Introduction

It is beyond doubt that education enables us to develop, progress, and advance intoday's industrializedsociety. As education becomes increasingly vital for survival in the volatile and cutthroat world, it is important to ensure that humans from all walks of life, particularly children, acquire and solidify their knowledge (World Bank, 2019). However, learning levels among children in developing countries, including Malaysia, are critical due to a greaternumberof them being unable tomeet the expectations of national curricula, nor at the basic levels tested in “citizen-led” assessments, such as ASER andUWEZO (Crouch et al., 2021). Significantly,UNESCO has also estimated thatabout 617 million children across the globe did not even reach the basic levels in 2017, whiletheWorld Bank (2019) estimated that at the age of 10, half of the children in low and lower-middle-income countries are unable to read a simple paragraph. The learning crisis among children has become even more criticaldue tothe COVID-19 pandemic.This is due to the fact that learning poverty has increased to 70 percent from 57 percent in low- andmiddle-income countries as of 2022 (The State of Global Learning Poverty, 2022).

According to King et al. (2023), learning poverty is described as the inability of children to read and understand a simple text by the end of primary school. Corresponding to the authors' description of learning poverty, it has also been defined as a critical social problem (World Bank, 2019). Evidence from past research alsosuggests that learning poverty has led to learning loss among children, hindering their ability to acquire and retainknowledge (Pek et al., 2024). The authors describehow learning loss can cause children to experience a decline in knowledge and abilities, which in turnhinders their academic achievement and long-term educational outcomes. In Malaysia, the problem of learning loss is particularly concerning due to the young learnershavingfaced multiple challenges that contribute to this issue, including limited access to quality education, socioeconomic factors, and the uneven implementation of digital learning tools during the pandemic (Crouch et al., 2021; Pek et al., 2024).

The abrupt shift to online learning duringthe COVID-19 pandemic exposedchildren to the digital divide, where students from underprivileged backgrounds struggled to keep up due to limited access to technology and the internet (World Bank, 2019). Significantly, this situation has not only widened the gap between different socio-economic groups but also deepened learning poverty among the most vulnerable populations (The State of Global Learning Poverty, 2022). Additionally, the lack of preparedness and training among educators to effectively deliver teaching and learning through online platforms further worsens the problems (Pek et al., 2024). As evidenced by King et al. (2023), many teachers were not equipped with the necessary skills to engage students in a virtual environment, resulting in poor instructional quality and increasedlearner disengagementduring teaching and learning. The disengagement has been particularly detrimental to young learners, who require more interactive and hands-on learning experiences to understand foundational concepts (UNESCOInstitute for Statistics,2017).

Adding to the teachers’ unpreparedness, disruption in early childhood education is another significant issue contributing to learning losses in Malaysia, as this phase is crucial in influencing the later academic success of learners. The closure of preschools and early learningcentresduring the pandemic has caused learners to miss out on critical early learning opportunities, leading to gaps in language development, numeracy, and social skills. According to King et al. (2023), these early deficits in acquiring the foundation of learning have long-term implications, as learners who start school later than their peers are often unable to catch up, further perpetuating the cycle of learning poverty.

Addressing learning loss is critical to enabling learners to reach their full potential and achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4, which aims to promote inclusive and equitable quality education for all. Although learning poverty is increasingly identified as a global education issue, previous research has frequently lacked a comprehensive and systematic examination of its underlying causes, interconnected variables, and long-term consequences. In particular, there is a scarcity of bibliometric data evidence charting the intellectual environment and research patterns concerning educational learning poverty. To overcome this gap, this study takes a bibliometric approach, assessing the global research output on learning poverty over the last decade (2014-2023) using data from the Scopus database.

The study usesvisualisation, co-author networks, keyword grouping, and thematic mapping to identify major contributions, emerging themes, research hotspots, and potential gaps in the literature. This extensive analysis is likely toenhance our understanding of the scientific academic debate on learning poverty and provide insights that will enablefocused efforts to reduce global learning loss.

Methodology

This researchutiliseda bibliometric analysis,which was further described through quantitative and statistical analysis, aiming to illustrate distribution patterns of past studies for specific topics and time periods (Martí-Parreño et al., 2016). Similarly, this research is used to describe a collection of relevant literature based on bibliographic data. According to Ahmi and Mohamad (2018), this method of analysis is highly used due to itsability to enableresearchersto present the trends and patternsof studies. This research on learning poverty illustrates the patterns of the literature through the classification of authors and countries. Additionally, the number of citations, citations per year, and h-index were measured to show the impact and performance of the retrieved literature. Significantly, this research also providesvisualization and mapping for co-authorships, co-citation, and co-occurrence of keywords or terms to identifyprevious, current,and future trends regarding learning poverty.

To conduct this analysis, the Scopus dataset was retrieved as the primary source for the data collection on learning poverty. Scopus database has been chosen as the primary source for bibliometric analysis due to Scopus being the most effective and largest searchable abstract and citationdatabase, in comparison with the available databases,includingWoSand Google Scholar. As Scopusis the largest searchable database, it includes more than 7000 publishers and indexesmore than 23.4 million open-access items. This makes it an ideal tool for a thorough bibliometric study. The database was accessed on August 1, 2024, and literature was retrieved using a strategic combination of keywords: “learning poverty”, “learning loss”, and “reading loss”.

