Introduction

The concept of student workload has become central to European university discourse through the implementation of the Bologna Process. Launched in 1999, the Bologna Process aimed to establish and bring coherence to the European Higher Education Area. An important tool used for this purpose has been the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) (Wagenaar, 2020). A key feature of the ECTS credit system is that it is based on the concept of student workload, which in this context refers to the number of hours an average student needs to spend on their studies to achieve the desired learning outcomes. Using student workload as a frame of reference, the ECTS credit system emphasises the notion of student-centred learning. Within the Bologna Process, one ECTS credit is defined as the equivalent of 25–30 hours of student work. A full academic year comprises 60 ECTS credits, comprising around 1,500–1,800 working hours per year for a full-time student (European Commission: Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture, 2015).

However, despite its concise and objective appearance, the concept of student workload has been problematised due to its inherently subjective nature. Notably, Kember (2004) argued that student workload is influenced only partially by the time that students spend studying. This view is supported by other studies, such as Kyndt et al. (2014), who argued that while sufficient time is indeed a precondition for experiencing a manageable workload, qualitative factors also play a significant role. Such reasoning sheds light on how students' experiences of workload are far more complex than merely measuring time.

At the University of Iceland, the Student Council has repeatedly raised concerns about student workload not aligning with the number of ECTS credits allocated to courses, suggesting that students are required to spend excessive time studying in some courses, and calling for this to be investigated (Stúdentaráð Háskóla Íslands, 2022). Students do have a platform through which they can notify officials about excessive workloads in courses: the Teaching and Course Evaluation Survey (TCES). However, the survey does not measure the actual time students spend on a course, as it is not designed to determine whether student workload corresponds to the number of ECTS credits. Instead, survey results reflect students’ valuation of spending time on a course. This example underscores the complexity of the student workload concept. While it clearly can be interpreted, formulated, and applied as a measurement of time students spend studying, it simultaneously reflects students’ perceptions of the very act of spending time studying, and as we will demonstrate, the two do not necessarily coincide. In this article, we therefore argue for a conceptualisation of student workload that sheds light on this complexity.

At the core of this article is a case study conducted at the University of Iceland, focusing on a course in which students had raised complaints about a heavy workload. To better understand these complaints, we began by consulting previous studies that problematise the concept of student workload. While these studies illuminate various complexities, we found them insufficient for capturing the issue in a holistic manner. To address this gap, we turned to theoretical perspectives from posthumanism and actor-network theory (ANT), which have been successfully applied in educational research (e.g., Fenwick & Edwards, 2018; Weaver & Snaza, 2017), though not specifically in relation to student workload. This framework enabled us to explore student workload as something that emerges through relations. In other words, student workload is not a fixed or independent entity, but rather comes into being through sociomaterial entanglements and actions. To fully apprehend the value of this approach, we pose the following research question: How can perspectives from posthumanism and ANT support the conceptualisation of student workload?

Literature Review

Student Workload

Within the Bologna Process, student workload is regarded as a measurable unit of time and is presented as such in international education policy discourses (see European Association for Quality Assurance in Higher Education, 2015). Accordingly, although it has been criticised (e.g., Karseth & Solbrekke, 2016; Kühl, 2014; Souto-Iglesias & Baeza_Romero, 2018), it is embedded in national quality assurance systems across European countries. At the institutional level, the concept is also central. At the University of Iceland, student workload and credits are addressed in various regulations and guidelines. ECTS credits are used to structure study programmes, with courses allocated credits in proportion to their relative weighting (Karjalainen, 2006). Therefore, student workload appears to serve its purpose effectively as a measurable unit of time.

During the formulation of the ECTS credit system, it was acknowledged that actual time spent studying may vary from student to student, depending on individual capacities, prior learning, and learning mode (Wagenaar, 2006, p. 239). The number of hours behind each credit, i.e., 25–30, reflects the expected amount of time that the average student should spend to achieve specified learning outcomes, yet fully acknowledges that a typical student probably does not exist. It also has been acknowledged that actual time spent studying may be influenced by other factors that generally affect the effectiveness of the learning process, such as ‘diversity of traditions, curriculum design and context, coherence of curriculum, teaching and learning methods, methods of assessment and performance, organisation of teaching, ability and diligence of the student, financial support by public or private funds’ (Wagenaar, 2006, p. 243). Thus, variation in student workload was anticipated in relation to both student characteristics and institutional and/or disciplinary traditions. Notably, this argumentation on variation positions student workload as a measurable unit of time. However, variation in student workload can be examined from an entirely different perspective, one that relates to the complex meaning of the concept. Hence, just as student workload concerns time, it also concerns students’ perception of studying.

In 1987, Ramsden argued for a relational perspective that conceptualises the teaching and learning process holistically. He emphasized the importance of studying students’ perceptions of teaching and learning, arguing that students, as individuals, experience their reality differently, which causes them to react differently to their learning environments. Students’ performance depends not only on ability, motivation, and skills, but also on whether the student decides they are needed or not in a particular situation (Ramsden, 1987). In reference to such reasoning, Kember (2004) argued that students’ time spent studying influences perception of workload weakly, although there certainly are limits to how much time students can spend on coursework without feeling undue pressure or becoming overwhelmed with stress. Kember identified several factors that influence students’ perception of workload, such as content, degree of difficulty, student-student relationships, teacher-student relationships, learning approaches, and assessment. Numerous studies have followed similar paths and have identified the same factors that influence students’ perception of workload (e.g., van der Meer et al., 2010; van Herpen et al., 2024; Xerri et al., 2018).

