stage tested discriminant validity based on cross-loading. The indicator successfully distinguished the construct it was designed to measure from other constructs when the cross-loading value was the largest compared with the other variables.

Table 3. Cross Loading Analysis

| Items | EE | POF | TOI | WPS |

| EE1 | .701 | .451 | -.158 | .457 |

| EE10 | .727 | .272 | -.236 | .600 |

| EE11 | .805 | .312 | -.227 | .611 |

| EE13 | .656 | .321 | -.140 | .439 |

| EE2 | .779 | .372 | -.210 | .627 |

| EE3 | .665 | .259 | -.201 | .511 |

| EE4 | .745 | .421 | -.166 | .489 |

| EE5 | .817 | .353 | -.252 | .574 |

| EE7 | .768 | .348 | -.199 | .546 |

| EE8 | .636 | .298 | -.064 | .363 |

| EE9 | .710 | .306 | -.120 | .524 |

| POF1 | .401 | .876 | -.104 | .228 |

| POF2 | .451 | .944 | -.200 | .279 |

| POF3 | .404 | .906 | -.162 | .233 |

| TOI1 | -.140 | -.128 | .777 | -.167 |

| TOI3 | -.210 | -.137 | .862 | -.190 |

| TOI4 | -.220 | -.181 | .892 | -.193 |

| TOI5 | -.268 | -.146 | .879 | -.263 |

| WPS10 | .557 | .227 | -.137 | .736 |

| WPS16 | .497 | .135 | -.153 | .713 |

| WPS17 | .555 | .212 | -.199 | .767 |

| WPS18 | .435 | .120 | -.199 | .682 |

| WPS3 | .511 | .197 | -.207 | .729 |

| WPS7 | .597 | .279 | -.176 | .752 |

The second parameter for assessing discriminant validity is the Fornell-Larcker value. The purpose of the analysis was to ensure that the measured constructs weredistinct and notoverlapping(Hair et al.,2021). Therefore, the correlation value should be smaller thanthat of the construct, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Fornell-Larcker Criterion

| Variables | EmployeeEngagement | POF | TurnoverIntention | WorkplaceSpirituality |

| EE | .730 | |||

| POF | .461 | .909 | ||

| TOI | -.253 | -.174 | .854 | |

| WPS | .724 | .272 | -.243 | .730 |

Findings

The means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for the main study variables, which include WPS, EE, TOI, and POF, are shown in Table 1. The average score for WPS was 4.38 (SD= .30), indicating that respondents generally reported a high level of positive workplace spirituality. Employee engagement also demonstrated a similarly high mean of 4.28 (SD= .33), suggesting strong engagement among participants. In contrast, turnover intention exhibited a lower mean of 2.38 (SD= .70), reflecting that, on average, respondents reported relatively low intentions to leave their organization. Person-organization fit showed a moderate mean score of 3.53 (SD= .72).

Table5. Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations for Study Variables

| Variable | M | SD | WPS | EE | TOI | POF |

| WPS | 4.38 | .30 | 1 | |||

| EE | 4.28 | .33 | .62** | 1 | ||

| TOI | .70 | .70 | -.29** | -.25* | 1 | |

| POF | .72 | .72 | .36** | .32** | -.16* | 1 |

Note: *p.05, **p<.01

Consistent with theoretical expectations, WPS and EE were positively and strongly correlated (r= .62,p< .01), indicating that better workplace spirituality conditions are associated with higher employee engagement. Both WPS and EE were negatively correlated with turnover intention (r= -.29,p< .01;r= -.25,p< .05, respectively), suggesting that positive work conditions and engagement are linked to lower employee intentions to leave. Person-organization fit was moderately and positively related to both WPS (r= .36,p< .01) and EE (r= .32,p< .01), and negatively related to turnover intention (r= -.16,p< .05), indicating that greater fit between person and organization tends to align with more favorable workplace conditions and attitudes, as well as reduced intentions to quit. Overall, the descriptive statistics reveal generally favorable perceptions of the majority of work-related variables, while the pattern of correlations supports the hypothesized directions among study constructs.

