Introduction

The Hungarian Context of Dual Language Education and Bilingualism

Public education in Hungary offers more than 300 dual-language programs in primary and secondary schools. Since the launch of modern bilingual schools in the late 1980s – considered a major reform attempt at the time – there has been a steady expansion in numbers (of programmes and enrolled students), spatial distribution, and popularity. Four decades of changes in socioeconomic conditions, demographic patterns,language and educational policy priorities, and regional development have led to the emergence of bilingualism in various school types and languages of instruction. This diversity is one of the most valuable but often overlooked achievements of the Hungarian education system.

As of 2025, more than 120 secondary schools offer dual language education in 11 languages other than Hungarian,primarily in the forms of bilingual and nationality programs, with a smaller number of programs following a range of international curricula. These programmes are still regarded as attractive options for modern language learning, offering high added pedagogical value that enhances school prestige and contributes to a stable demand from the local community, as well as the ability to enroll students from a wider sphere of influence. Currently, tens of thousands of students are studying in a form of education where certain subjects are taught in a language other than Hungarian (Kapusi, 2024a; Kovács, 2018; Vámos, 2017).

In this study, the term “dual language education” is used to refer to all bilingual, nationality (minority) and international secondary school programmes (for students aged 14-20) in which teaching is concluded in two different languages and certain subjects are taught in a foreign language (L2) other than Hungarian, regardless of the students' mother tongue (Table 1). The given language can therefore be the target language, the mother tongue (e.g. in minority education) and the language of instruction corresponding to the selected curriculum (in international schools).

Table 1. Comparison of Dual Language Secondary School Programmes in Hungary (Kapusi, 2024b, Revised)

| Type Of Dual Language Programme* | Bilingual | Nationality | International |

| Aim Of Programme | Enabling wide access to the learning world languages | Promoting national languages and maintaining the cultural identity of ethnic minority groups | Providing access to high-quality education based on international standards and a foreign curriculum |

| Language Of Teaching | English, French, German, Italian, Russian, Spanish, Chinese | Croatian, German, Romanian, Serbian, Slovakian | English, French, German |

| (Other Than Hungarian) | |||

| Type Of Secondary Schools With Dual Language Programmes | both in secondary grammar schools and vocational secondary schools | Only in general secondary grammar schools | In general secondary grammar schools and purpose-built international schools |

| Number Of Subjects Taught In Foreign Lang. | 3-5 subjects in most schools | At least 50% of the subjects | All of them |

| (except for L1, L2, etc.) | |||

| Curriculum | Hungarian | Hungarian | British, American, Austrian, German, French, international (IB) |

| Administration / Regulation | State (with a few privately funded grammar schools) | state | private |

| (but: intl. programmes in 2-3 state schools are tuition-free) | |||

| Location | Decentralised network (every county, Budapest, several towns) | Budapest + smaller towns in areas with a higher % of ethnic minorities | Budapest + two regional centres (Debrecen, Győr) |

| Number Of Programmes (2010-2025) | 140** | 17 | 18 |

| Geography Textbooks Available In The Foreign Language | Very limited / partially available (depending on the language), mainly imported or adapted by teachers | Partially available | Available in all schools, |

| (translated versions of Hungarian textbooks or imported from abroad) | written specifically for the given educational programme / curriculum | ||

| Foreign Language Geography Teachers | Almost all Hungarian speakers with 2-3 native speakers | Mainly native speakers | Both native and non-native speakers of the language of teaching |

| or teachers belonging to the same ethnic minority | |||

* Note: Certain schools offer dual language programmes in two or more foreign languages. In addition, a few schools run two programmes (bilingual and international, bilingual and nationality) under the same roof.

** Note: Numbers tend to fluctuate due to newly launched or recently abandoned programmes.

Bilingual programmes– the most widespread ones – are designed to enable the acquisition of a world language in a relatively large bulk of lessons (including 3-5 subjects) concluded in L2. In nationality education – more typical in regions with higher ethnic diversity –, the primary goal is to preserve, maintain, and promote the culture and identity of ethnic minority groups. In international programmes, language learning is realised across every segment of education (e.g., learning subject content in foreign languages, native-speaking teachers, an international student community, authentic textbooks, and extracurricular activities), with less attention to teaching the target language separately, except for those students who require scaffolding. In general, most students in dual language programmes in Hungary are non-native speakers of the target language.

The Role of Geography in Dual Language Programmes

As presented in Table 1, the practice of teaching Geography in L2 has been present in all three types of programmes for decades. Yet, there are significant differences in how Geography education is realised, mainly content-wise: while the subject content taught in bilingual and minority education is determined by the national curriculum, Geography teaching in international programmes takes place in accordance with the traditions of foreign curriculum and is not subject to any domestic content framework regulations or requirements (Kapusi, 2021a, 2024b). In Hungarian public education, Geography is a mandatory subject. As bilingual and nationality programmes fall under the Hungarian regulations, the only choice they have is whether they offer Geography in Hungarian or in L2. In international programs, Geography is often optional for students, depending on the curriculum, and is always taught in L2.

Geography was already among the subjects recommended and designated for foreign language teaching and learning when the first bilingual secondary schools were established, meaning that the practice of teaching Geography in a second language spans more than three decades (Vámos, 2017; Vámos & Kovács, 2008). With the expansion of bilingualism across the education system, Geography has managed to maintain its role as a key subject in the majority of programs, despite the challenges the subject – and science education in general – has faced over the years (Kapusi, 2025). As of 2025, Geography is still a common choice all around the dual language school community: it has been taught in all foreign languages (with the exception of Chinese) and is still the most popular optional final exam subject (Kapusi, 2021b, 2022), both in Hungarian and in L2.

Geography is a subject that links various fields of natural and social sciences. By teaching and learning it in L2, this unique interdisciplinary role is enriched with a valuable linguistic dimension (Eurydice, 2006; Heidari et al., 2022). In foreign language Geography lessons, geographical and linguistic competences are developed simultaneously, complementing and reinforcing one another (Bognár, 2005; Kapusi, 2024b; Kárpáti, 2024). As a result of the complex integrated use of Geography and language teaching methods, students become capable of mastering subject content and acquiring knowledge in L2, consciously using the foreign language as an instrument to develop a deeper understanding of geographical processes.

Despite several attempts and efforts to modernise the methodological approach and content, the status of Geography as a subject and discipline has been steadily weakening in Hungarian education. The declining number of lessons in recent years has directly contributed to the erosion of the prestige of subject-specific competences, leading to an increasing number of people questioning the relevance of Geography in particular (Csorba, 2017; Neumann, 2021;Seres &Makádi, 2022). The shortage of science teachers in primary education and the recent shifts in educational policy (including the dropping of Geography as a subject from several vocational secondary schools) have also exacerbated these issues.Many Hungarian students complete secondary education without receiving any meaningful Geography education to rely on. In dual language programmes, these difficulties of subject teaching are often compounded by the challenges of teaching and learning the subject in a second language L2.