Kyndt et al. (2014) further theorised on perceived workload. Building on Kember’s (2004) pioneering work, they argued that while sufficient time is a precondition for experiencing a manageable workload, more qualitative factors come into play once this quantitative precondition is fulfilled. These qualitative factors can be categorized into three main areas: characteristics of the learning environment, characteristics of the assignment, and personal characteristics (Kyndt et al., 2014). The learning environment encompasses various factors, including course design, student-student interactions, student-teacher relationships, and the teaching process itself. Arguably, the learning environment is the area in which the teacher can exert influence and, to a certain degree, control. Characteristics of the assignment, although vaguely developed, refer to the content and difficulty of the learning tasks organised for students. Finally, personal characteristics encompass attitudes and interests, as well as external factors such as family issues, student employment, and other life circumstances that occur outside the classroom. These characteristics can be collectively described as students’ personal environment, i.e., the factors that encompass each student’s personal characteristics, skills, and knowledge, as well as their social situation and activities.

Building on previous studies, D’Eon and Yasinian (2022) have proposed a new model of student workload that draws upon Newtonian physics. This model distinguishes between student work, course demands, and the load students experience. They acknowledge four different domains: cognitive, physical, social, and psychological, in which student effort is met with course demands. This model further adds to the understanding of student workload as a dynamic concept.

Bringing the student to the forefront, other studies have focused on how students balance their time. Ulriksen and Nejrup (2020) explored students' perceptions of time from a broad and holistic perspective in their ethnographic study of second-year students at a Danish university. Their findings show how students live their lives in different interlinked realms and actively balance and prioritise their time, considering the effort needed, the task’s relevance, and expectations.

This conceptual understanding is also reflected in the Eurostudent report ‘Social and Economic Conditions of Student Life in Europe’, which acknowledged that students make decisions after weighing expected gains and risks, with study programmes’ varying demands and time spent working at paid jobs (Hauschildt et al., 2024; Vögtle& Hámori, 2020). Other studies have further indicated that paid work during studies can affect study performance and perception (e.g., Applegate & Daly, 2006; Bachman & Bachman, 2006; Curtis, 2007;NidogonVišnjić et al., 2024; Toyon, 2023).

As highlighted above, the concept of student workload has undergone significant evolution. Initially centered on time-based measurements, the focus gradually shifted towards students’ perception of time, which enriched the understanding of student workload. Subsequent research on student agency further revealed additional layers of complexity. However, what remains underexplored is the dynamic interplay among the various aspects that constitute student workload. To explore this, we draw on posthumanism and actor-network theory perspectives. This framework enables us to identify, interpret, and articulate the roles, relationships, and agency of diverse elements involved. Below, we outline the theoretical framework that underpins our study.

Posthumanism and Actor-Network Theory

As the term suggests, a posthumanist perspective differs from that of humanism. Rather than attributing agency to humans alone, ‘a posthumanism perspective assumes agency is distributed through dynamic forces of which the human participates, but does not completely intend or control’ (Keeling & Lehman, 2018). Three strands are notable here. First, posthumanism challenges a singular model of the human subject, as it seeks ‘to blur and enliven the boundaries between the human and the nonhuman’ (Lorimer, 2009, p. 344). Second, posthumanism entails the ontological assumption that reality exists through the relations between various elements – whether human or nonhuman, material or immaterial – and their entanglement. Third, within such reasoning, agency is not aligned with human intentionality, nor is it viewed as an attribute of any of the various elements, but rather as a matter of intra-acting between them, creating a dynamic. Thus, from a posthumanism perspective, reality is performative – continuously becoming as it exists only by means of such enactment (Barad, 2003).

Around the turn of the 21st century, posthumanist thought was gaining ground within various disciplines. Similar approaches, albeit labelled differently, were emerging as well, each with its specific preoccupations and tools. However, a common thread entailed decentring the human and emphasising the importance of material relations. One such approach was actor-network theory (ANT), which traces its origins back to the 1980s through studies in science and technology, and the sociology of scientific knowledge, most prominently in the works of Bruno Latour (1987), Michel Callon (1986), and John Law (1986). Its main objective is to shed light on how societal order is realised through the relations among heterogeneous elements, referred to as actants, whether human or nonhuman, in a continually produced web of relations (Latour, 2005). Thus, ANT traces how entities come together, their relations, and their enactment. Furthermore, it critically examines how such networks become stable and durable and are therefore taken for granted and represented as a given entity – or in ANT terminology, ‘black-boxed’.

In educational research and theory, ANT has increasingly been applied. Pioneer in this field is Jan Nespor (1994), who integrated strands from ANT to develop a theoretical language for analyzing the production and use of knowledge. Prominent scholars in this area also include Tara Fenwick and Richard Edwards, who, since 2010, have introduced ANT as a useful approach to educational research (Fenwick & Edwards, 2010, 2014). They have also utilized ANT as a means to examine various settings in the education field (Fenwick et al.,2012) and gathered extant educational studies by different authors who have been inspired by ANT (Fenwick & Edwards, 2012, 2018). Posthumanism similarly entered the territory of educational research around the same time through the work of John Weaver (2010), providing useful insight for various scholars who have continued to explore various educational settings through the lens of posthumanism (e.g., Bustillos Morales & Zarabadi, 2024; Snaza & Weaver, 2015; Taylor & Bayley, 2019).

As previously noted, the dynamic processes underlying student workload remain insufficiently explored. We argue that the relational perspective embedded in posthumanism and ANT offers a valuable lens for identifying the diverse elements that converge within student workload, perceived as a network. Moreover, the notion that agency is distributed across this network allows for a deeper understanding of how student workload emerges; not as a fixed entity, but as a product of interactions among various elements, or actants, both human and non-human, material or non-material, each contributing to its formation through their relations and the agency embedded within. To our knowledge, these approaches have not been used to examine student workload.

Methodology

Setting: University of Iceland and its Students

The University of Iceland is a state-funded, research-oriented institution that offers undergraduate and postgraduate programs across major fields. In the 2023–2024 academic year,approximately 14,000 students were enrolled, including around 8,500undergraduates. Women made up 68% of the student body (Háskóli Íslands, 2024).