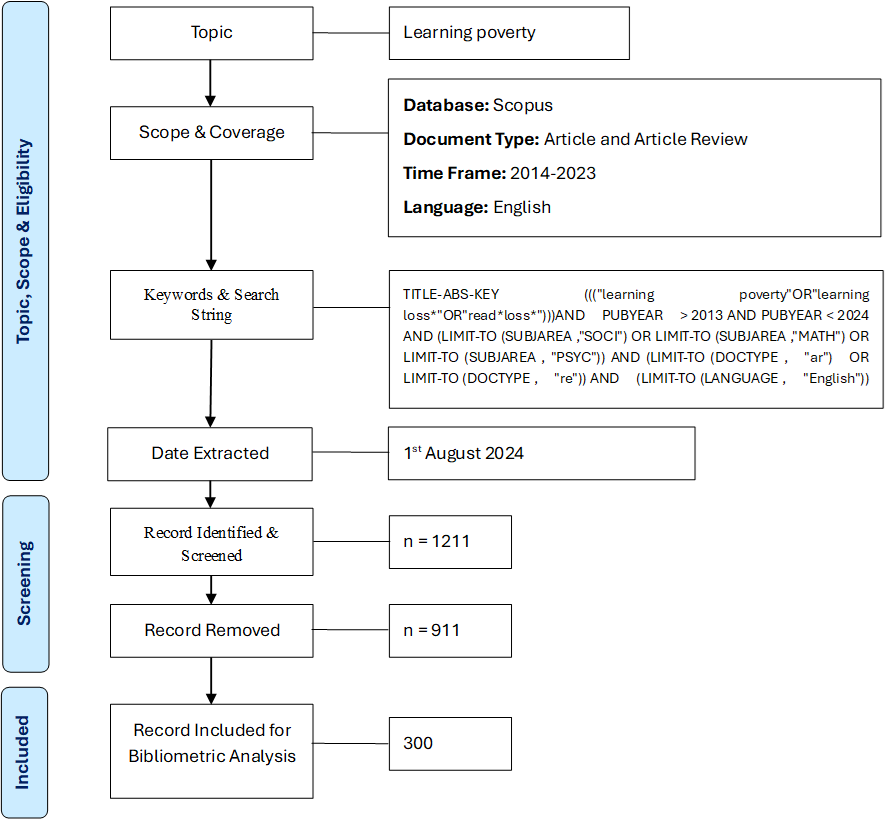

The retrieved documents for this research were constructed based on the research protocol guided in Figure 1. Following the PRISMA framework, the search parameters were carefully defined to ensure the relevance and accuracy of the dataset, yielding an initial result of 1,211 retrieved. The search spanned a decade, from 2014 to 2023, with a focus on specific subject areas relevant to education, thesocial sciences, and literature. A decade-long period was established to encompass both fundamental and emerging themes inresearch on learning poverty. This analysis specifically addresses the pre- and post-COVID-19 periods, which markedly affected educational disparities (Crouch et al., 2021). This timeframe providessufficient data for a comprehensive bibliometric analysis, capturing the dynamic worldwide conversation regarding learning poverty simultaneously.

Additionally, only articles and review articles published in English were included to maintain consistency in the dataset, recorded in 302 journals retrieved for bibliometric analysis. The filtering process is important as it reflects and influences the research in the field of learning poverty. After exporting the dataset from Scopus database, the data were processed andanalysedusing several tools, including Microsoft Excel to generate descriptive statistics and visual representations of trend through relevant charts and graphs,Harzing’sPublish and Perish software was then used to produce the citation metrics such as the total number of citations, citations per year, the h-index, which collectively provide insights into the impact and scholarly influence of the retrieved literature.

Apart from that,VOSviewer, a software tool specifically designed for constructing andvisualisingbibliometric networks, wasutilisedto create co-occurrence maps. The co-authorship analysis highlights the collaboration patterns amongresearchers, while the co-citation analysis aids the authors in identifying influential and significant papers that revolve around the topic of learning poverty. Lastly, the co-occurrence analysissearches for the main topics and emerging trends in the literature that focuson learning poverty. Essentially, the methodologies employed for the study not only focus on the growth and development of research on learning poverty but also provide insights into its global distribution and collaborative networks that are primarily working in this field. The results aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of how learning poverty has been studied over the past decade and identify future research directions to address this critical issue.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram of Systematic Searching Techniques