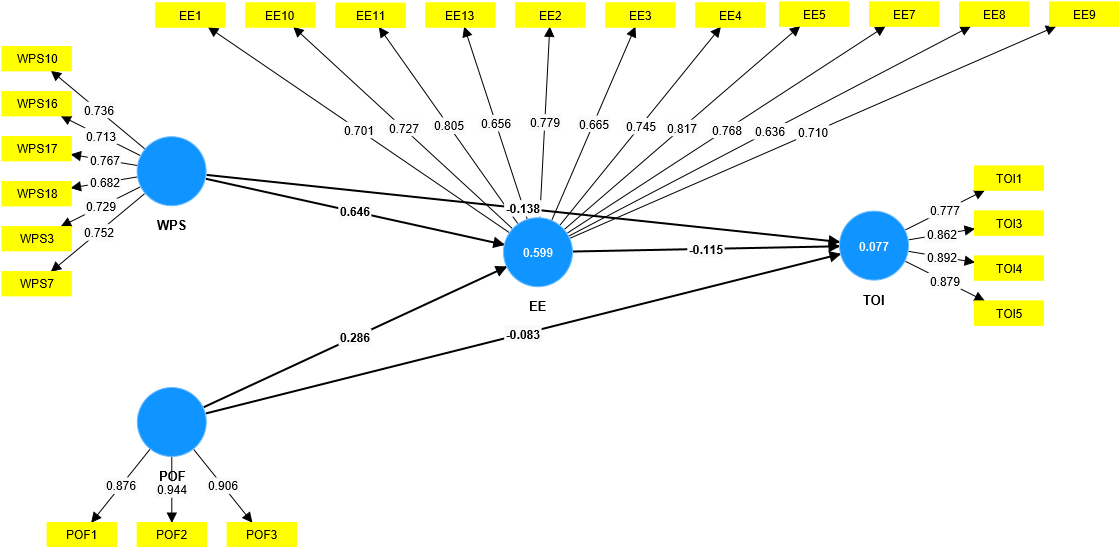

The structural model was evaluated using several indicators, including the R-squared value, path coefficient,t-statistic value, predictive value, and model fitness. The model has an R-squared value of .599 and .077 for engagement and turnover intention, respectively. This explains why WPS and POF affect engagement by 59.9%. Meanwhile, WPS, POF, and EE as mediating variables affected turnover intention by 7.7%. TheR²value for Turnover Intention (TOI) was relatively low (.077), suggesting that only 7.7% of the variance in TOI can be explained by WPS, POF, and EE combined. This suggests that other variables not included in the model may have a significant impact on turnover intention. Conversely, the R²for Employee Engagement (EE) was .599, showing that WPS and POF accounted for nearly 60% of its variance, reflecting a more substantial predictive capacity. This discrepancy highlights the need for future studies to consider additional psychological or contextual variables that may better explain TOI in academic settings.

Table6. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

| Variables | R-squared | R-squared adjusted |

| EE | .599 | .598 |

| TOI | .077 | .074 |

The subsequent stage assessed the path coefficients of the latent variables by comparing the β values. The relationship between paths can beconsidered significant when the t-statistic value is greater than 1.96 and thep-value is smaller than .05. The test results indicate that employee engagement and POF have a significant direct effect on intention to transfer (p= .031andt-statistic > 1.96). The indirect relationship between the variables was also reported to be significant. The direct relationship among WPS, turnover intention,and engagement was significant; hence, the hypotheses were accepted.