Compared to their European peers, higher education students in Iceland are generally older, more likely to have children, and often enter university with substantial work experience. A large proportion (76%) hold paid jobs, compared to 59% in Europe (Hauschildt et al., 2024). These domestic and financial responsibilities likely influence how Icelandic students experience workload.

The University of Iceland adheres to the Bologna guidelines and utilizes the ECTS system to determine the expected duration of study. Programmes are structured by course units, each typically worth 6–10 ECTS credits. A full academic load is 60 ECTS credits per year, with full-time students usually taking three to five courses simultaneously. Grades range from 0–10, with 5.0 a passing grade.

The Case

This research entails a case study on student workload within one single course –Surveys, Interviews and Fieldwork– an eight-ECTS-credit social science methodology course taught to fourth-semester undergraduates in the Department of Geography and Tourism Studies. The number of ECTS credits suggests that students are expected to spend between 200 and 240 hours on the courseduring the semester. The course introduces students to qualitative and quantitative methods and methodologies through a semester-long research project, where they learn to conduct qualitative interviews and surveys, and to combine these methods in their research project. The course is structured into three interconnected phases. The first focuses on the project’s interview phase, the second on the project’s survey phase, and the third on how all these elements intertwine. All coursework supports these phases, and lectures are designed to facilitate students’ project work.

Instruction in the course is characterized by project-based learning (e.g., Guo et al., 2020), providing students with the opportunity to explore real-world problems. This approach is paired with formative assessment, where written and verbal feedback are provided throughout the process. Summative assessment occurs only after students submit the final version of their project report.

The research project accounts for 60% of the final course grade. The remaining 40% is distributed as follows: Two multiple-choice exams administered within the semester collectively contribute 20%; attendance at practical sessions contributes 10%; and weekly reports on time spent on tasks contribute 10%. The weekly reports also serve as a part of the data collected for this study, as described below.

Research Design

The motive for conducting this case study was derived from students’ complaints about the heavy workload in the course. In a TCES conducted at the end of the previous year’s semester, one student remarked that the workload was ‘far too much, considering it was only eight ECTS credits’ and ‘called for constant work, as if it were a 12 ECTS-credit course’. As complaints of this kind prompted the study, it can be defined as action research (e.g., McNiff, 2017), that is, with the intent to examine student workloads in the course as a ‘problem’ and hopefully solve it. Drawing on contemporary knowledge of student workload, which encompasses both a measure of time and a subjective experience, we adopted a mixed-methods design within the action research framework, specifically an explanatory sequential design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2017). This design involves two consecutive phases of data collection and analysis: first, quantitative data to measure the time students spent studying, followed by qualitative data to gain deeper insight into students’ lived experiences of workload. As the analysis of the qualitative data progressed, we gradually gained a deeper understanding of the processes integral to student workload. Rather than sticking to the preplanned methodology, we sought new insight that would allow this new understanding to emerge through our analysis. This insight was gained from posthumanism and ANT, as described above, which helped us conceptualize student workload as becoming. This, in itself – i.e., to investigate what is missed or overlooked in research and listen to the data even if it goes against predefined objectives – is also an effect of posthumanism in research (Weaver & Snaza, 2017).

Participants in the Study

The study involved 46 students who completed the course during the semester of the study’s execution, comprising 31 women and 15 men, aged 21 to 47, with 75% falling between 21 and 26 years old(average age: 25.56). All were enrolled full-time. Of the 46 students, 39 provided information about their housing and family status; 16 lived with parents and 23 lived independently, mostly in rented housing. Five students had two children each, while others had none. Among the 40 students who reported employment, 32 (nearly 70%) held paid jobs working between four and 30 hours weekly, with an average of 14.58 hours, roughly equivalent to 10 ECTS credits.

As a case study, the research draws on four data sources: weekly reports, attendance lists, qualitative interviews, and TCES, detailed in the following section.

Data Collection and Analysis of Data

Weekly reports: Every week, students submitted a report detailing the time spent on course-related tasks. The report was an Excel spreadsheet with predefined weekly forms, listing various tasks that the student could have performed outside the classroom. Each student received a personal document via Microsoft OneDrive, allowing both the student and the teacher (also a researcher) to access it. This setup enabled the teacher to monitor completion and send reminders when needed.

Students were divided into two equally large groups: one reported during the first and third phases of the course, while the other reported during the second and third phases. Thus, each student submitted a weekly report for two-thirds of the 19-week semester, which included Easter break and the exam period. These reports counted for 10% of the final grade and were intended to encourage student participation in data collection. Students were urged to report honestly, withafull grade awarded simply for completing the form, regardless of the time reported.

Attendance lists. To measure classroom time, attendance was recorded for both lectures and practical sessions throughout the semester. These records, along with weekly reports, were compiled into a single Excel spreadsheet and analysed using descriptive statistics. The results are presented in the first section of the findings.

Qualitative interviews:To gain an understanding of their experiences studying within the course, six students, three from each group, were selected to be interviewed. The selection was based on the amount of time students had spent studying, as revealed in the weekly reports and attendance lists, categorized as low, medium, or extensive. To avoid selection bias, students were randomly selected within each category, while maintaining the gender ratio. The final sample included two male and four female students, reflecting the overall gender distribution in the course. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity of the interviewees, they were assigned pseudonyms in the presentation of the findings: Helgi and Arni (males) and Sonja, Anna, Hulda,and Svala (females).

The interviews were conducted as semi-structured qualitative interviews (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2018), utilizing an interview guide to ensure that specific aspects were discussed during each interview. However, the emphasis was placed on maintaining a natural and conversational flow throughout the interview, in which students were given the freedom to express their thoughts.