Source: Primary Data

Results

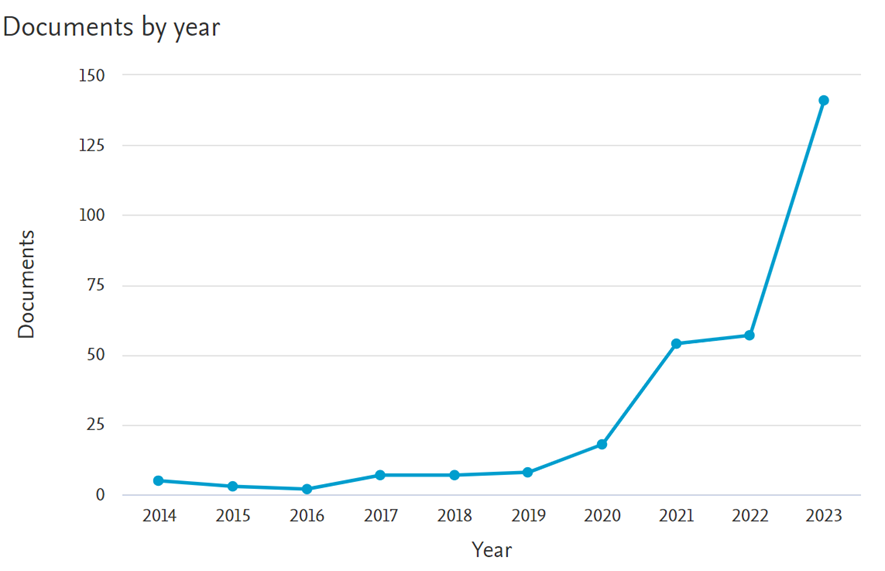

The graph shown in Figure 2 illustrates a clear upward trend in publications, whichis particularly evident in the later years, as indicated bythe annual number of published documents related to learning poverty from 2014 to 2023. As can be seen in Figure 2, 2014 to 2020 is described as a period of stability and slow growth due to the number of published documents remaining relatively low and stable. During these years, the publication count fluctuated slightly but generallyremained below 25 documents per year. The most published journalwas in 2020, with 18 documents. Thissuggests that the topic of learning poverty may not have been a primary focus within academic research during this period; however,it was in its early stages of scholarly attention due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the other hand, the initial increasebegan in 2020 and continued into 2021,as there was a noticeable but still modest increase in the number of published documents. This increase could be attributed to the growing awareness of learning poverty issues,particularly as the COVID-19 pandemic has caused global challengesin all fields, including education. As the pandemic swept across the globe, it brought significant changes to the way knowledge is delivered, exposing educational inequalities and contributing to widespread learning loss. Consequently, the increase in publication counts in 2021 reflects a growing interest in this area, as the pandemic’s impact on education became more evident.

Notably, the graph shows the most significantrise in publications that occurred between 2022 and 2023. In 2022, the number of documents published nearly doubled compared to 2021, and by 2023, the publication count had skyrocketed to 141 documents. This notable increase likely reflects the intensified focus on learning poverty as a critical global issue, with more researchers addressing the educational challenges heightened by the prolonged effects of the pandemic. The solid growth in publications during these years also indicates that learning poverty has become a significant topic of interest in the academic community, leading to an expanded body of research.

Generally, the trend described through the graphs shows a significant increase in the number of published documents on learning poverty from 2020 to 2023. Therefore, this trend illustrates how learning poverty gained interest in educational challenges research areas due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, it also highlights the growing recognition of theimportance of addressing learning poverty at this current time and its implications to educational policy and practice worldwide.

Figure 2. Publications Trend by Year

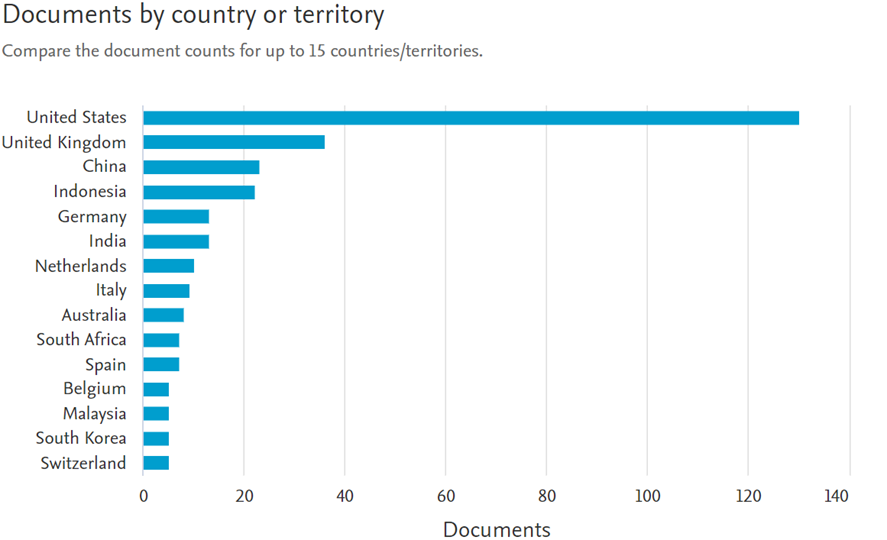

As shown in Figure 3, the graph illustratesthe contributions of various countriesto the scholarly literature on learning poverty. The leading contributor to learning poverty, with 130 publications, was from the United States,which highlights the country'srobust academic infrastructure and a strong focus on educational inequality and social justice issues. The significantly influential responses from the U.S. academic community have resulted in a substantial share of global research on learning poverty. Following the United States, the United Kingdom and China are also the major contributors to the field, with 36 and 26 publications, respectively. The UK, with its long-standing tradition of research in education and social policy, has generated significant work, while China's expanding academic influence has a notable influence in addressing the educational disparities within its vast and diverse population.

The widespread global involvement regarding learning poverty includes Indonesia, Germany, India, the Netherlands, Italy, Australia, and South Africa. Spain, Belgium, Malaysia, South Korea, and Switzerland have the most published documents, with 22, and the 15thplace with five publications. The contributions of these countriesemphasisethe global concern over learning poverty, with research emerging from different regions, each offering perspectives shaped by their unique socio-economic and cultural contexts.

Figure 3. Published Documents by Countries

Table 1presents the dataset retrieved from the Scopus database from 2014 to 2023, comprising a total of 300 articles on learning poverty, with an accumulated h-index of 31. The g-index is reported as 59, and the total number of citations for all published documents is 4417. These 300 articles demonstrate 441.70 citations per year,while the average number of citations per author is 1602.11. On the other hand, papers per authoraverage 124.85, and authors per paper resultin3.35. This citation's metrics of the published documents illustrate that a significant number of researchers have raised the issue of learning poverty, looking at different angles of the needs and conditions of each of their countries and regions.