Content and Language in Geography Education

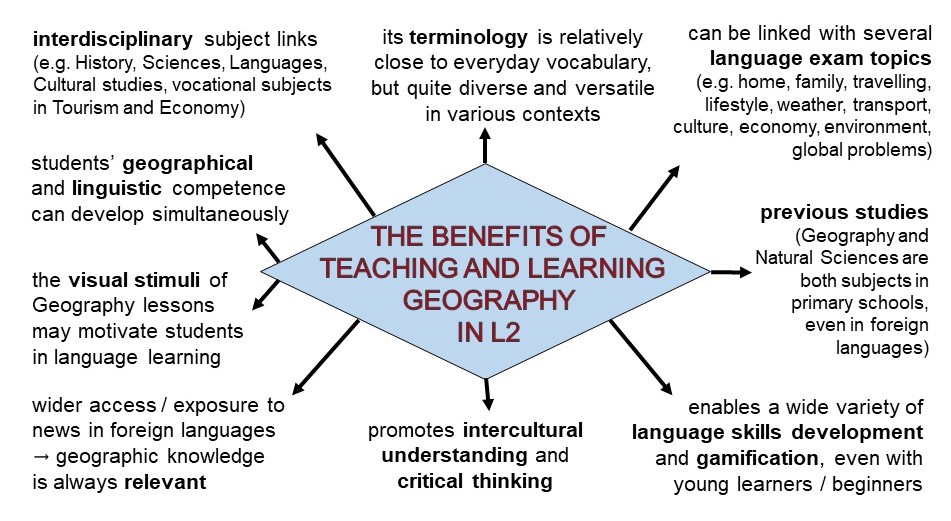

There are numerous benefits of learning Geography in foreign languages (Figure 1). Its vocabulary aligns closely with everyday language use, making subject content more accessible even to younger or less skilled L2 learners. Basic vocabulary is already familiar to students before they begin learning Geography in L2 (Kapusi, 2024a, 2024b;Zaparucha, 2007), with geographical topics appearing in English and German language coursebooks quite extensively. In comparison to other natural science subjects, the subject-specific language content of Geography is considered easier to absorb. Certain geographical units can be mastered even with a relatively low level of language proficiency, partly explaining why this subject is a common choice for teaching in L2 in dual-language primary school programs (Kapusi, 2024b). As a consequence, it provides opportunities for diverse and flexible language development, which, combined with the visual stimuli of the subject, can create a highly motivating learning environment in which students can engage with both the subject and the language simultaneously. However, most content teachers are not specialists of the target language (Zaparucha, 2007) who find it hard to identify students’ language demands intertwining content and language successfully (Heidari et al., 2022; Morawski & Budke, 2017) and who have difficulties in the implementation of CLIL (Bakti & Szabó, 2016).

Figure 1. Benefits of Teaching and Learning Geography in Foreign Languages (Self-edited)

Due to the steadily declining prestige of geographical knowledge and the significant disparities among primary schools, the pool of secondary school students enrolled in dual language programs is becoming increasingly diverse, not only in terms of language competence but also, unfortunately, in terms of subject-specific literacy. The lack of basic knowledge and general interest in Geography is often exacerbated by the difficulties of learning it in a second language. Previous experiences in both subject and language learning can greatly influence student motivation in both directions (Vámos, 2017; Vámos & Kovács, 2008). Students with weaker language skills are often more motivated to overcome their language barriers; therefore, they perform better and more consistently in subject learning than those students who feel more comfortable with their stronger foundations in L2 and show less interest in learning subject-specific terminology.

In addition, the thematic structure of the Hungarian Geography curriculum offers several links to a wide range of other subjects, including all natural sciences, History, Cultural studies, or even Vocational studies in Tourism or Economics. Still, linking Geography with other subject contents is often the result of coincidence generated by the incoherence and misalignment of subject curricula rather than planning. For instance, certain themes in Geography appear in the curriculum earlier than when students are supposed to acquire the relevant historical knowledge necessary for the understanding of the given geographic theme (e.g., the historical context of space research, the establishment of the EU, or the emergence of globalisation and international organisations). In addition, geographical themes also appear in multiple language exam topics, which can be effectively exploited in higher grades when exam preparation becomes a priority.

Learning Geography in a second language L2 broadens students’ horizons in both subject competence and language proficiency. In a dynamically changing globalised world, geographical awareness and language communication skills are considered particularly relevant. Increasing linguistic diversity and the density of global interactions both underline the relevance of Geography education in different languages (Piotrowska, 2007), providing a very rich and diverse input of topics and lexical items to be harnessed in a variety of L2 learning environments. However, its true added value lies in the wide array of options by which disciplinary literacy and transferable skills could be developed (Bakti, 2023). The success of learning strategies and skills associated with Geography learning in L2 can boost student motivation to delve into other content in L2 (or even L3) with greater confidence and efficiency,providing an advantage in higher education and the increasingly international labour market (Piotrowska, 2007). The subject-specific language of Geography is key to a higher-level understanding of geographical issues (Morawski & Budke, 2017), and also makes new channels of knowledge more accessible to students, promoting intercultural understanding — a conceptual cornerstone of CLIL pedagogy in any subject.

The primary aim of this research is to explore teachers' perceptions of the role of L2, language teaching, and CLIL within the daily practice of foreign language Geography teaching in Hungarian dual-language secondary schools. The study investigates the alignment of content knowledge and language skills development goals through the lens of Geography, one of the most common subjects taught in foreign languages.

Literature Review

There is no specific theory regarding the teaching and learning of Geography in L2 in international or Hungarian research papers. The majority of research discusses Geography in the context of bilingual education as one of the most common subjects to teach in L2 (Donert et al., 2008; Eurydice, 2006). Therefore, any theoretical framework applied within the discussion of foreign language Geography education needs to incorporate the underlying theory and models of CLIL (including the four Cs and the language triptych), addressing the interconnectedness of content knowledge and language learning objectives (Coyle et al., 2010; Coyle & Meyer, 2021; Nikula et al., 2016; Pérez-Cañado, 2011;Villabona &Cenoz, 2021).

Recent academic interest in the conceptualisation of cognitive discourse functions and subject-specific (or disciplinary) literacy (Bakti, 2023; Dalton-Puffer et al., 2024; Hüttner, 2024) also deepens the understanding of language and content integration as they explore the cognitive processes related to the acquisition of subject content and the subject-specific thinking and communication skills that students need to master when studying different academic disciplines.

As CLIL programmes across Europe tend to greatly differ in terms of implementation, several practices of content and language integration exist (Eurydice, 2006; Pérez-Cañado, 2011). As a result, a large collection of case studies and good practices has been published to explore how bilingual education and CLIL are realised in different educational systems and to what extent it has become integrated in teacher training.

Regarding the Central-Eastern European educational context, there is a number of publications exploring different aspects of Geography teaching, bilingual education and CLIL in Germany (Morawski & Budke, 2017), Poland (Byca, 2011;Czura &Papaja, 2013;Piotrowska, 2007;Zaparucha, 2007), Czechia (Chmelařová, 2017), Slovakia (Menzlová et al., 2020), and Serbia (Lazarević, 2019;Timotijevic et al., 2023). These studies reveal a deeper embeddedness and a more transformative role of CLIL pedagogy in education systems, offering a wider provision of theoretical and practical support for teachers to rely on.

For instance, in the Polish education system – which has traditions in bilingual education nearly as long as in Hungary –, foreign language Geography teaching has been quite common in middle and high schools (Byca, 2011), with coursebooks translated into English (Zaparucha, 2007) and specific CLIL models introduced in English, French, German and Spanish (Czura &Papaja, 2013). However, in Czechia, CLIL is adopted mainly at the primary level, but not really pursued by secondary schools though this level of education seems ideal for CLIL (Chmelařová, 2017). Bilingual education in Serbia is even more limited, with a wider set of challenges, including the lack of teaching tools and materials and overcrowded classrooms (Lazarević, 2019). Due to the vastly different educational systems and Geography teaching traditions, these regional case studies are not always relevant when the Hungarian context is examined, but research findings presented in this article resonate with those of the regional case studies at many points.