Conducting research with one’s own students raises ethical concerns, particularly the power relations that arguably exist between students and their teacher (e.g., Fedoruk, 2017). In this study, students could hardly be expected to speak freely to the teacher about their experiences within the course, as the teacher would later grade their assignments. Data generated under such circumstances inevitably could be deemed less valuable. To mitigate this, interviews were conducted only by one of the authors,who had no prior connection to the course. Recordings were concealed until students had received their final grades. Before each interview, this procedure was discussed with the participants, who also received a signed statement outlining the process.

The interviews were analysed using grounded theory methods (Strauss & Corbin, 1996). First, open coding was employed to identify initial concepts within the data. This phase was conducted independently by the two researchers to ensure unbiased identification. Next, axial coding was applied collaboratively through dialogue to organize the concepts into coherent categories and subcategories. Finally, selective coding was used to refine central themes, providing a structured framework for interpretation. The analysis of the interviews and other data revealed some discrepancies between time and perception, confirming existing knowledge on student workload (Kember, 2004; Kyndt et al., 2014). However, our findings also suggested a complex interplay between various elements, which collectively affected both the time spent studying and the perception of studying. In an attempt to capture this complexity, we adopted an ANT perspective that allowed us to trace the various agential elements that comprise student workload. Notably, our study did not begin as an ANT study, which aims to follow the actants. This approach, however, helped to enhance our understanding of the data. The results of this analysis are presented in the findings as factors of student workload that contribute to its development.

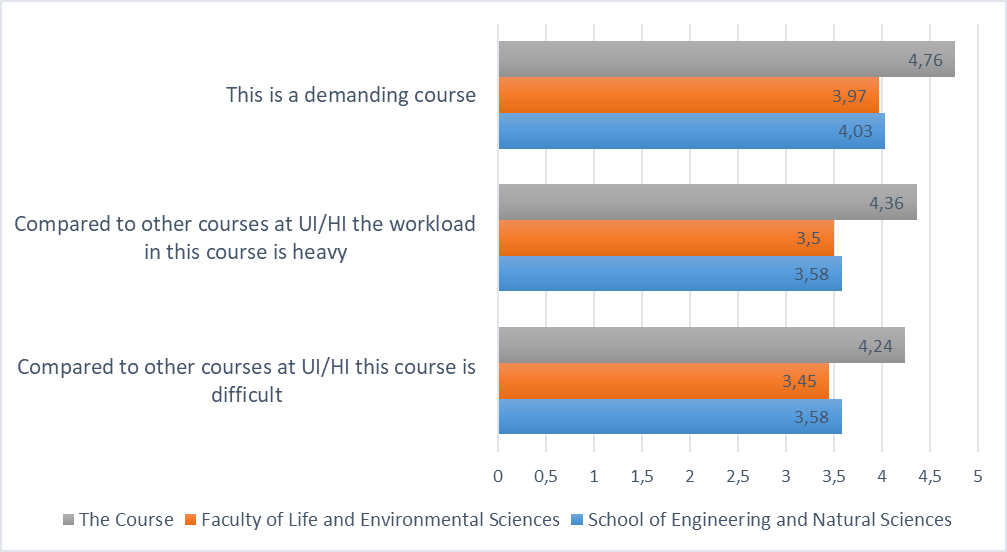

Teaching and Course Evaluation Survey. The TCES, conducted at the end of the semester, provided additional insight into students’ workload experiences. It includes 22 questions across six categories, with three workload-related items probing students’ subjective view: whether the course is demanding, difficult, or heavier than others. Results show overall and mean ratings for each category and question, with comparison to other courses within the faculty and school. Two open-ended questions invite comments on teaching and study conditions. The survey results were compared with recorded measurements of the time students spent on the workload, as well as with selected themes derived from the interview analysis. These comparisons are presented in Section 2 of the findings.

Findings

In this section, we describe and discuss the results from our analysis. Prompted by students’ reports of a heavy workload in the TCES, our point of departure was to investigate how much time students spend studying for the course. These time measurement results are presented in the first section. The second section focuses on students’ perceptions of their workload as expressed in the TCES, as well as in the qualitative interviews. The third section draws on the theoretical framework by examining various actants at play as the student workload is created, within both the learning environment and the students’ personal environment. The fourth and final section further explores student agency within the student workload network.

Time Measurements

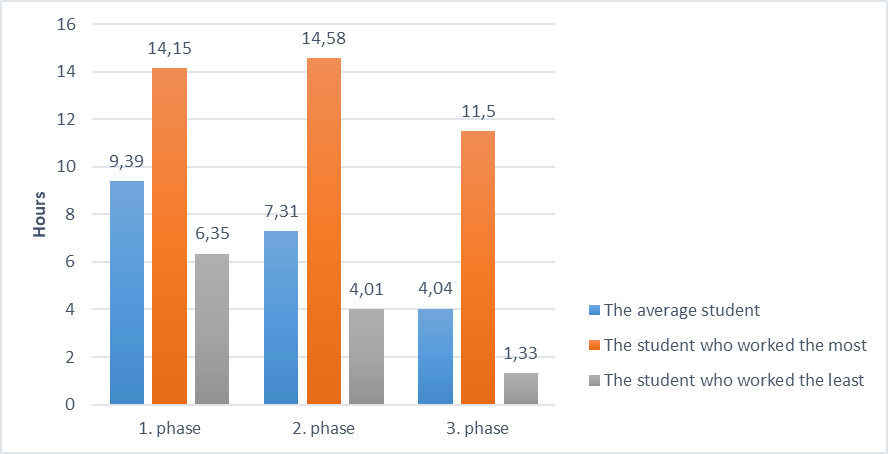

Based on the data collected in the weekly reports, students spent an average of 7.5 hours per week on coursework – considerably lower than what could be expected for an eight-ECTS-credit course – or only 57–71% of the ECTS criterion. However, students’ efforts varied significantly, both between individuals and across different phases of the course, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Variance in Time That Students Spent on Course Work During the Course’s Three Phases

Notably, the topic of the first phase – qualitative interviews – was relatively new to all students, which may explain the higher average number of hours spent. During the second phase – statistics – all students had some prior knowledge. In the third and final phase, students were primarily working on revisions to their project based on the teacher’s feedback. The considerably lower number of hours may be explained by the fact that they were not engaging with new materials or methods.