Table 1. Citations Metrics of Published Documents on Learning Poverty

| Metrics | Data |

| Publication years Papers | 2014-2023300 |

| Citation years | 10 (2014-2024) |

| Number of Citations | 4417 |

| Citations per Year | 441.70 |

| Citations per Paper | 14.72 |

| Citations per Author | 1602.11 |

| Papers per Author | 124. 85 |

| Authors per Paper | 3.34 |

| h-index | 31 |

| g-index | 59 |

Table 2 illustrates the Top 10 authors who actively contribute to learning poverty. The authors' contributions in the field strengthen the fact that learning poverty has been acentreof great academic interest, especially in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis. In academia, the number of citations related to an author acts as proof of their work both to be relevant and rich in information. In line with the statement, the table describes that the most cited authors with 520 total citations areKuhfeldet al. (2020), whose article isentitled “Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement”. Thus, the impact of the publication in the Journal of Educational Research within therelevant scope is quite significant, as it relates to the topical issue of how the pandemic-induced closure of schools may affectlearners’ performance. This work evidently resonated with the academic community,making a significant contribution to the discourse surroundingthe educational disruptions caused by COVID-19.

Hammerstein et al. (2021), witha total of 232 accumulatedcitations, take second place. The article “Effects of COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement: A systematic review”, published in a high-impact journal of Frontiers in Psychology, speaks to the extent of school closures on the negative effect on the learners’ achievement. It highlights the socioeconomic effectson families during the pandemic, where learners from low-income families experience negative effects thatneed to be mitigated. In comparison, Darling-Hammond and Hyler (2020) obtained an accumulated 217 total citations on the topic “Preparing educators for the time of COVID… and beyond”, published in European Journal ofTeacher Education speaks on the importance of addressing learners’ academic and social needs, to counter issues on learning loss as to prepare them for the uncertain conditions of teaching and learning, including distance learning, blended learning as well as in-classroom learning. The authors of this frequently cited article alsoemphasized the teachers’ role in supporting the social, emotional, and academic needs ofstudents.

Significantly, as described in Table 2 below, theremaining top 10 authors includedAzevedo et al. (2021) and Maldonadoand De Witte(2022), with total citations of 174 and 146, respectively. The authors focus on dimensions of learning poverty,including the pandemic's long-term repercussions, concerns about equity, and socioeconomic factors that act as determinants ofeducational inequalities. These are published works that range fromreputable publishers like the World Bank Research Observer and British Educational Research, which contribute to adiversified understanding of learning poverty. Moreover, an interesting observation from the analysis is the recurrence of theCOVID-19 pandemic's impacton education. The pandemic has undoubtedly acted as acatalyzingfactor, leading to increased research output on learning poverty, as observed in the thematic focus ofthe top-cited works.

Additionally, published articles from Kaffenberger (2021) and Martin-Donas et al. (2018), with 130 and 104 total citations, respectively, consider long-term effects, while some measure in-depth regarding the learning loss,as it aims to understand and address how the pandemic has affected and will affect education systems globally in both short and long terms.The information retrieved and highlighted is crucial for policymakers and educators to understand what interventions are necessary to help and support students duringthese unprecedented times. Moreover, the diversity in research themes and methodologiesamong top authors highlightsthe multifaceted nature of learning poverty. Itencompasses empirical projections of academic achievement loss, strategic analyses of educational policies, andthe fundamental diversities designed to mitigate the issues of learning poverty. Generally, the top 10 authors in this research areaonlearning poverty havemade significant contributions to the field and are widely acknowledged and cited by academicians, which can support future research in exploring thedeeper dimensions of learning poverty.

Table 2. Top 10 Authors on Learning Poverty

| No. | Author(s) | Title | Publication | Total Citations |

| 1. | Kuhfeld et al. (2020) | Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement | Educational Research | 520 |

| 2.. | Hammerstein et al. (2021) | Effects of COVID-19 related school closures on student achievement: A systematic Review | Frontiers in Psychology | 232 |

| 3. | Darling-Hammond and Hyler (2020) | Preparing educators for the time of COVID…and beyond | European Journal of Teacher Education | 217 |

| 4. | Azevedo et al. (2021) | Simulating the potential impacts COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates | World Bank Research Observer | 174 |

| 5. | Maldonado and De Witte (2022) | The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes | British Educational Research | 146 |

| 6. | Kaffenberger (2021) | Modelling the long run learning impact of the Covid-19 learning shock: Actions to (more than) mitigate loss | International Journal of Educational Development | 130 |

| 7. | Martin-Donas et al. (2018) | A deep learning loss function based on the perceptual evaluation of the speech quality | IEEE Signal Processing Letters | 104 |

| 8. | Gore et al. (2021) | The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: An empirical study | Australian Educational Researcher | 98 |

| 9. | Sparrow et al. (2020). | Indonesia under the new normal: Challenges and the way ahead | Bulletin of Indonesia Economic Studies | 89 |

| 10. | von Hippel and Hamrock (2019) | Do test score gaps grow before, during, or between the school years? Measurement artifacts and what we can know in spite of them | Sociological Science | 87 |