CLIL programmes have been steadily increasing in both Hungary and its neighbouring countries over the years. It is important to note that out of the three types of dual language education discussed above, CLIL is most often realized in bilingual programs, and most research in this field identifies CLIL with bilingual schools as well. However, no previous or current framework document (e.g., national curriculum) contains any explicit references, models, objectives, or expectations on how content and language integration should be implemented in schools. As guidelines and methods associated with CLIL are only vaguely implied, they have not been integrated into the textbook development (Kapusi, 2025). Only a few teacher training centres offer courses specifically designed for content and language integration, primarily focusing on early primary education – partly explaining why specific CLIL-based curricula exist in some bilingual primary schools only (Bakti & Szabó, 2016; Kovács, 2018; Sherwin, 2021;Trentinné Benkő, 2014).

While CLIL has been generating a steadily growing volume of academic research, in the Hungarian context, this discussion has remained predominantly language-oriented, focusing on cognitive, linguistic, and pedagogical aspects of bilingualism rather than subject-specific studies (e.g., Geography). These sources primarily explore the theoretical concepts of bilingual education (Kovács, 2018; Kovács &Vámos, 2007;Trentinné Benkő, 2014, 2016; Vámos, 1998, 2007, 2009, 2017; Vámos & Kovács, 2008), the cognitive aspects of bilingual education (Kisné Bernhardt, 2012;Várkuti, 2010a, 2010b), and the practical implementation of CLIL (Bakti & Szabó, 2016; Bognár, 2000, 2005; Mihály, 2009; Sherwin, 2021). A number of publications examine foreign language subject teaching from the perspective of a given language of instruction or institutional practice (Doró, 2005;Federmayer, 2005;Gálné Mészáros, 2007;Márkus, 2007; Papp, 2023; Pelles, 2006), but do not explore the situation of Geography as a subject in detail.

The teaching practice and challenges of CLIL in Geography lessons have been barely researched, therefore relevant studies are limited to a few recent articles (Bakti, 2023; Kapusi, 2021a, 2021b, 2024a, 2024b, 2025; Kárpáti, 2024; Katona & Farsang, 2012) and a selection of university theses, which focus on one aspect of teaching Geography in L2 (e.g. subject-specific vocabulary teaching, curriculum development or teaching aids), but were not developed into research publications (Kaplár Fehér, 2006;Kis, 2015; Paja, 2019; Pethő, 2005). As the extent of academic interest is quite limited, the values and achievements of foreign language subject teaching remain technically invisible (Hüttner, 2024; Kapusi, 2024a).

Methodology

This research was aimed at exploring aspects of content and language integration, content-language ratio, L2 exposure and CLIL awareness in secondary schools. Teachers with past and present experience of teaching Geography in languages other than Hungarian were invited to participate.

Participants

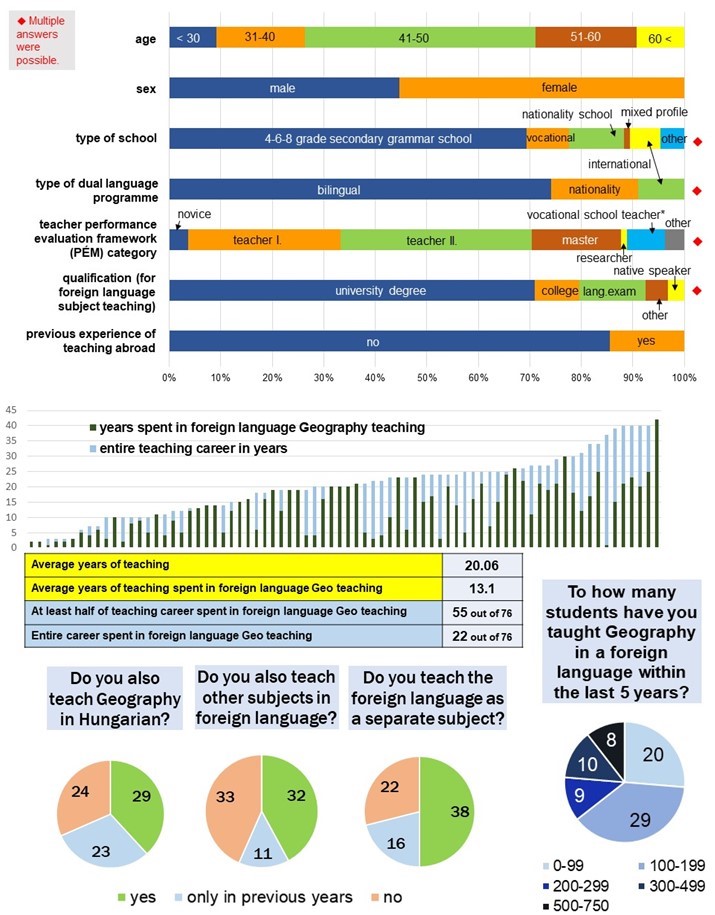

76 teachers participated in the research, representing all counties and major towns with dual-language secondary schools. While the majority of respondents represent bilingual secondary grammar schools, teachers from vocational schools and nationality education also participated, providing a wider spectrum across the Hungarian education system. 11 teachers had teaching experience in two different programmes. The spatial distribution of respondents across the country provided a balanced insight into dual language education in general. Around 70% of the potentially available teachers were willing to participate, which is considered to be a fairly high survey response rate in any public education research, and much higher than previously expected (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Overview of Respondents’ Teaching Career and Experience (Kapusi, 2024b)

As for the language of teaching, 59 respondents teach in one of the two most dominant foreign languages (32 in English, 27 in German, with 1 teaching in both), while 17 respondents teach in other languages (9 in French, 4 in Italian, 2 in Spanish, 1-1 in Serbian and Croatian). The survey was concluded in Hungarian, but questions were offered in English to those native speaking teachers who did not have a command of Hungarian to understand the initial survey. However, in a number of schools where Geography has been taught by native speakers, this approach did not work either. There were no available respondents who teach Geography in Slovakian, Romanian, and Russian, as those schools are no longer able to offer the subject in foreign languages due to the shortage of teachers. The large share of German can be justified not only by the presence of the language in bilingual, nationality, and international programmes, but by a strong and active teaching community with a number of common projects and communication platforms not typical of Geography teachers of any other L2.

Two-thirds of the surveyed teachers have – or used to have – teaching experience in Geography in Hungarian, as well. Those with experience of teaching L2 as a separate subject make up nearly the same share of the community. 11 teachers also teach other subjects, such as history, biology, or cultural studies. At the time of the survey, teachers had an average of 20 years of teaching experience with 13.1 years spent teaching Geography in L2. This detail, together with the number of students taught, also supports the rationale that there is a huge bulk of teaching experience to rely on regardless of age, location, type of programme or language of instruction.

Data Collection

All teachers were invited to complete a structured Google Form questionnaire on their perceptions and experience concerning the use of L2 and CLIL awareness within their daily practice of foreign language Geography teaching. The questionnaire consisted of several multiple-choice and open-ended items, allowing participants to share as much personal experience as they liked. The survey was designed to serve as a self-reflection tool, in which teachers were expected to share practical details and personal experiences.

The survey was preceded by the compilation of a previously missing database containing names of dual language schools and contact information for teachers involved in Geography teaching in L2. Potential participants were approached directly via email, registered in this database, or through their schools and fellow colleagues also involved in the research. The database has been updated since then, serving as the source of the mailing list still in use for communication among the teachers.