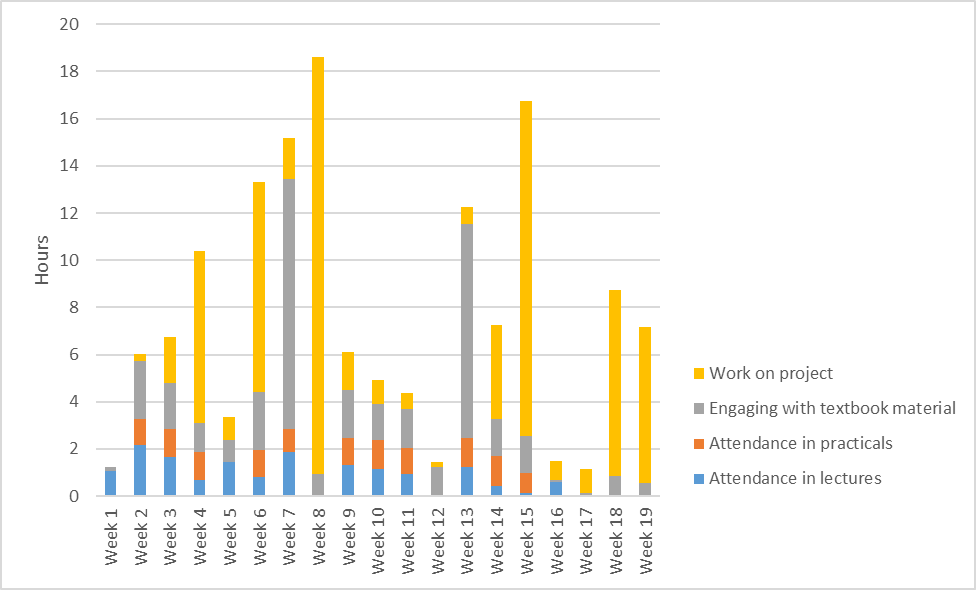

A more detailed explanation of the data in Figure 2 reveals how time was spent on course activities each week.

Figure 2. Profile of Average Student Workload in the Course by Weeks and Learning Activities

Figure 2 indicates that the workload was uneven and influenced by various learning tasks organised throughout the course. For example, in Weeks 7 and 13, students read the textbook in preparation for an exam scheduled that week. In Weeks 8 and 15, students focused on writing up the results of their research project for a report due that week. The low activity in Weeks 16 and 17 can be attributed to the spring exam period, during which students likely devoted their time to preparing for final assessments in other courses. Furthermore, Figure 2illustrates how curriculum design influences the student workload pattern, emphasizing the teacher’s agency as a curriculum designer. However, the pattern can also be interpreted as a reflection of students’ prioritisation of their time. This example underscores the relational aspect of the educational setting.

Students’ Perception of Workload

Although the time spent on coursework was considerably lower than the ECTS criterion suggests, students’ perception of a heavy workload was clearly expressed in the TCES. Compared with other courses they had taken, students reported that the workload in this course was by far the heaviest, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Teaching and Course Evaluation Survey results

Although the results from the TCES might give the impression that the course workload was excessive and possibly unfair, the interview data offer a fuller understanding. A general feeling among students was that the workload was indeed considerable, but not too heavy. Helgi voiced a common view:

Even though many say it is a difficult course with a heavy workload, I think it is well-organised. The instructions are so clear that learning should not be that difficult. But it takes time!

Although the coursework was viewed as time-consuming, students reported that the workload was fair, with this fairness primarily attributed to the formative assessment. Students recognised that,due to the practical nature of the topic, hands-on experience was necessary. Some stated that the assignments were both rewarding and enjoyable, as Svala noted:

It was a good experience to have the opportunity to do this all by yourself. You learn much more this way compared to traditional lectures.

However, the course organisation, which emphasised formative feedback, required students’ consistent attention. This may have induced a sense of a heavy workload, as oneparticipant noted: ‘Your mind is always on this course.’This could explain why some students felt they needed to prioritise this course regularly throughout the semester. Some also viewed this as an advantage, as it helped them manage procrastination tendencies, as was the case for Arni:

You are sort of forced to work constantly on it. Like in the qualitative part, you only had a week to prepare, to find an interviewee, and then you just had to do it. You couldn´t postpone it. ... This suited me well. If I had had more time, I would have postponed it.

The mismatch between the time measurements and the TCES results is noteworthy, confirming that a heavy workload is not determined by time alone. As revealed by the interview data, the heavy workload in this course was not experienced negatively, but could be attributed to various factors considered important by students.

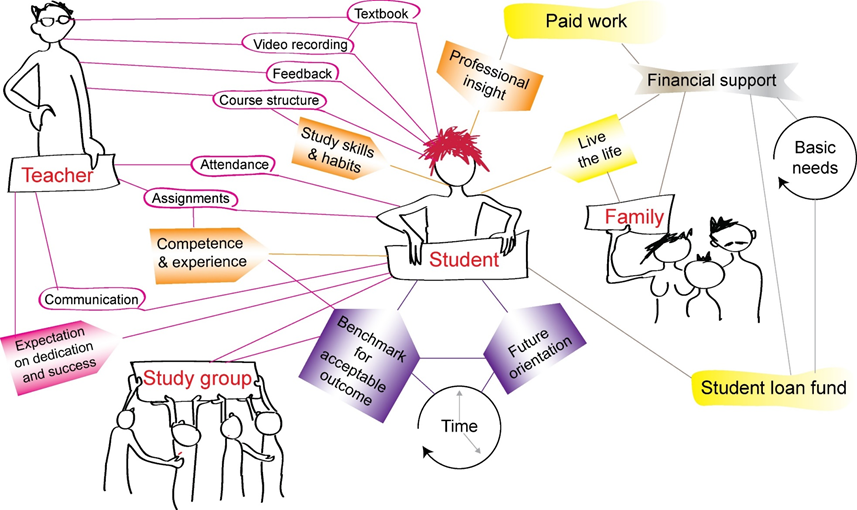

Student Workload as Network: Actants in Student Workload

Further analysis of the interview data revealed that student workload is shaped not only by time and perception but by the dynamic interplay of multiple elements. Building on the theoretical framework, we identified actants that arguably constitute student workload. These are depicted in Figure 4. In the following section, we discuss these in terms of the learning environment and the personal environment.