Co-occurrence Analysis

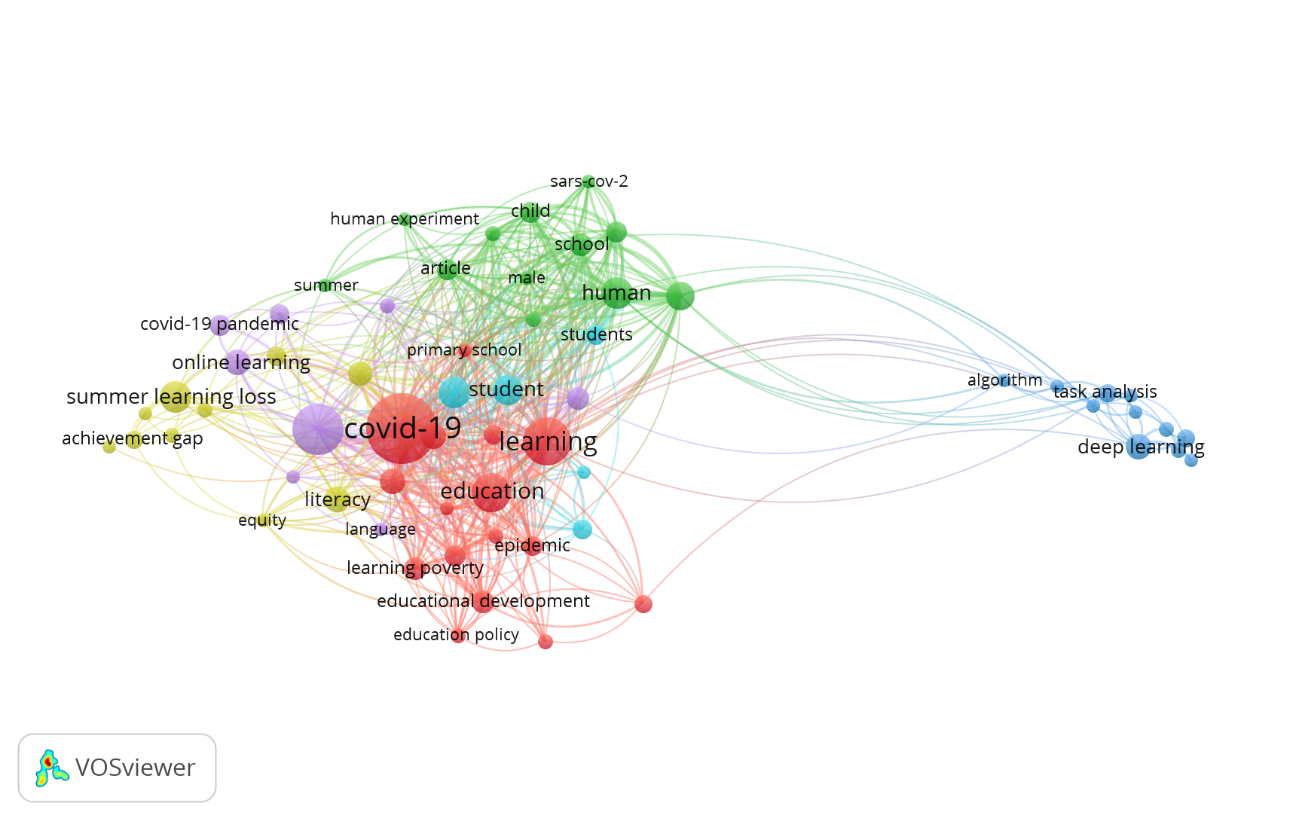

The result of the co-occurrence of all keywords in Table 3, encompassing 1373 keywords and 62 thresholds corresponding to six clusters, demonstrates the frequency and interrelation of keywords in research addressing learning poverty, thereby highlighting the principal themes and focal points of the discourse on the subject. A threshold of 62 was established to enhance analytical clarity by concentrating on the most significant and often occurring keywords while reducing interference from low-frequency terms (Martí-Parreño et al., 2016). This method facilitates the recognition of significant topic frameworks and research clusters. This is because overly low thresholds may result in fragmented or marginal keywords that do not significantly enhance the bibliometric mapping.

COVID-19 and pandemic:With the highest frequency of the keyword 'COVID-19' (n=93) and total link strength (n=263), alongside 'pandemic' (n=20) occurrences and (n=90) total link strength, COVID-19 has become synonymous with learning poverty. The predominant keyword signifies that learning poverty has become the primary focus of numerous scholars due to the swift transformations in schooling throughout the pandemic. The keyword"COVID-19" in notable research studies, such as those byTashtoushet al. (2023) and Kaffenberger (2021), underscores that learning loss can be observedfrom multiple dimensions, particularly in children's mathematical abilities and linguistic skills. The authors alsoemphasized the necessity of alleviating the problems and discerningthe mechanisms that effectively counteract the adverse impact of COVID-19 on children's academic performance. The study by Molnár and Hermann (2023)suggests that primary-level students experienced developmental delays due to extended school closures, as well as enduring academic deficits following the COVID-19 pandemic(Kuhfeldet al., 2020).

Leaning and learning loss:The term 'learning' appears 43 times with a total connection strength of 227, whereas 'learningloss'occurs 50 times with a total link strength of 107, highlighting critical factors during the pandemic that contributed to learning loss, such as students' lack of engagement and socio-economic challenges. The explanations for the causes of learning losses are apparent in previous studies by Haser et al. (2022) andKuhfeld(2019). The results indicate that learners from disadvantaged socio-economic backgroundsface challenges in sustaining their education in an unstable environment, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sonnenschein et al. (2021) found that children without structured learning at home experienced regression in reading fluency and comprehension.