Data collection was concluded during the 2023-24 school year, preceded by a brief pilot phase in the summer to validate the survey and make necessary modifications to the phrasing of certain items, as recommended by fellow teachers invited to participate in the questionnaire testing. Survey responses were coded according to sub-topics, including professional experience, school type, language use, classroom practices, teaching resources, CLIL awareness, and general questions regarding dual language education. Responses for each survey item were aggregated for analysis, but were also examined separately (e.g., by school type and L2) to explore unique patterns and anomalies.

The main survey was followed by a more informal data collection with a smaller number of participants. These methods included school visits, exchanges at events (e.g., teacher conferences), video chats, and email exchanges of questions and answers. Although these respondents initially rejected – or were unable – to participate in the wider, more detailed research for personal or professional reasons, they could still be persuaded to share their experiences in a shorter, less structured form. The insights gained through these brief exchanges have been integrated into the dataset, adding depth to the analysis presented below.

Research Questions (RQs)

Findings are discussed separately, responding to the research questions listed below.

RQ1: Is it the language teacher’s or the content teacher’s attitude that dominates their daily practice?

RQ2: What patterns of L2 use are typical in foreign language Geography lessons?

RQ3: What are the most typical classroom methods and practices of teaching subject content in foreign languages?

RQ4: To what extent are language teaching methods integrated into subject lessons?

RQ5: Are teachers aware of CLIL? If yes, how well is CLIL incorporated into their daily practice? To what extent is CLIL pedagogy expected and realised in classrooms?

Findings

Perception and Attitude (RQ1)

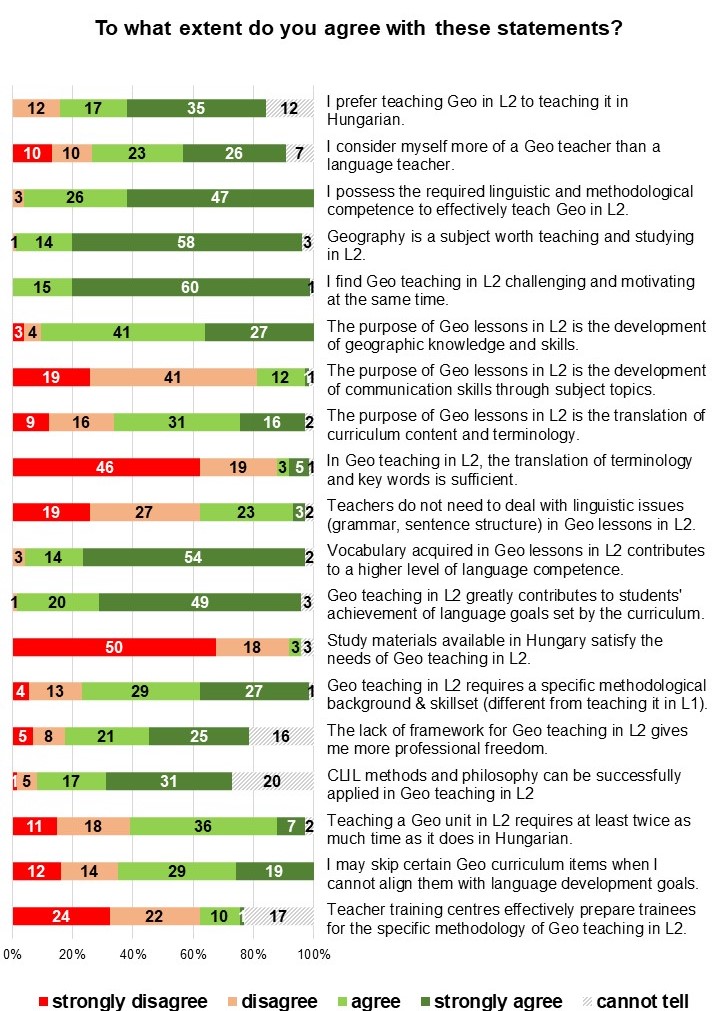

Teaching subjects in L2 requires a balanced combination of subject-specific content and methodology with language skills development. This dual focus is supposed to enhance geographical knowledge and language acquisition – and consequently, a higher level of disciplinary literacy (Bakti, 2023; Hüttner, 2024). Therefore, teachers are expected to possess both subject proficiency and language teaching competence simultaneously. In the case of 64% of the respondents, the Geography teacher’s attitude is more dominant (Figure 3). Nearly all respondents find foreign language Geography teaching challenging and motivating, with many of them actually preferring it to teaching the subject in Hungarian. These opinions also indicate that most teachers do not find these roles conflicting, but rather complementary.

Figure 3. Respondent Perceptions on Teacher Roles and Geography Teaching in L2

According to almost 90% of the respondents, the purpose of Geography lessons in L2 is the development of subject knowledge and skills rather than the development of communication skills embedded in geographical units, regardless of how committed teachers are to meeting the goals of language teaching. Teachers clearly reject the assumption that the purpose of the lessons would be reduced to merely introducing subject-specific terminology. However, a slight majority still believes that the purpose of Geography lessons in L2 is the translation of curriculum content into a foreign language.

This contradiction can be easily explained by the fact that all curriculum content (including the topical breakdown of key terminology and exam requirements) is published in Hungarian only, forcing teachers to translate or adapt these details into L2, which is a constant source of discrepancies in lexical items used in L1 and L2. There is consensus among the respondents regarding the usefulness and flexibility of geographic vocabulary and its impact on the language proficiency expected by the end of secondary education, supporting the assumptions on the benefits of Geography teaching discussed above.

L2 Use in Lessons and Code Switching (RQ2)

Survey findings reveal a typical dilemma concerning the extent and depth of language teaching within subject lessons in L2. As seen in Figure 3, 60% of the respondents do not tend to pay attention to practicing grammatical structures (e.g., tenses, sentence structure, word formation, phrasal verbs, linking words) in their Geography classes. This may stem from the perception that Geography teachers are solely responsible for the subject regardless of the language of instruction, while the acquisition of linguistic structures should take place in the general language classes. Due to the low number of subject lessons, teachers rarely go beyond the curricular framework in order to teach new grammar or practice specific aspects of the language itself – in fact, they cover less content. This is also confirmed by the majority opinion that the coverage of a given unit or topic requires at least twice as many teaching hours in L2 as in Hungarian.

The lack of attention to language can also be explained by the fact that most students have already acquired the linguistic competence necessary for learning subjects in L2 – identified by respondents as A2-B1 levels of the CEFR – by the time they begin their L2 Geography studies. Therefore, teachers do not see the need to sacrifice any of their already low number of classes specifically for language practice. As a result, coordination between Geography teachers and language teachers appears to be more accidental than planned or regular, although the survey revealed a few good practices, especially in the case of smaller languages and schools with a stronger reliance on teachers working together.