Figure 4. Actants Within the Student Workload

The Learning Environment. An important human actant in the student workload network is the teacher, who plays an active role in creating the learning environment within the course. During the interviews, the students referred to several elements of the course that they believed influenced their workload and learning behavior, such as the course structure, textbook, access to video recordings, assignments, and feedback, as well as general communication with the teacher. These actants are depicted on the left side of Figure 4.

Many of the interviewees explained how the formative assessment influenced their use of time, revealing “study skills and habits” (see Figure 4). It helped keep them on track, working against self-acknowledged procrastination, a study habit that Helgi described as ‘the nature of students’. Postponing the reading of course texts until the final test appeared to be a common habit. Hulda explained her perspective this way:

I thought the course structure was great. It is not like you have to do everything at the last moment; rather, the assignments are distributed, which was excellent. It really worked well for me because I work best under pressure. So, it suits me much better if there are many small pressure points, rather than a big one.

The course structure requires students to take time to reflect on assessment feedback. When asked whether this was time-consuming, Anna said:

Yes, but I still like it. As a university student, I think it is important for what I am doing. It is frustrating to turn in a paper, receive a 7 as a grade, and have no idea why. So, no matter which grade I end up receiving, acting on the feedback gives me a deeper understanding of why and how I have to improve my work.

Anna’s quote demonstrates that even though formative assessment requires more time from students, she perceives it as meaningful and contributing to a positive learning experience.

The course content was provided through a textbook and lectures, which were also videotaped and made accessible to students afterwards. As the textbook is in English, students’ “competence and experiences” (see figure 4) influenced the time required for learning. For example, Hulda described herself as a strong student due to her proficiency in English and her ability to read quickly, while Sonja reported struggling with English texts. Svala described reading as time-consuming, as she has dyslexia.

Students appreciated the video recordings immensely. While some said they used them to review material and deepen their understanding, either after class or when preparing for exams, others used them as a substitute when they missed class. The interviews also revealed different study approaches to using the recordings. While Svala listens attentively and takes notes, Sonja explained that she browses through them in search of key points. This demonstrates both different study habits and variations in the time spent studying.

Course assignments require different skills. During the qualitative phase of the course, students were tasked with conducting interviews and transcribing them. For introverted students, the interviews proved to be a daunting task, while others welcomed the challenge. All interviewees found transcription to be time-consuming, though some had better typing skills than others, which helped save time. During the quantitative phase of the course, students with a solid foundation in statistics spent less time on their assignments than those with less experience.

Within the learning environment, fellow students also played an important role in the actualisation of student workload. Several students belonged to “study groups” (see figure 4) that provided support in various ways. For example, Hulda explained how sharing tasks within a study group lightened her workload while simultaneously deepening her learning:

We always write notes for the tests together and combine our notes, and coach each other. This has helped me through a lot of tests. Just talking and explaining to each other helps.

Thus, sharing learning efforts within a study group is considered a productive use of time.

The Personal Environment. In the previous section, we discussed the student engagement within the learning environment. In this section, we focus on activities that occur outside the formal learning environment, as described by our interviewees when explaining how they use their time. These are depicted on the right side of Figure 4. Many interviewees stressed the importance of ‘living the life’, referring to activities taking place with friends and family. These activities must be balanced against the time needed for studies, as Svala explained:

I have decided that even if I only receive 6 on this particular exam, because I decided to take a walk with my mother instead of spending two more hours studying, that is what I will do.

The activity outside the school environment most frequently discussed during the interviews was students’ time spent at “paid work” (see Figure 4). All interviewees held a paid job in addition to their studies. Their working hours varied, from a moderate 16 hours per month to nearly full-time positions, exceeding 30 hours per week. When discussing their work experiences, three main elements emerged as crucial: work as a way of contextualising the subject, the flexibility offered by the job, and the actual number of hours spent working.

Participants found themselves in various financial situations. Some still lived at home, while others needed to finance their “basic needs” (see figure 4), such as paying rent, as Anna explained it:

There is a reason for my working alongside my studies, and it is that I do not have a family here, so I have to rent. So, I need money, and LÍN [the Icelandic student loan fund] doesn’t offer me a study loan, as my wages are above the limit. And I work because I don´t get the loan. So, this has become a vicious cycle.

Although student work is generally acknowledged as a common part of student life, students are aware of some teachers’ negative attitude toward it. Anna referred to a message she received from a teacher, stating: ‘Students are not expected to work along with their studies’. She found this attitude unfair, as she relies on her wages to meet basic needs.

Interviewees did not express that their jobs interfered with their studies. Hulda, who works at a tourist information centre every other weekend, believes she could even work more without it affecting her studies. However, increasing her working hours would make it more difficult for her to go to the gym, an activity she is keen to continue. This example highlights the interplay between different actants within the student workload network.