Student and child:Learning poverty illustrates the progression of young learners in obtaining fundamental literacy skills, with thekeywords'student' appearing 17 times and possessing a total link strength of 107, alongside 'child', which occurs 9 times with a total link strength of 78, emerging as significant terms associated with learning poverty. Consistent with commonlyutilisedkeywords, the publications by Relyea et al. (2023) and Molnár and Hermann (2023) examined the effects on the reading proficiency of young learners aged 7 to 11 years regarding learning loss. The authorsemphasisethe significant adverse impact of COVID-19 on young learners, who were unable to make any progress during remote learning. Moreover, Downey and Condron (2016)emphasized that extended learning deficits disproportionately affect early primary pupils, especially in contexts lacking parental academic support.

Education and school:The term 'education' recorded 28 occurrences and 93 total link strengths, whereas 'school registered 10 occurrences and 78 total link strengths. This data illustrates the prevalence of these terms in research addressing learning poverty, asknowledge acquisitionprimarily occurs within the educational context of schools. According to the research conducted byAuriniand Davies (2021) and Sabates et al. (2021), the terms 'school’and 'education' indicate that during the pandemic, global education systems swiftly transitioned to more appropriate modalities, including online and remote learning, while implementing school closures as a strategy to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 and protect both learners and educators. Dougherty (2025) advocates for the continuation of in-person or hybrid instructional techniques. Likewise, Bell et al. (2019) showed that sustained school involvement during summer intervals significantly mitigates cumulative learning loss.

Academic performance:‘Academic performance’ is described as synonymous with learning poverty, with 12 occurrences and a total link strength of 68. Consistent with other ranked phrases, academic performance is often associated with terms connected to learning poverty, as it is a consequence. Alvarado et al. (2023) and O’Brien et al. (2023)found that, in response to COVID-19, students experienced a decline in academic performance, which negatively impacted their academic progress due to the challengingeducational environment. The research is corroborated by findings byHallinet al. (2022), which demonstrated delayed improvements in writing and comprehension abilities following the resumption of school during lockdown. The researchemphasizes that students with significant learning challenges who experience learning loss originate from diversecultural and linguistic backgrounds.

Poverty:A notable term indicative of learning poverty, 'poor' (n=13 occurrences) and (n=67 total link strength), underscores that learning poverty has exacerbated fundamental learning disparities based on learners' socio-economic backgrounds. Research conducted by Hevia et al. (2022) and Crouch et al. (2021) examines the educational disparities among individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds and the degree to which socioeconomic status can affect reading proficiency as a component of learning loss for these learners. Hevia et al. (2022) report that the educational inequality gap experienced by learners has exacerbated the school dropout epidemic. Furthermore,Jeonget al. (2023) investigated the nexus between poverty and remote learning contexts, determining that disparities in access exacerbated persistent educational inequities.

Table 3. Top 10 Frequently Used Keywords in Research Articles on Learning Poverty

| Rank | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | covid-19 | 93 | 263 |

| 2 | learning | 43 | 227 |

| 3 | learning loss | 50 | 107 |

| 4 | student | 17 | 103 |

| 5 | education | 28 | 92 |

| 6 | pandemic | 20 | 91 |

| 7 | school | 10 | 82 |

| 8 | child | 9 | 78 |

| 9 | academic performance | 12 | 68 |

| 10 | poverty | 13 | 67 |

Co-word Analysis

Cluster 1 (Red) – COVID-19 Impact on Learning

Cluster 1 has 16 keywords, including “academic performance,” “child development,” “COVID-19,” “education,” “learning poverty,” “school closure,” and “primary school.” The terminologyhighlights the impact of COVID-19 on global education systems, stemming from the swift school closures that disrupt traditionalteaching and learning methods. Thus, it increases educational inequities among students. Research byAuriniand Davies (2021) and Hevia et al. (2022)highlights the impact of the education crisis, encompassing school closures and remote learning difficulties, on learners' educational outcomes related tolearning poverty. It has been observed that inadequate access to technology and the internet has contributed to educational achievement disparities and learning poverty.

Cluster 2 (Green) – Educational Inequality and Learning Poverty

The 12 keywords, including “article,” “child,” “distance learning,” “pandemics,” and “schools,” pertain to the educational inequity and learning deprivation that arose from COVID-19, which hindered learners' attainment of fundamental numeracy and reading abilities. The disparity encompasses socio-economic issues, educational policies, and systemic disparities that profoundly affect the quality of education. Furthermore, the significance ofminimisinglearning barriers to enhance educational outcomes for families of lower socioeconomic status isemphasisedin research conducted by Crouch et al. (2021) and King et al. (2023).

Cluster 3 (Blue) – Online Learning and Digital Divide

Cluster 3 includes 11 keywords,such as “learning systems”, “performance”, “task analysis”, and “loss functions”, which describe the shift from traditional teaching and learning to online learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and consequently increase the digital divide amonglearners. In different areas of addressing digital technology and the digital divide,Timotheouet al. (2023) and Huntington et al. (2023) discuss the effectiveness of online learning on learners’ learning outcomes and how the usage of the technology crucially impacts learning poverty during the pandemic, which widens the educational gaps.