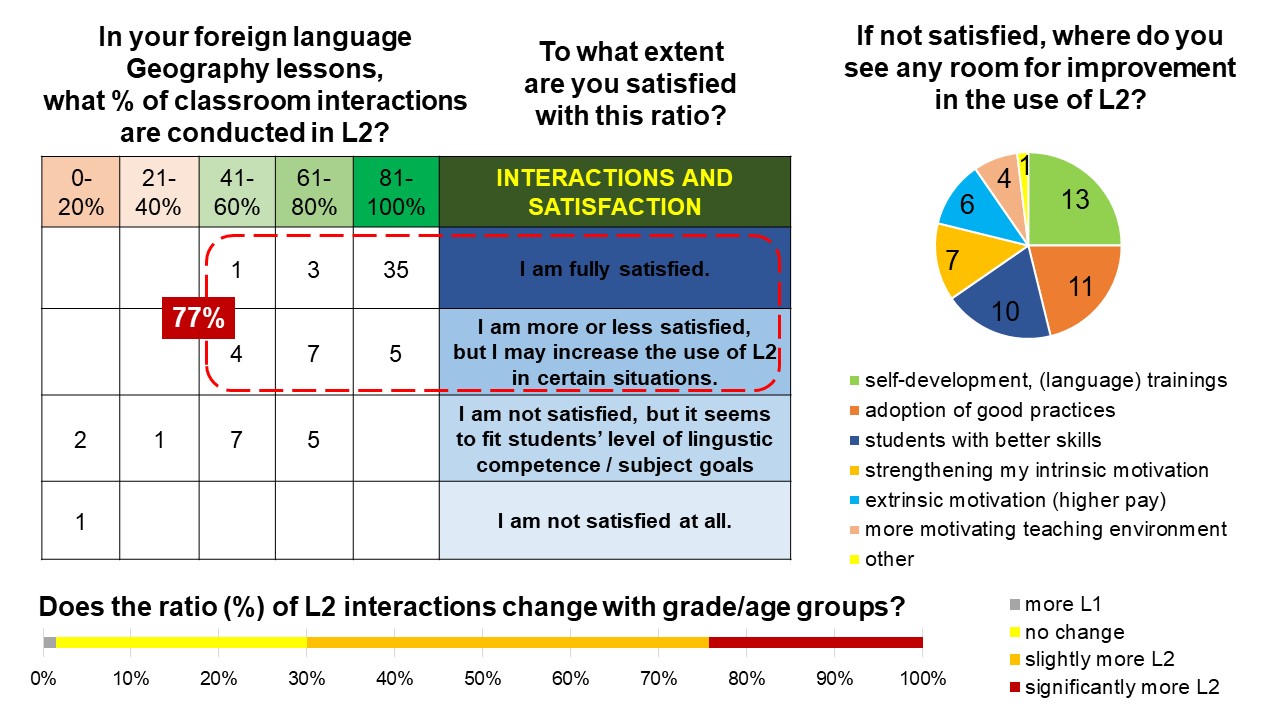

The vast majority of respondents strive for the greatest possible proportion of interactions in Geography lessons to take place in L2, and they are generally satisfied with this ratio of L2 use, even if it is lower in percentage (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The Use and Ratio of L2 in Classroom Interactions

The relationship between the languages of instruction and the ratio of language use is interesting. For teachers of English and German, the variance between the language use categories is quite significant, while in the case of languages for which there is no previous primary school experience (e.g., Italian), the lower ratio is more common. Respondents would typically expect an increase in the ratio of L2 use resulting from self-education, language training, and the adoption of good practices; however, the desire to strengthen the motivation level can also be identified in the answers. Although intrinsic motivation is vital to professional development, the hope of a better working environment or higher pay would also encourage teachers. Several respondents identified the elimination of the previously existing language allowance (given to teachers who teach subjects in L2) as a major problem, as well as the absence of training courses and the inclusion of less competent students, reinforcing the assumption that it is much more difficult for a student to learn subjects successfully in L2 if basic cognitive skills are lacking.

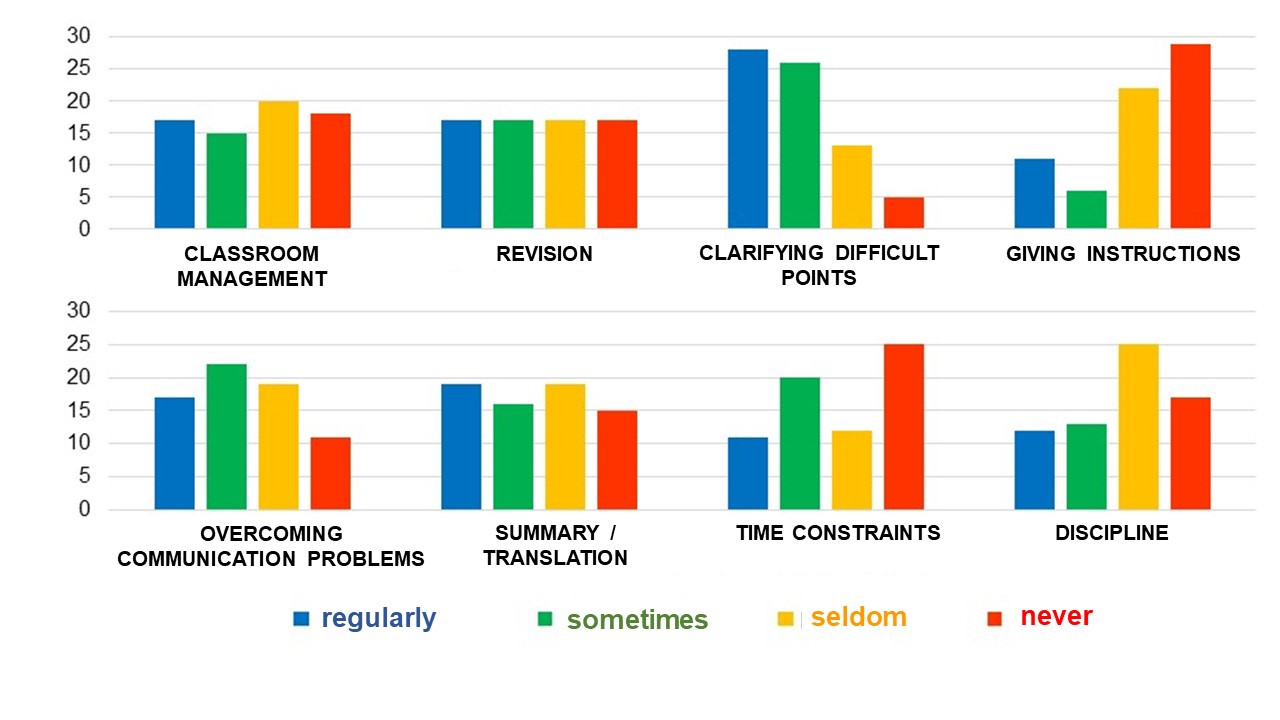

As the students' language and communication skills develop, the proportion of interactions in L2 typically increases in the higher grades; therefore, there is less need to switch to L1. Code switching most often occurs during discussions of more complex topics, which contain several unfamiliar terms and require additional explanations from the subject teacher, or when communication problems need to be resolved (Figure 5). Geography lessons in L2 often require the additional use of Hungarian in specific topics (e.g., the Earth's internal structure, landforms and surface-shaping processes, atmospheric processes,and economic geography), which students may find harder to grasp in Hungarian as well. Due to the more abstract terminology and typical knowledge gaps, more teacher guidance is necessary.

Figure 5. Reasons for Code Switching in Geography Lessons

L1 use is most common when summarizing or translating content, whereas it is much smaller in instructions, often limited to brief task interpretation to support students during classwork or assessments. Although the use of L1 may be triggered by classroom management issues, disciplinary problems, or the lack of time, code switching is typically justified by the linguistic and cognitive challenges associated with learning the subject in L2. Teachers with a higher ratio of L2 use turn to the L1 much less often – and they also tend to do so only when difficult subject content is covered –, while in the case of the others, L1 is present in almost all lesson situations. Although past requirements expected teachers to switch languages in a topic-specific way (e.g., covering the history and geography of Hungary in Hungarian, while discussing the rest of the curriculum mainly in L2), this is no longer typical these days.