Arni works at a hotel, mainly on night shifts, putting in 12-hour shifts and sometimes working up to 50 hours per week. He is granted a certain degree of flexibility when the study load is great, but admits that heavy working weeks have interfered with his study time. Nevertheless, working also offers benefits, as it requires him to organise his time more effectively:

OK, as long as it is not a crazy number of hours, I don’t think it is worse to keep a job. You know it has kind of helped me to be more organised. ... Rather than having the whole day to study, I had to think: OK, I am going to be working this period for this many hours, and then I only have this time to study.

However, as working hours increase, it becomes more difficult to juggle work and study time. Some participants emphasised the flexibility they receive in their paid work, where consideration is given to demanding periods and heavy workloads in their studies. Shifts can be rescheduled, working hours reduced, and extra hours saved for times when more study time is needed. Yet, when working hours become too demanding, flexibility is no longer available, and students lose control over their schedules.

Most of our working participants hold a job somewhat related to tourism, as it is the largest industry in Iceland and requires a large workforce. Thus, the participants appear to utilize their paid work experience as a means to provide context for their studies when they become overly abstract at times.

Hulda, who works at an information centre for tourists, appreciates the insight her work provides into studies:

You see, I really like pondering over what type of tourists visit the centre. We were learning about different categories of tourists, and I like to hypothesize whether this one is like this or that type of tourist.

However, Helgi works at sea during the fishing season in the spring and said his paid job does not provide him with much experience in tourism:

I have a very unclear idea about what that means to work within the tourist enterprise, what the industry looks like, and what is going on within it. But that can naturally be explained by the fact that I do not hold a paid job in the field.

As can be seen, students’ paid work can provide them with “professional insight” (see Figure 4) into their field of study. Thus, although paid work here is viewed as belonging to their personal environment, it is strongly tied to their disciplinary learning.

Student Agency Within the Workload Network

In the previous section, quotes from students hinted at their agency in managing their time. Far from being passive receivers of schoolwork imposed upon them, the students revealed how they consciously made decisions about how to allocate their time. The conscious decision-making appeared to be based primarily on two distinct ideas that we identify as actants in the student workload network:“Benchmark for acceptable outcome” serves to regulate time that students have available to manage their lives, including their studies, whereas “Future orientation” –whether within their current studies, future education or the professional field – refers to student’s evaluation of the relevance of the learning outcome within a particular course. If the course aligns with their future orientations, whether short- or long-term, students are more likely to experience that the time spent on their studies is well-invested. This perception, in turn, can influencethe amount of time they dedicate to studying (see Figure4). Studentsgenerally described their acceptable outcome as a certain grade. For example, Helgi, after joining a study group, found himself more ambitious this semester, purportedly raising the bar in this regard:

This is the first time I’ve thought, ‘Now I want to get 9 and above, not just 8,’ because I have generally received 8 throughout secondary school, and now in university, I have had an average grade of 8.

Helgi seems to perceive a correlation between time spent studying and the grades he receives. This sense of correlation was also evident among other students. For example, Anna, when asked whether she observed a link between the time spent studying and the grades she receives, replied:

Possibly, yes. I think it depends on the individual. For example, I am just quick to take in the study material. I only need to be told something once, and then I remember it. While others might have to hear it a couple of times. But on the other hand, I think that if I were to read every single word and attend every single class, and then review it, if I were to do all that we are told to do, I might possibly be getting 8 and 9 in every course, rather than 7 and 8.

When asked whether a higher grade was important to her, she replied:

No, I think it's good to have 7 or 8. Of course, I wouldn’t mind having 9 and 10 in everything, but it doesn’t bother me. But on the other hand, I would mind going below 7. I feel that 7 is my baseline.

Anna’s interview revealed that her study experience over the years had taught her the extent to which she needs to be committed. This was supported by the weekly reports during the semester. On average, she dedicated a little more than six hours per week to coursework outside the classroom. As for class attendance, she was present for six lectures out of 18 and eight practicals out of 10. In contrast, Helgi attended 15 lectures and nine practicals. Interestingly, Anna’s final score in the course was 8, whereas Helgi’s was 9.

Discussion

In this study, we set out to explore dynamics at play within student workload with the theoretical input from posthumanism and ANT, and to fully apprehend the value of this approach, we posed the following research question: How can perspectives from posthumanism and ANT support the conceptualisation of student workload?

This theoretical framework guided us to view student workload from a relational perspective, as a network of diverse actants through which agency is produced, creating a dynamic system. As demonstrated in our findings, this approach enabled us to identify a variety of actants, many of which have previously been identified and discussed in other studies as important factors for student experiences of workload, such as course design, teacher-student relationship, course demands, and student employment (D’Eon & Yasinian, 2022; Kember, 2004; Kyndt et al., 2014) However, this approach has furthermore revealed the dynamic interplay between these actants – an interplay that is brought into existence by their relations that is constantly evolving and changing in order to exist. Therefore, student workload does not pre-exist in itself. Drawing on terminology from our theoretical framework (Barad, 2003), we thus argue that student workload is performative and constantly becoming.

Without undermining the importance of the agency that emerges from the relations between the various actants identified in the study, our findings underscore the agency of the student within the student workload network. Despite the flat ontology and distributed agency typically assumed in actor-network theory, human intentionality can not be overlooked. Although this introduces some conceptual tension between our findings and the theoretical framework, we found this aspect of ANT to be valuable for our analysis, as it helped us move beyond an exclusive focus on human agency. Our findings suggest that the student occupies a central role among the various actants within the network and is therefore fundamental to the emergence of student workload (see Figure 4). Students make conscious decisions about how to allocate time for their studies, as well as for other aspects of their lives. Rather than being a passive recipient of workload imposed upon them, they are active agents in shaping their own workloads. Moreover, students are not merely learners; they lead complex lives in relations with several actants that, although external to the formal learning environment, are integral to the student workload network. From a posthumanism perspective, this underscores the wholeness of the student, an individual whose life encompasses family, friends, employment, and social and leisure activities.