Cluster 4 (Yellow) – Young Learners and Social Factors in Learning

The keywords involve representing cluster 4 focuses on “achievement gap”, “early childhood”, “equity”, “mathematics”, “reading”, and “literacy”, which provide dimensions of learners’ way of learning, including the teachers, learners, and schools’ roles during the teaching and learning process.Unlike other clusters, this cluster places a crucial emphasis on the social factors that involve learners’ family background, school environment, and peer interaction, as central to influencing learners’ learning outcomes and contributingto the mitigation of learning poverty. Studies by Spiteri et al. (2022) and Relyea et al. (2023)highlight the importance of learners’ development at the start of their childhood as a means of emphasizing the psychosocial factors and school environment that influence their numeracy and literacy skills, particularly inreading achievement.

Cluster 5 (Purple) – Learning Loss and Educational Outcomes

Cluster 5, with 8 keywords, including “academic achievement”, “COVID-19 pandemic”, “learning loss”, “online learning”, and “school closures”, discusses learning loss synonyms for learners from low-income families at a particular time, widening the achievement gap and learning poverty.Kuhfeld(2019) and Bell et al. (2019) describelearning loss as involving both literacy and numeracy skills. Poor foundational skills in these areas hinder the acquisition of knowledge, ultimately affecting overall educational outcomes and contributing tolearning poverty.

Cluster 6 (Turquoise Blue) – Advanced Learning Technologies

Cluster 6comprises the remaining 5 keywords: “e-learning”, “pandemic”, “student”, “teaching”, and “students”, which are the least frequentlyused keywords among all clusters. This cluster, on the other hand,discusses the role of advanced technologies inpersonalisinglearning to improve learners’ educational outcomes and concurrently addressaspects of learning poverty. Research by Kwak et al. (2023) and Michieli et al. (2020) suggests that advanced technologies canoptimisethe learning processes and outcomes even during the pandemic COVID-19.

Table 4. Co-Word Analysis Cluster Label

| Cluster No and Colour | Cluster Label | Number of Keywords | Representative keywords |

| 1 (Red) | COVID-19 impact on learning | 16 items | “academic performance”, “child development”, “covid-19”, “education”, “learning poverty”, “school closure”, “primary school” |

| 2 (Green) | Educational inequality and learning poverty | 12 items | “article”, “child”, “distance learning”, “pandemics”, “schools” |

| 3 (Blue) | Online learning and digital divide | 11 items | “learning systems”, “performance”, “task analysis”, “loss functions” |

| 4 (Yellow) | Young learners and social factors in learning | 10 items | “achievement gap”, “early childhood”, “equity”, “mathematics”, “reading”, “literacy” |

| 5 (Purple) | Learning loss and educational outcomes | 8 items | “academic achievement”, “covid-19 pandemic”, “learning loss”, “online learning”, “school closures” |

| 6 (Turquoise Blue) | Advanced learning technologies | 5 items | “e-learning”, “pandemic”, “student”, “teaching”, “students” |

Figure 4. Co-word Analysis

Implications and Significance of the Analysis

The bibliometric analysisof learning poverty, focusing on numeracy and literacy amongyoung learners, is highly revealing in terms of critical insights into the present research landscape and offers notable implications for the education sector. Importantly, it provides an understanding of the challenges as the world responds to global crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, which necessitates informed and strategic interventionsto mitigate learning poverty.

Addressing Learning Poverty Post-Pandemic

This analysis reveals the extensive impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on global educational attainment. The epidemic has disrupted conventional educational methods and exacerbated existing disparities in schooling, particularly regarding learners' core literacy and numeracy skills. In India, the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER) 2022 indicated that the proportion of Grade 3 kids capable of reading at a Grade 1 level decreased from 27.3% in 2018 to 20.5% in 2022, exemplifying significant learning regression attributable to school closures.Kuhfeldet al. (2020) estimated a possible 30% to 50% reduction in mathematics learning gains in the United States as a result of extended remote instruction.

To mitigate such reductions, nations like Chile have established focused remedial programs, such as PlanAprendoenCasa, which integrate printed educational resources, television courses, and radio broadcasts to engage pupils lacking internet access. These methodologies illustrate that resilient, multi-platform techniques can function as effective measures for learning recovery. Additionally, enhancing teacher proficiency via professional development initiatives in online pedagogy, exemplified by Singapore’s National Digital LiteracyProgramme. It is regarded with utmost seriousness, since it is crucial for maintaining continuity and efficacy in hybrid and emergency learning contexts.

Research byAuriniand Davies (2021) and Hevia et al. (2022) illustrates that prolonged school closures have significant repercussions, hence underscoring the necessity for extensive and focused interventions to prevent more damage. These findingsunderscore the need for educational systems to implement comprehensive interventions that encompass remedial education programs, mental health support, and policies to address the disparities exacerbated by the pandemic. The analysisemphasisesthe necessity of cultivating resilient and flexible educational systems for implementation during periods of global instability.

The rapid shift to e-learning revealed significant disparities in access to digital resources, as demonstrated byTimotheouet al. (2023) and Huntington et al. (2023). Moreover, future educational policies must guarantee that every student has the requisite skills and resources to fully engage in their education, irrespective of their background. This encompasses technology with internet connectivity, as well asany necessary training for educators to deliver effective online instruction.

The Role of Educational Equity in Combating Learning Poverty

The bibliometric study revealed that educational equity is a significant theme that indicates systemic impediments and sustains learning poverty. Learning poverty becomes a component of broader socio-economic disparities examined by Crouch et al. (2021) and King et al. (2023). These issues necessitate comprehensive solutions and must be implemented not only inside educational institutions but also at higherorganisationallevels and within the family environment. The policy must be structured to facilitate access to teaching and learning, ensuring that children from diverse circumstances can attain quality education.