Teaching Methods and Resources (RQ3 and RQ4)

Neither now nor in the previous decades has the educational administration considered providing teaching aids for dual language programmes a priority (Federmayer, 2005; Keszei, 2007; Vámos, 2009). Teaching subjects in an L2 requires a specific methodological toolkit, as subject content and language development must be aligned. This is in line with the opinion of most respondents.

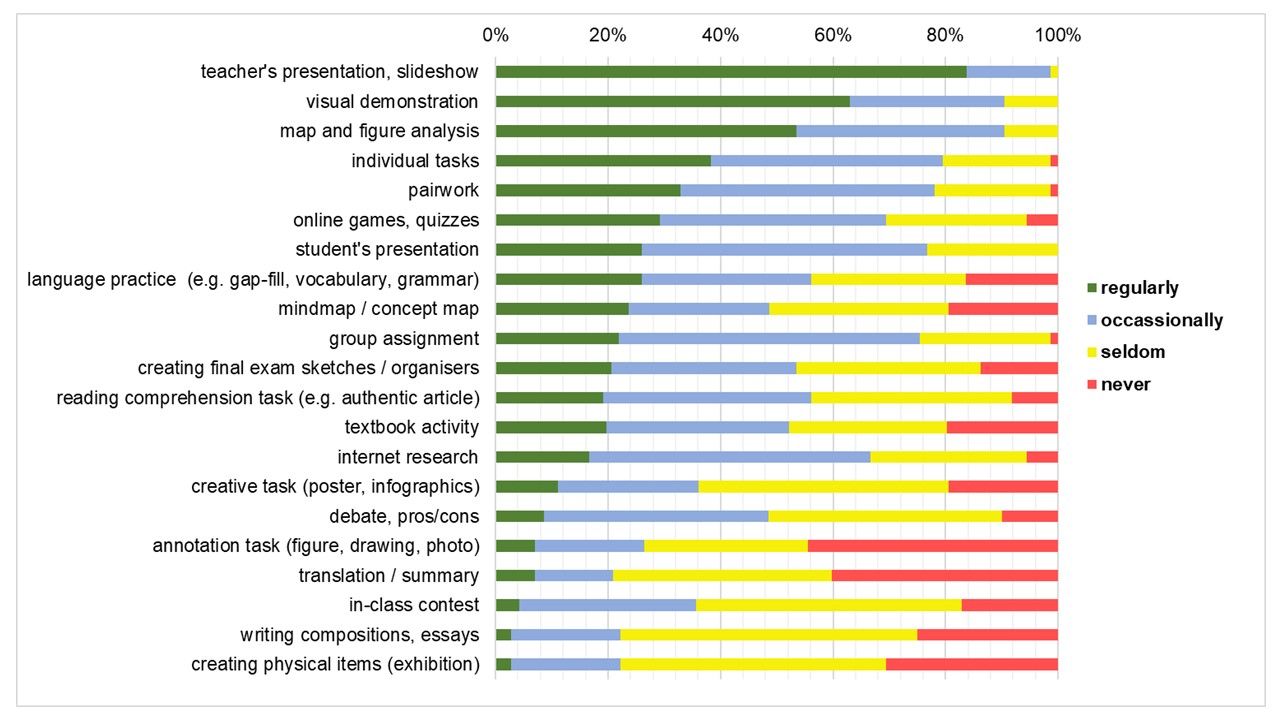

Although teachers seem to rely on a wide array of methods to develop linguistic competence within the context of geographical topics, their practice of teaching Geography in L2 is overwhelmingly slideshow-centered, regardless of language and school type (Figure 6). This is partly a response to the lack of teaching aids that has been a defining feature of dual language education – with the exception of international schools – for decades, and a practical solution for both classroom practice and home learning support. The structure and content of presentations (textual and visual elements, embedded tasks, aesthetic quality) often contribute to the efficiency of teaching, which could be further enhanced by a number of interactive presentation-making online platforms. While the presentation format provides a predictable pathway through topics, it is also extremely flexible as slides can be quickly updated, modified, and rearranged to align with changes in curriculum or timeframe.

Figure 6. Preference and Frequency of Classroom Activities of Respondents

Foreign language textbooks imported from outside Hungary are not – or only partly – applicable for the Hungarian requirements of Geography content. However, certain typical subject content units (such as earthquakes and volcanism, weather patterns, global population, and demographics) can still be aligned, because their structure and terminology show similarity to how those units are presented in Hungarian textbooks. It is essential to note that these resources are typically designed for native speakers of the given language, rather than for bilingual education or CLIL. Textbooks used in international education are also accessible, but they both apply concepts that Hungarian students are not familiar with and require a higher level of language proficiency. Therefore, these resources might serve as inspiration for teachers, but their direct classroom use is very limited. Consequently, textbook-based activities received moderate scores, but the questionnaire did not reveal whether respondents used the books available in the country or the ones they acquired abroad.

Supplementary materials (e.g., a variety of printable resource materials, worksheets, sketches, summaries, and word lists) continue to play a crucial role in L2 subject teaching to counterbalance the lack of textbooks. Practical experience shows that a number of respondents teach using self-developed teaching materials of the same standard as textbooks, designed with a specific focus on interactive tasks (presumably inspired by CLIL pedagogy) rather than the traditional frontal teaching approach.

Language practice (gap-fill, vocabulary,and grammar) and authentic reading comprehension tasks contribute to more specific skill development by using methods familiar to students from general L2 classes, although they are slightly less common. Responses also reveal a widespread practice of in-class collaborative tasks, which demonstrates teachers’ intentions to incorporate elements of CLIL on occasion. As weekly lesson numbers do not support the implementation of a project-based approach, we can assume that those collaborative activities rarely exceed the timeframe of one or two lessons.

In Geography education, the ability to understand and interpret maps and figures is essential – both a subject curriculum and a final exam requirement –, therefore it plays an important role in the teaching practice of the vast majority of respondents. As students are expected to show academic understanding and produce language relevant in the given context, teachers need to develop strategies to help them learn how to communicate about a variety of geographical processes (e.g., greenhouse effect, plate tectonics, demographic transition, migration) and subject-specific figures (e.g., thematic maps, climate charts, population pyramids. Several teachers appear to focus on the visual organisation of content (e.g., mind maps, concept maps, infographics, table organisers), facilitating a more targeted use of cognitive discourse functions and the development of disciplinary literacy.

However, activities requiring greater planning, cognitive effort,a higher level of linguistic demand, and critical thinking (e.g., debate, essay writing) do not tend to fit into the practice of teachers, which may be easily related to several factors discussed above. Final exam sketches are probably the only exception: approximately half of the respondents devote time to this task at least occasionally, but these responses only represent a narrower segment of teachers regularly preparing students for Geography exams, an optional (yet popular) final exam subject choice nationwide.