Time is a limited resource, so allocation needs to be considered carefully. In relation to student agency, our findings revealed actants that play a significant role in student decision-making processes, regarding how they allocate time to their studies. These we term as “Benchmark for acceptable outcome” and “Future orientation”. Although these concepts are not new in themselves, to our knowledge, they have not been central to theoretical discussions about student workload. Indeed, the agency of the student in relation to workload has, with few exceptions, rarely been the focus of study (see Ulriksen & Nejrup,2020).

To sum up and respond to the research question: Posthumanism and ANT offer a holistic framework for understanding student workload, not only as a network of relational actants, but also by acknowledging the student as a complex being embedded in multiple sociomaterial contexts. This approach enables an analysis of the dynamic interplay between actants, counteracting the common black-boxing of student workload and revealing its ongoing process of becoming. Our findings, generated through this framework, challenge several common and often unconscious preconceptions about student workload, including: viewing students merely as learners; assuming homogeneity in student thinking and behavior; placing overconfidence in time-based measurements; and interpreting student employment solely as a negative influence on academic engagement.

Our take on student workload also challenges the often-presumed notion that teachers bear the primary responsibility for student workload through course design. Teachers are certainly one of theactors of thestudent workload network. For example, our study reveals how certain course structures can work against student procrastination, and how clear instructions and feedback, as well as access to teacher feedback, can save students time and effort, thereby contributing to positive experiences with workload. Kyndt et al. (2014) emphasized the important role of teachers within the learning environment. Other educational scholars have emphasised elements in course design that contribute to successful learning (Ramsden, 1987) and student-teacher relations (Felten&Lambert, 2020). However, by foregrounding student agency and the complexity of student workload, this study contributes to a more nuanced and inclusive understanding of student workload.

Conclusion

This study was derived from the results of the TCES, which asked students whether their course workload was demanding, difficult, or heavy. The phrasing of these questions reflects how, within university discourse, student workload is often framed in negative terms. However, our study revealed a more nuanced picture: although TCES results show that students evaluated the course workload as demanding, difficult, and heavy, they neither spent the amount of time typically expected for the corresponding ECTS credits, nor did they perceive the workload negatively. This prompted further analysis of the data through the lens of Posthumanism and ANT. By employing this theoretical framework, we aimed to capture the dynamic interplay that constitutes student workload, while simultaneously exploring the analytical potential of Posthumanism and ANT. Through our study, we conceptualise student workload as performative and becoming; it is brought into existence through sociomaterial entanglements among various actants, both human and non-human, material and non-material, whose relations are constantly evolving. Within this network, the student holds a central role, bringing workload into existence through actions shaped by decision-making, grounded in their relations to other actants that co-constitute the student workload network. Our study thus offers a new conceptualisation of student workload – one that may carry implications for how universities design, evaluate, and support student learning experiences, while also informing future research on educational practices through a more relational lens.

Recommendations

Following up on our conclusion, our recommendations fall into two categories: on the one hand, suggestions for implementing the model within higher education institutions; on the other hand, directions for how our findings can serve as a foundation for further research.

Focusing on the University of Iceland, our findings offer valuable insights for both educational support services for teachers and administrators, as well as the institutional quality assurance system. Currently, educational guidelines and advisory materials primarily emphasize time-based measurements of student workload. Teachers are provided with a model that helps them calculate the number of hours required for various tasks and activities. Drawing on our study, we suggest that these guidelines be expanded to reflect a broader understanding of student workload. Such an approach would enable teachers to better recognize the possibilities and constraints involved in organising student workload, moving beyond a purely quantitative framework. Regarding the quality assurance system, we recommend revising the TCES to incorporate a more in-depth and nuanced understanding of student workload. This would enhance the system’s capacity to support meaningful evaluation and continuous improvement in teaching and learning practices.

More broadly, our findings contribute to the ongoing discourse on student-centered approaches in higher education. We argue that, just as agency is distributed among the various actants within the student workload network, so too is responsibility. Our results can serve as a valuable tool for facilitating dialogue with students about their own agency and responsibility within this network. By engaging students in discussions about how their workload is shaped, and how they, in turn, shape it, educators and student support staff can foster a more participatory and reflective learning environment.

As our study is a small-scale case study within a specific context, it opens up opportunities for further exploration across diverse educational settings. It would be valuable to investigate whether the actants are present in other contexts and whether additional actants emerge that play a significant role there. Such studies could build upon the theoretical framework presented here, employing methodologies commonly used in ANT research. In our study, we identified various actants within the student workload network, some of which are novel contributions to the discourse, such as the „benchmark for acceptable outcome“ and „future orientation“. Further research into these actants would deepen our understanding of their agency and significance within the broader student workload network, potentially enriching both theory and practice.

Limitations

The conceptual model here created builds on a small case study. However, we utilized four different types of data, namely weekly reports, attendance lists, qualitative interviews, and TCES, which provided multiple perspectives from students. The number of interviewees was limited to six students. Including more interviewees within the sample could have provided richer results. Still, the interviewees were purposefully selected to provide a broad spectrum of students’ experiences.

Ethics Statements

Participants provided written informed consent to participate in the study and to have their findings published.

This research would not have taken place without the students participating in the study. We are most grateful for their generous input. We would also like to extend our gratitude to our colleague, Sigurbjörg Jóhannesdóttir, who graciously illustrated our model. Finally, we thank the various colleagues who have provided us with feedback on multiple occasions, both nationally and internationally, when we have presented our findings.

Generative AI Statement

As the authors of this work, we hereby declare that we did not use any AI tool in conducting this research. We, as the authors, take full responsibility for the content of our published work.

Authorship Contribution Statement

Waage and Geirsdóttir contributed equally to this study: Waage: Conceptualisation, design, data collection, analysis, writing. Geirsdóttir: Conceptualisation, design, data collection, analysis, writing.