In South Africa, students from rural and low-income households encountered significant instructional loss due to unequal access to devices and connectivity. The Western Cape Education Department implemented zero-rated educational websites, allowing access to digital information without data charges, exemplifying a policy designed to bridge the digital divide. Designated funding for schools in underprivileged regions, support initiatives for at-risk children, and inclusive educational policies that address the varied needs of all learners are integral components of the solutions aimed at achieving educational fairness.

Given the significant stakes in achieving educational equity, educational systems can successfully establish opportunities that guarantee individual achievement by tackling the fundamental causes of learning poverty. Thus, it would affect not just individual lives but also contribute more broadly to society, namely in terms of economic development and social cohesiveness.

Leveraging Technology to Improve Learning Outcomes

The data also demonstrates the increasing interest in the application of sophisticated learning technologies, such as artificial intelligence andpersonalisedlearning platforms, to address deficiencies in education.These technologies possess significant potential to influence educational outcomes, particularly inreading and numeracy (Kwak et al., 2023). AI-driven educational platforms, such asMATHia, have been implemented in U.S. schools to tailor training according to students' performance in real-time, enhancing numeracy skills for at-risk learners (Institute of Education Sciences,n.d.). The Kolibri platform, developed by Learning Equality, offers offline digital content aligned with local curriculum in refugee camps in Kenya and Uganda (Nanyunja et al., 2022). This intervention illustrates the adaptability of technology in low-resource settings, enabling educators to address literacy disparities.

Furthermore, it is a tool that offersindividualisedlearning experiences and can thus beutilisedto detect individual students' needs and treat them more effectively than conventional methods. Nonetheless, the analysis indicated that there is potential to exacerbate current inequities. The practical implementation of educational policy from an equity perspective necessitates the fair allocation of technological resources and enough assistance required for achievement. In Bangladesh, fewer than 40% of students were able to participate in online classrooms due to a lack of devices,according to BRAC’s 2021 study (BRAC International, 2021). Therefore, the equitable implementation of educational technology tools, in conjunction with offline options such as printed materials and community radio, is imperative. Therefore, it is essential for educational policy to ensure that the benefits of new learning technology are disseminated to all socio-economic classes within society. This is necessary to diminish the extent of learning poverty and guarantee that everyone benefits from improvements in technology.

Implications for Future Research and Policy Development

Longitudinal studies on learning poverty are essential for monitoring its impacts over extended periods, particularly in light of theCOVID-19 pandemic's repercussions. Such research would provide data on the efficacy of various interventions and guide future educational strategies. There is an acknowledgement of the need for interdisciplinary approaches to tackle learning poverty. The complexities of learning poverty are multifaceted; thus, collaboration with disciplines beyond education, including sociology, psychology, and technology, is essential. The interdisciplinary approach to study enhances the likelihood of inclusive and practical solutions. In conclusion, the educational disruptions caused by the pandemic have highlighted the need for systems to be prepared for continuity in the event of another crisis, necessitating the development of contingency plans for emergency remote learning. This requires ensuring that their systems are sufficiently flexible and resilient to adapt to evolving circumstances.

Conclusions

This bibliometric analysisoffers a comprehensive overview of the global research landscape on learning poverty from 2014 to 2023, with a focus onliteracy and numeracy development in young learners. The results indicate asignificant increase in academic focus followingthe emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, which profoundly disrupted educational systems and exacerbated existing learning disparities. The co-occurrence and co-word analyses validate that the primary study themes focus on pandemic-related school closures, the digital gap, educational inequality, and innovative technological solutions. The analysisemphasisesthe necessity for education systems to adopt targeted, equity-oriented policies and initiatives that tackle the fundamental causes of learning poverty. The incorporation of practical remedies, including remedial training, zero-rated digital platforms, and AI-drivenpersonalisedlearning tools, illustrates the existence of scalable and context-sensitive strategies to facilitate recovery and resilience.

Moreover, the studyemphasisesthat learning poverty is not merely an educational concern but one that links with wider social, economic, and technical frameworks. Consequently, sustainable solutions necessitate interdisciplinary cooperation and comprehensive policy frameworks that address inequalities in access, preparedness, and educational opportunities. Theintegration of evidence-based digital solutions with inclusive pedagogy and infrastructural support presents a promisingtrajectory for advancement. Subsequent research should leverage bibliometric insights to pinpoint research deficiencies, examine the long-termeffects of treatments, and develop resilient systems capable of withstandingfuture disruptions.Utilisingboth scholarly research and practical advancements, worldwide initiatives to eradicate learning poverty can become more focused, inclusive, and sustainable—ultimately aiding in therealisationof SDG 4: Quality Education for All.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

No ethical approval was sought as the article does not present any study of human or animal subjects.

Data sharing is not applicable, as no new data were created or analyzedin the presented study.

Generative AI statement

The authors used ChatGPT to enhance the clarity, structure, and descriptive quality of the manuscript in order to meet academic standards. Following the use of this AI tool, the authors thoroughly reviewed and verified the final version of their work. The authors take full responsibility for the content of the published manuscript.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Yob: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments;Analysedand interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data; Wrote the paper. Pek: Conceived and designed the experiments;Analysedand interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools, or data. Mee: Proofread and formatted the paper to match the journal requirements. Von: Proofread and formatted the paper to match the journal requirements.Nallisamy: Performed the Analysis usingVOSviewerand worked on the formatting. Henry:Analysedand interpreted the data. Camara:Analysedand interpreted the data.