Table7. Path Coefficient

| Path | Original sample (O) | Samplemean (M) | Standard Deviation(STDEV) | T statistics(|O/STDEV|) | p values | Decision |

| EE TOI | -.115 | -.114 | .053 | 2.163 | .031 | Accepted |

| POF EE | .286 | .286 | .030 | 9.512 | .000 | Accepted |

| POF TOI | -.083 | -.083 | .041 | 2.026 | .043 | Accepted |

| WPS EE | .646 | .646 | .025 | 26.210 | .000 | Accepted |

| WPS TOI | -.138 | -.141 | .048 | 2.887 | .004 | Accepted |

| POF EE TOI | -.033 | -.033 | .016 | 2.009 | .045 | Accepted |

| WPS EE TOI | -.074 | -.073 | .034 | 2.183 | .029 | Accepted |

The predictive or Q-squared valuewas tested in SmartPLS using the blindfolding procedure(Henseler et al., 2009). The results show that engagement and turnover intention haveQ-square values greater than zero,indicating a significant relationshipwith good observation values.

Table8. Predictive Value Analysis

| Variables | Q²predict | RMSE |

| EE | .595 | .639 |

| TOI | .066 | .970 |

A goodness-of-fit (GoF) test was conducted to assess the model's ability to explain the relationship between the latent variables and indicators. The variables were evaluated based on the Normed Fit Index (NFI). The result obtained for the Normed Fit Index (NFI) in this study was .882, which is slightly acceptable. For PLS-SEM, especially in exploratory studies, NFI values above .80 are deemed acceptable (Hair et al.,2021). UnderNFI’s conventional threshold of .90 in covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) PLS-SEM is more forgiving, especially for intricate models or larger samples. Additional model fit assessment was calculated, and the following fit indices were obtained: SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residual)= 0.055, which is below 0.08. The fit indicesd_ULSandd_Galso met the appropriate thresholds in relation to their bootstrapped cut-off values. In addition, the R² values, Q² values, and the predictive relevance (PLS predictive) demonstrated the structural model’s explanatory and predictive validity. Hence, the slight drop in NFI, at .90, is counterbalanced by the strong model fit presented by other measures,such as SRMR,R²,Q², and NFI together. The results of the structural model testing are presented in Figure 2.

Table9. Goodness of Fit Model

| Saturated Model | Estimated Model | |

| SRMR | .055 | .055 |

| d_ULS | .900 | .900 |

| d_G | .257 | .257 |

| Chi-square | 1554.412 | 1554.412 |

| NFI | .882 | .882 |

Figure 2. Structural Model Test Results

Discussion

WPS fosters a supportive environment that promotes spiritual and emotional growth towards greater purposes. This variable needs to be cultivated to support spiritual well-being, sense of purpose, satisfaction, and transcendence(Vasconcelos, 2018,2023). Earlier studies have also shown that this study reinforces the significant influence of workplace spirituality in encouraging faculty engagement and reducing turnover intention. According to Cortese et al. (2014), Ghadi (2017), Ghayas and Bhutto (2020), Janik and Rothmann (2015), the mediating variable significantly and negatively affects turnover intention and engagement. WPS fosters intrinsic motivation, helping employees become more engaged in their work tasks . Jnaneswar and Sulphey (2023) pointed out that predicted mindfulness and self-compassion ultimately lead to well-being. In the context of this research, universitiesthat prioritize WPS activelyfoster a culture of strong employee engagement. For the purposes of this research, universities that place an emphasis on WPS are those that actively support a climate of high employee engagement. This focus on WPS creates a sense of meaningfulness at work, which significantly mitigates employees' intention to leave. As previous studies found(Jnaneswar & Sulphey,2023; Vasconcelos,2023), WPS offers intrinsic motivation through enhancing employees' sense of purpose, ethical awareness, and psychological well-being. Within the context of the current study, universities that foster spiritual values and a shared meaning in work develop work environments where faculty experience esteem and motivation. This finding validates Social Exchange Theory, revealing reciprocal relations between organizations and individuals. These findings confirm those of Korkmaz and Menge (2018), who found that workplace spirituality increases commitment to organizations among educators, thereby enhancing the meaning, association, and purpose of work. Their work still suggests that in academic settings, where identity and calling sometimes coexist, spiritual experiences tend to foster emotional attachment to the institution and thus reduce turnover intentions.