CLIL Awareness (RQ5)

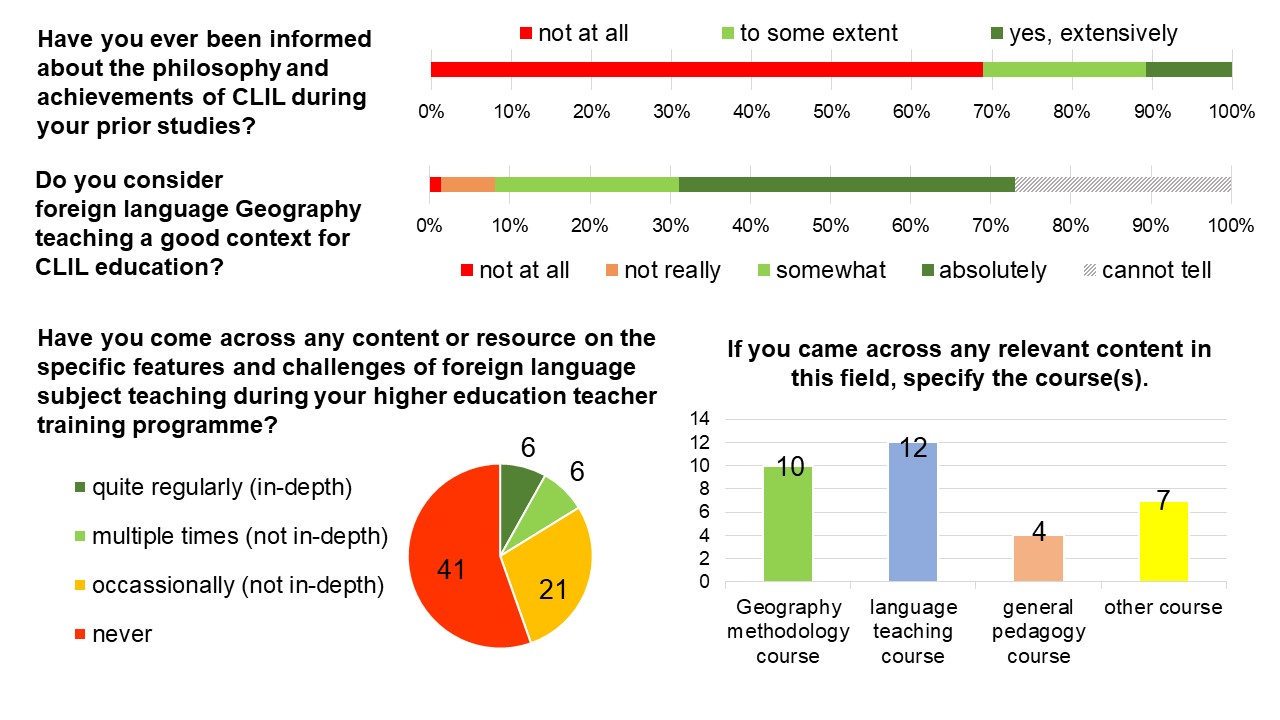

Although CLIL programmes have steadily expanded across Hungary's dual language education over the last two decades, the systematic use and integration of CLIL within school practices and curricula seem to be limited to only a narrow segment of schools and teachers.70% of the respondents did not encounter or study any concepts and methods associated with content and language integration during their higher education studies or teacher training. However, quite a few of them consider Geography lessons an ideal environment for the application of CLIL, implying that they are actually familiar with the phrase (Figure 7), but do not necessarily conceptualise CLIL in their own practice.

Figure 7. CLIL Awareness Among Respondents

This contradiction may be justified by the traditions of teacher training. Most teachers receive formal training in language and subject education separately, in which neither the theory of content and language integration is expected of them, nor its application in classrooms. Teacher training centres do not offer any theoretical or practical training for future teachers to prepare for careers in dual language education, with the exception of a few courses run by two universities, but those are limited to primary and pre-school education. Teachers graduating with degrees in subject teaching and language teaching are expected to be able to teach subjects in foreign languages automatically.

However, subject teachers with a good command of L2 do not automatically become CLIL teachers, hence the demand for the training of in-service teachers to gain the missing knowledge elsewhere, mainly in the form of international courses and workshops offered by training centres (e.g., Erasmus+) or educational-cultural institutions (Goethe Institut,ZfA, Alliance Francaise, Cervantes Institute) across Europe. Due to the steadily widening access to European mobility programmes and job shadowing, teachers often directly look for practical knowledge outside the formal context of teaching training,as ” institutionalised” forms of accredited training courses (listed by the Hungarian Authority of Education) do not offer any meaningful options either. However, the availability of international courses does not make up for the lack of attention to dual language education within local teacher training.

Only a small subgroup of teachers stated that they were properly trained and prepared for foreign language Geography teaching. Their responses indicate that language teaching courses and subject-specific methodology courses were nearly equally relevant in disseminating knowledge about foreign language subject teaching. The majority of respondents did not receive any scaffolding as pre-service or in-service teachers. Teachers’ lack of interest in implementing CLIL in their classrooms can be justified by the fact that their teaching practice has been considered effective without CLIL, and there is no institutional pressure on them to introduce changes.

As seen above in Figure 4, more than half of the respondents report that they spend more than 80% of their classroom interactions in L2, which corresponds to a hard CLIL approach that promotes the use of the target language during lessons, thematic units, or entire courses. Although there are no explicit guidelines or expectations regarding the implementation of any CLIL model in the Hungarian public education framework regulations, CLIL is most often realized in bilingual education. Therefore, it is not surprising that CLIL awareness seems to be higher among teachers working in bilingual schools compared to those teaching in dual language nationality (minority) programmes. This is the result of the conceptual difference between the two types of education.

In nationality programmes, the primary focus is on maintaining and promoting minority cultures and identities through the language. Consequently, the target language is often the mother tongue (L1) of some of the students, and most teachers are also native speakers. Bilingual programmes offer a selection of 3-5 subjects in L2, which is typically a global language spoken by millions worldwide. While several bilingual schools are still selective, filtering students with entrance examinations to ensure that classes have a fairly similar command of L2 (English and German), in nationality schools, students with vastly different backgrounds and language proficiency levels learn together. Nationality programmes are more equipped with traditional printed resources (e.g., translated versions of textbooks and workbooks), but they do not integrate CLIL philosophy, either. (While resource availability and networking among teachers have been traditionally stronger in Germany, other ethnic minority groups are relatively marginalised both linguistically and geographically.)

Discussion

Teacher roles are crucial to achieving the balance between integrating Geography content and L2 teaching, but their success is determined by several interlocking personal, professional, and institutional factors mentioned above. Although the study focuses on five separate research questions, its findings cannot be examined and interpreted independently, as they are closely interconnected in the daily practice of the participants.

Respondents’ dominant perception of being content teachers rather than language teachers seemingly determines not only the content-language ratio but the level of attention they are willing to pay to linguistic skills development (RQ1). Teachers with a more language-driven approach are willing to devote more teaching time to specific language-related issues and apply more L2 teaching methodology within Geography education – both in classroom activities and their own self-designed teaching aids used in class (RQ4). Content-sensitive teachers tend to focus on the development of geographic knowledge and literacy, but provide less room for scaffolding language communication skills (RQ2, RQ4). These assumptions reiterate the findings of previous research papers (Heidari et al., 2022; Morawski & Budke, 2017) on teacher perceptions and the role of L2 in Geography lessons.

The depth of content-language integration shows great variations across the country, regardless of teaching experience, school type, or L2 (RQ2). Consequently, there is no clear evidence that CLIL has become an integral part of foreign language Geography education (RQ5), even though the models of content-language integration have been around for decades (Coyle et al., 2010; Pérez-Cañado, 2011;Vámos & Kovács, 2008). Nevertheless, several teachers with a higher level of CLIL awareness have successfully incorporated certain aspects of these models into their daily teaching practice without studying their theoretical background or receiving any training in the field. We can assume that CLIL pedagogy is implemented in a less deliberate and more instinctive form, depending on teachers’ access to training courses and resource materials (RQ5). Yet, the majority of teachers seem to be satisfied with the ratio of L2 interactions in lessons regardless of the application – or understanding – of CLIL (RQ2).