Similarly, POF was found to be a significant predictor of employees’ intention to stay. POF refers to the degree of similarity between individuals andorganizationsdue to character compatibilitybetween both entities(Subramanian et al.,2023).Drawing on COR Theory, findings suggest alignment between personal and organizational values minimizes emotional strain and bolsters psychological well-being. This alignment strengthens commitment, particularly in value-driven professions such as academia.POF emotionally binds employees to their assigned tasks after they have experienced transcendence through work. Therefore, the level of engagement increases, while the tendency to change jobs decreases,when faculty members are fit with the university. This supports the findings of Rattanapon et al. (2023), who include cross-generational employees, where POF reduces the tendency to change jobs. These results are expected to be consistent with earlier studies(Dalgic, 2022; Margaretha et al., 2023; Peng et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2017). Theoretically, this study contributes to the development of Social Exchange Theory (SET) and Conservation of Resources Theory (COR) by demonstrating how intangible psychological resources, such as meaningful work and value alignment, translate into reduced withdrawal intentions through engagement. These findings expand the understanding of SET and COR in educational contexts, particularly where relational and cultural capital are key to employee retention.

The relatively lowR²value of .077 for turnover intention suggests that WPS, POF, and EE explain only a small fraction of the variation in faculty members’ intention to leave. This implies that most of the influencing factors, around 92% are likely related to other elements not examined in the present model. In behavioral and human resource research, such findings are common, as employees’ decisions to resign are often shaped by a broad range of organizational and external conditions, including but not limited to remuneration satisfaction, perceived workload, career advancement prospects, leadership approach, workplace culture, and labor market dynamics(Chatzoudes & Chatzoglou, 2022; Kanchana & Jayathilaka, 2023). Thus, the model demonstrates considerably greater predictive strength for employee engagement (R² = .599) than for turnover intention. From a managerial perspective, the results indicate that while WPS and POF play a role in lowering turnover intentions, their influence is limited and should be supported by additional measures at both strategic and operational levels. University administrators may therefore consider a more comprehensive retention strategy, one that balances value alignment and meaningful work with competitive compensation, career development programs, flexible working arrangements, and a positive institutional climate. Future research could enhance the explanatory scope of the model by incorporating additional variables, such as job satisfaction, perceived organizational support, work–life integration, or broader employment market trends.

Furthermore, the mediation analysis revealed significant indirect effects of both WPS and POF on turnover intention through employee engagement. The indirect effect of WPS on turnover intention via engagement was β= -.134 (CI 95%: -.208 to -.064), while POF had an indirect effect of β = -.115 (CI 95%: -.188 to -.049). These confidence intervals exclude zero, confirming the significance of the mediation paths. This suggests that engagement serves as a reliable psychological mechanism through which spiritual alignment and value congruence reduce the faculty's desire to leave.

While the mediating effect of employee engagement was statistically supported, further insights could be gained by comparing the magnitude of engagement across different industries or cultural contexts. Cultural factors, such as collectivism and high power distance, common in Indonesian workplaces, likely amplify the impact of WPS and POF. In collectivist societies, shared values and communal meaning play a crucial role in fostering loyalty and a sense of belonging. Moreover, when senior figures actively model spiritual values, employees may feel a stronger obligation to reciprocate through commitment. These cultural dimensions may explain why relational constructs, such as WPS and POF, have a significant influence on turnover intention in Indonesian universities. Compared to prior studies conducted in Western contexts(Biswas & Bhatnagar, 2013; Milliman et al., 2018), this research found a stronger mediating role of engagement, possibly due to the more collectivist and relational nature of academic communities in Indonesia. Unlike the findings of Ghadi (2017), who reported weak mediating effects, the current study highlights engagement as a robust conduit, particularly when WPS is institutionalized. For higher education management, the findings offer actionable strategies. Integrating WPS into institutional culture, through reflection sessions, ethical leadership development, and shared purpose narratives, can foster faculty resilience and connection. Additionally, aligning recruitment and appraisal systems with institutional values enhances POF. These steps are vital in addressing turnover challenges and meeting accreditation demands in Indonesia’s dynamic tertiary sector.