Teachers clearly recognise the interdisciplinary nature of Geography as a huge benefit in the development of L2 skills, allowing for a diverse range of modalities and classroom activities to be harnessed (RQ1, RQ3). Several respondents have already gone beyond the use of terminology in L2 towards a higher level of academic understanding of Geography content in their lessons (RQ3). This approach necessitates a more conscious integration of subject and language, with a greater focus on subject-specific communication (Bakti, 2023; Coyle & Meyer, 2021; Dalton-Puffer et al., 2024). Teachers’ attempts to diversify their lessons with more interactive methods resonate with the goals of modern language teaching, but while some teachers find the lack of traditional textbooks liberating, others consider it a limitation too difficult to handle (RQ3).

The balanced development of geographical knowledge and language skills requires considerable planning and effort, particularly within the given national curriculum framework and time constraints. As teaching the same subject unit requires more teaching time in L2 than in L1, teachers are often forced to streamline content planned for the school year and, unfortunately, even abandon topics that require more time in L1 as well (RQ1). Although all Geography teachers (regardless of language of instruction) are bound by the same curriculum, the rush to cover as many thematic units as possible may be slowly replaced by a less strict adherence to content – and probably a desire for having more interactive and engaging lessons with a particular emphasis on L2 (RQ4).

As seen above, there are several operational obstacles and deficiencies that hinder teachers working in dual language programmes in general, ranging from inconsistent policy regulations to limited provision of resources and training opportunities (RQ3, RQ5). Previous studies (Vámos, 2009, 2017) reveal that policymakers have not addressed these challenges, leaving them to be counterbalanced by teachers’ efforts at creativity and the development of self-designed materials (RQ3, RQ4).

Conclusion

Geography is a common and popular subject taught in several foreign languages all across Hungarian schools, providing a great amount of teaching experience and expertise to rely on. Responses confirm the pre-survey assumption that Geography teachers have a lot of experiences in common regardless of language of instruction, school type or location. Prior to this study, no attempts have been made to conclude any nationwide subject-specific research on dual language education or CLIL in Hungarian secondary schools.

Despite the relatively wide methodological scope for Geography teaching in L2, aligning subject content teaching goals and language development methods is a major challenge – and only a partial success. Results reflect on teachers’ strategies of overcoming difficulties and inconsistencies, which stem from the lack of attention given to the specific needs of dual language education. A more conscious alignment of content curricula, subject-specific methodology, language teaching, and CLIL pedagogy – combined with adequate organisational support – would empower and enable teachers to more successfully realise content knowledge development in a foreign language context without compromising any subject- or language-related aims of teaching.

Teachers are quite critical of the deficiencies they had to gradually become accustomed to, but they are also able to realise how this situation has contributed to the growth of their mindset and competences (e.g., in teaching materials, ICT expertise, or self-training in CLIL). Since there are hardly any teaching tools developed or adapted for teaching Geography in L2, the resource materials designed by subject teachers are valuable contributions to the field.

Building motivating and engaging learning environments in Geography lessons is crucial at a time when spatial thinking and geographical knowledge are considered less relevant than ever before. At the same time, it has become increasingly difficult to maintain the attention of younger generations on a subject, problem, or task, as the learning process and knowledge acquisition also occur outside of schools and classrooms, in less formal settings where numerous other stimuli are also present. The implementation of the CLIL approach, the use of multiple modalities, and the opportunities offered by digitalisation can all help teachers overcome the difficulties discussed above, even if the emergence of artificial intelligence forces them to change their preferred teaching methods.

While this study aims to explore perceptions of content and language integration in foreign language Geography teaching, its findings reveal a more nuanced picture of dual language educational programs in general, identifying not only their values and achievements but also the institutional challenges they have faced. Findings provide new academic knowledge in the research on the roles of foreign languages and L2 teaching in Geography education, both in the Hungarian and European contexts.

Recommendations

Based on teachers’ survey feedback, the following shortlist of recommendations could be proposed to authority representatives and teacher training centres in connection with Geography teaching in foreign languages.

There is a need for more contact events and knowledge transfer (e.g., teacher training events, workshops, school conferences) where teachers could meet in person, share their experiences, and possibly initiate platforms or projects for future cooperation. As there is currently no organised platform or informal network for Geography teachers working in dual language education, specific networking events or initiatives (e.g., social media groups, regular video conferences, competitions, resource development) should be launched to foster a more active professional community.

There is a clear demand for a more practical and flexible approach in the development and provision of teaching resource materials for dual language schools, with a dedicated focus on content and language integration. Several international examples of such publications are available for study. The educational administration should initiate the formation of thematic resource development groups of experts and teachers for each discipline taught in L2 (including Geography).

Teacher training centres do not provide adequate methodological support for dual language programmes and teacher trainees. If pre-service and in-service teachers do not receive assistance in teaching subjects in L2, they may decide to abandon these programs and pursue other pedagogical challenges instead. This may have serious implications, as dual language education is already facing a shortage of teachers who can cover subjects in L2, threatening the future of certain programs. Specific training courses should be designed, preferably with the participation of practicing teachers from dual language schools.

The unexpectedly large response rate of this survey indicates teachers’ willingness to participate in potential follow-up research activities. In addition, future research in this field could generate more academic interest in the foreign language teaching of other disciplines (e.g., other science subjects) and contribute valuable findings to the European perspective on CLIL studies and bilingualism. Research findings and best practices should be presented at national educational conferences to highlight the achievements and challenges of dual language education for a broader range of stakeholders.

Limitations

It is essential to note that at the outset of this research, there was no existing database of teachers to rely on. Due to the vast differences in the online provision of contact information and the level of enthusiasm shown towards the research by the contacted directors, constructing the database for teachers and schools took more time than expected. However, it still feels incomplete due to the constant fluctuation of the teaching community and the occasional launch or closure of dual-language programs.

Data collection was closed in June 2024, but due to the follow-up networking events (videoconferences, science teacher forums, final exam briefings, and a resource development project), a number of new young teachers have also appeared on the horizon, expanding the professional network of people involved in the teaching of Geography in L2.Additionally, several respondents have since retired, changed schools, or left public education due to personal reasons.

Another limitation was the rejection of a few approached teachers, which can be justified by the fact that Geography teaching in L2 is a narrow research area; therefore, respondents may be identified more easily, even though responses are treated cumulatively and anonymously. Unfortunately, teachers in Hungary are often hesitant to express personal opinions or critical remarks about educational issues and challenges, making it difficult for researchers (or fellow teachers) to persuade them to participate in such surveys – even if those directly address a very specific, previously understudied area of their daily teaching experience.

Even though research into foreign language subject teaching clearly contributes to a deeper understanding of how content and language interaction is realised within dual language classrooms, it may still be considered a relatively narrow niche to investigate.Additionally, regional or international comparisons of findings may not be comprehensive due to differences in educational and institutional contexts.

Ethics Statements

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the University of Debrecen. The participants provided their informed consent to participate in this study.

The author is grateful to all the teachers who participated in this research. Participation was voluntary,and the author provided anonymity to all participants.

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Funding

The research received no institutional funding.

Generative AI Statement

The author did not use any generative AI or AI-supported technologies.