Conclusion

This research provides evidence of the critical impact of Workplace Spirituality (WPS) and Person–Organization Fit (POF) on reducing turnover intention among faculty members, with Employee Engagement serving as a significant mediating factor. The results reveal that POF, as well as WPS, is negatively correlated with faculty members’ intention to leave the organization, thus underlining the relevance of intrinsic motivation in sustaining enduring organizational commitment. This study further expands the understanding of non-financial retention factors by incorporating concepts of spiritual and congruence values within the context of organizational behavior theory. This is the first and foremost application of WPS and POF in the context of non-profit education, turning to a business-like model of operation. The integration of Social Exchange Theory and Conservation of Resources Theory provides a coherent framework for explaining how psychological attachment and personal and organizational alignment influence turnover intention. In terms of methodological contribution, the use of a large, diverse sample of 1,026 faculties across both public and private institutions enhances the robustness and generalizability of the findings within the Indonesian higher education sector, an area that has previously lacked large-scale empirical exploration. From a practical standpoint, the results offer actionable insights for university leaders and policymakers. Institutions are encouraged to foster a work environmentthat supports spiritual growth, aligns institutional values with those of academic staff, and strengthens personal meaning at work. Strategies may include mentoring programs, onboarding processes that emphasize the institutional mission, and initiatives focused on well-being and ethical leadership. These interventions are essential for cultivating engagement and reducing attrition. As noted, this study emphasizes the importance of considering motivational dynamics as intangible factors within the framework of human resource management policies, particularly in the academic context. As global competition intensifies and higher education institutions strive for excellence, retaining skilled faculty members through values-driven, purposeful engagement is vital not just for human resources but for institutional strategy.

Recommendations

This research provides practical and theoretical insights for higher education institutions and future researchers. First, universities should actively support WPS by creating a work environment that stresses meaningful work, ethical values, emotional well-being, and individual capacity for growth. These practices would be conducive to increasing organizational identification and reducing faculty's intention to leave. Second, university leaders must enhance person-organization fit (POF)by aligning organizational values withfaculty values. This can be achieved through targeted recruitment, impactful induction programs, and organizational interventions that promote the alignment of values and cultural fit. Third, work should be done to create more engaged employees. Commitment can be promoted through the use of participatory decision-making systems, mentoring, recognition and rewards, incentives, and involvement in the workflow.

Fourth, retention policies should extend beyond financial incentives by incorporating non-material rewards and psychological support mechanisms. Value-based strategies that emphasize personal meaning and organizational alignment are likely to yield more sustainable commitment and retention outcomes.

Limitations

Regarding the limitations, firstly, the data were collected through an online questionnaire administration, which relied on respondents' self-reporting. The method was biased because respondents limited their responses to certain questions, thus affecting the validity of the results. In this context, clear instructions were provided to respondents after they were selected for questionnaire completion. Second, since cross-sectional designs have limitations, future research should adopt longitudinal methods, such as experimental or time-series designs. Third, quantitative methods were employed to investigate the effects of WPS and POF on turnover intention, with engagement serving as a mediator. By conducting structured interviews with workers who willingly choose to quit the company, a further qualitative study could clarify this issue. Future research should investigate additional external factors that influence turnover intention beyond the scope of this study .Additionally, future studies should consider including moderating or mediating variables such as leadership style, perceived organizational support, or work-life balance to enrich the model and provide a more comprehensive understanding of turnover dynamics in academic settings.

This research was supported by the Institute for Research and Community Service at Maranatha Christian University.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that neither real nor perceived conflicts of interest exist.

Generative AI Statement

The authors have not used generative AI or AI-supported technologies.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Margaretha:Conceptand design, data analysis, writing, critical revision of manuscript, supervision, securing funding, and final approval.Sinuraya:Dataacquisition, technical support.Sherlywati:Technicalsupport, statistical analysis, resources. Zaniarti:Dataacquisition, admin.Saragih:Statistical analysis, data analysis, editing, resources. Margaretha:Dataacquisition, admin.